Nato and Russia - in search of dialogue

- Published

Nato forces held their largest-ever exercise since the Cold War in Poland in June

"Nato and Russia, based on an enduring political commitment undertaken at the highest political level, will build together a lasting and inclusive peace in the Euro-Atlantic area."

So read the Nato-Russia Founding Act, signed in Paris in May 1997.

This document - with the Cold War over and the Soviet Union gone - was to have been the start of a new, more constructive relationship.

"Nato and Russia," it went on, "do not consider each other as adversaries."

Well, how things have changed! While tensions are clearly not at the level of those at the height of the Cold War, they are rising.

Crying foul

Russia's seizure of the Crimea has, in the oft-repeated words of Nato leaders, torn up the play book for security in post-Cold War Europe.

Paul Adams: Why Russia is set to dominate the Nato summit

Last week's Nato Summit in Warsaw began the process of sending military reinforcements eastwards, both to reassure worried allies like Poland and the Baltic states, and to send a signal to Moscow that the Alliance would defend the territory of all of its members.

Russia is already crying foul, with Moscow's envoy to Nato Alexander Grushko insisting earlier this week that such troop movements contradict the provisions of the Founding Act.

So Nato and Russia have a lot to talk about on Wednesday In Brussels. Indeed the body that is meeting - the Nato-Russia Council founded in 2002 - was itself a product of the optimism of those early days of Nato-Russia harmony.

'Original sin'

It is not just Ukraine though that has soured the relationship.

There was Russia's war with Georgia that in many ways began the rot. And there was the US decision, backed by Nato, to build limited ballistic missile defences in Europe which Moscow insists upon seeing as a precursor to a wider system that could undermine the credibility of its own nuclear deterrent.

Navy video captures Russian flyby in mid-April

But Nato's "original sin", as far as Moscow is concerned, was the broader policy of Nato expansion, taking in states such as the Baltic nations whose territory used to be part of the Soviet Union or Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia which used to be among Moscow's Warsaw Pact allies.

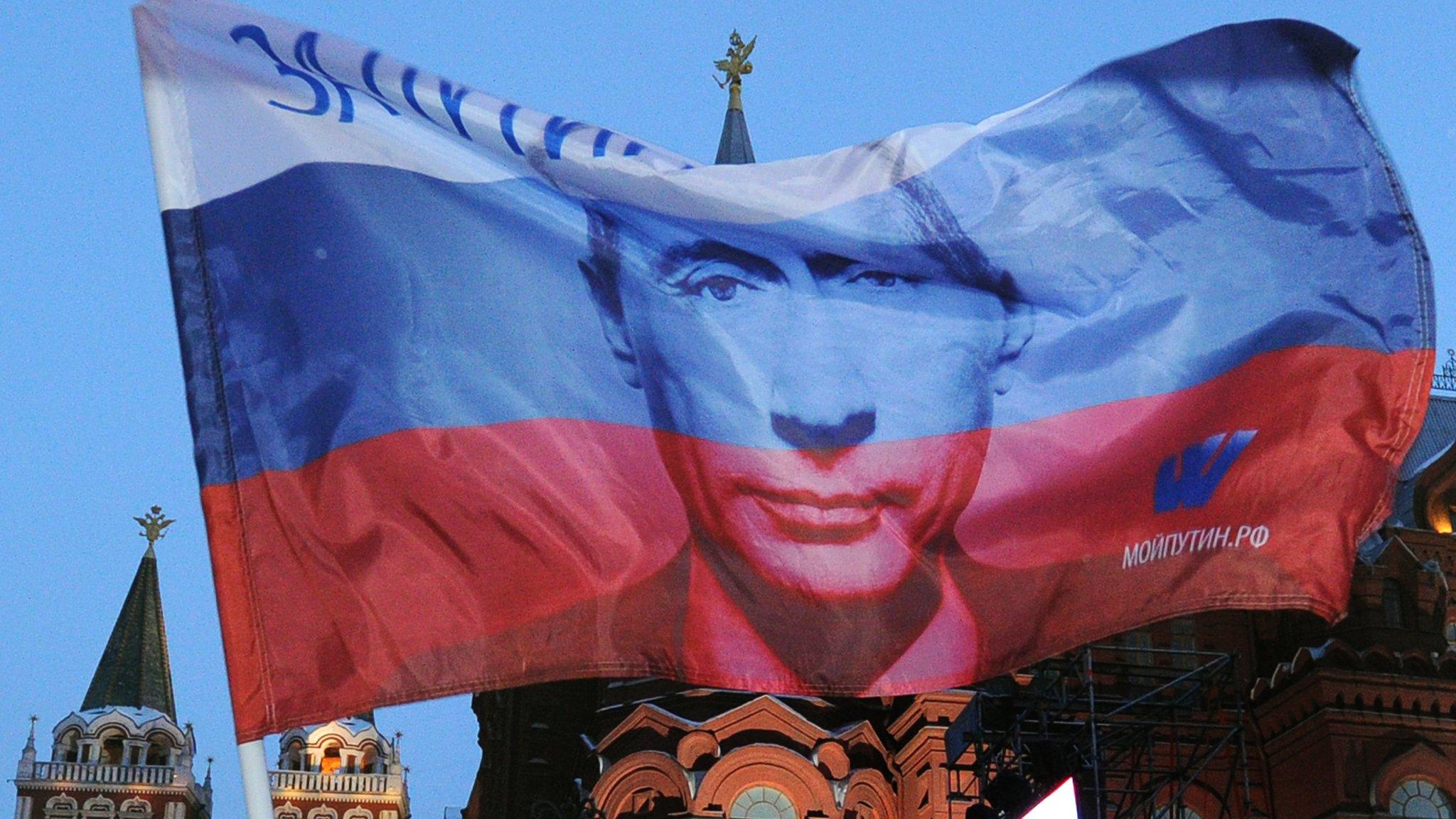

Nato now wants to explain its new military deployments to Moscow. It will stress that for now these are small-scale, but more deployments will likely follow unless Russian President Vladimir Putin changes tack.

Unpredictable Russia

Nato would prefer dialogue and partnership with Moscow. But it cannot accept Russia's use of force in Ukraine.

It is alarmed too at what it sees as a pattern of irresponsible behaviour on the part of Russian aircraft over the Baltic region and elsewhere, which routinely fly in busy air space with their transponders - or identification beacons - turned off.

Nato cannot accept Russia's use of force in Crimea

If Russia does not like the pattern of stepped-up Nato military exercises established in the wake of the seizure of the Crimea, Nato is alarmed by a whole series of Russian exercises, held at short notice, which are frequently (and wrongly in Nato's view) described by the Russian military as being much smaller than they are to avoid pre-notification or the presence of outside inspectors.

Nato, in a word, wants Russia's behaviour to become more transparent and predictable.

At a time of growing tensions such predictability is a fundamental requirement if incidents or misunderstandings are not to escalate into potential crises.

- Published8 July 2016

- Published8 July 2016

- Published13 April 2016

- Published8 July 2016