Attack on Nice: How Nice sought to tackle jihad

- Published

The attack that killed 84 people in the French city of Nice has led to political recriminations and, yet again, probing questions about how to stop people turning to jihad.

Nice may have been caught off-guard when Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel's lorry ploughed into a crowd on Bastille Day. But city officials cannot be accused of having been oblivious to the militant danger.

Even before the Paris attacks of January 2015 served as a national wake-up call, they had mobilised to counter what many saw as a looming threat.

As far back as the mid-2000s, a Nice-based group of psychoanalysts and academics called Entr'Autres (Among Others) noticed a trend towards cultural separation and rejection of French values in immigrant areas.

Catherine Chavepeyre-Luccioni, a city councillor and teacher in a deprived area of Nice for 35 years, says she noticed long ago that such attitudes had become particularly strong among the young.

"In the old days," she says, "the mothers of my pupils were modern women. They never wore veils. Now the children do. The mothers wear veils as well, and tell me it's because their sons demand it."

Victimhood

By 2012, says Brigitte Erbibou of Entr'Autres, a sense of identity based on grievance had become common. "People were talking about conspiracies, the 'American-Zionist axis', she says. "They were openly taking anti-Semitic, anti-Western positions."

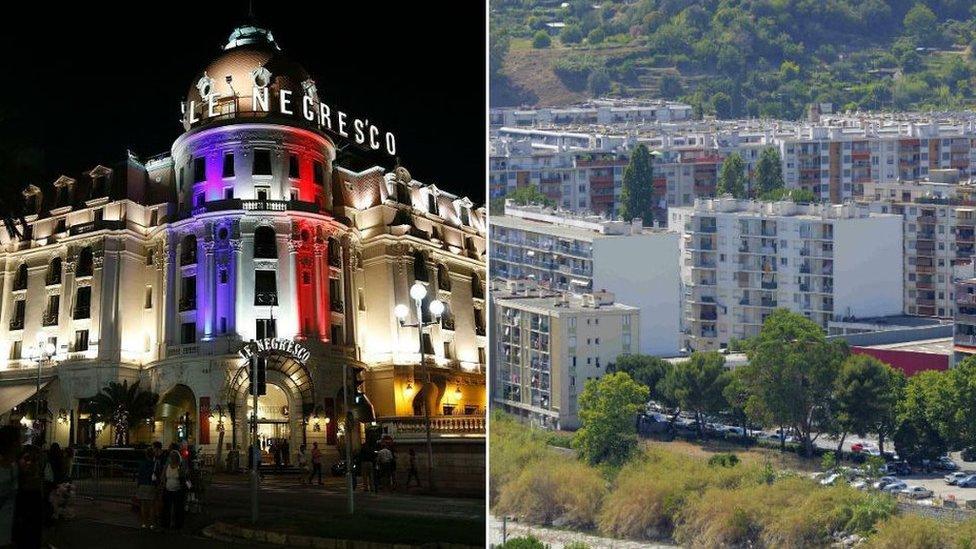

Most tourists know Nice as as a plush destination, but the city also contains deprived immigrant areas

Over the next two years, it became clear that the region had become a leading provider of jihadists - to date, 10% of French people who have gone to fight in Syria were from there.

Officials in Nice and the wider Alpes-Maritimes area took notice, and after the Paris attacks that killed 17 people in January 2015, they began watching the local situation closely.

A "radicalisation unit" for the region has been set up, bringing together teachers, social workers and security experts. They meet every week to report on and investigate any sign of trouble.

The mayor of Nice set up a 24/7 help line for families worried about fundamentalism. A dedicated team of counsellors was on hand offering psychological and legal help well before the Nice attack.

Earlier this year, when city officials were told that some football clubs had organised collective prayers, the mayor threatened to cut funding for those that did not respect a "secularism charter". The city also organises seminars for educators and grassroots workers.

Big brother

One of the most forceful speakers against radicalism in the region is Abdelghani Merah.

He is the brother of Mohammed Merah, a petty criminal from Toulouse who killed seven people during attacks on soldiers and Jewish schoolchildren in March 2012, before being shot dead by police.

Abdelghani Merah was once a petty criminal and has been to prison, but there the similarity with his brother ends

Mohammed Merah was the first home-grown jihadist to strike on French soil, and is still revered in radical circles around the country.

His elder brother Abdelghani, 39, says his aim is to redeem the family name by working with Entr'Autres to warn youngsters about the dangers of radical ideology.

"I want to smash the image of Mohammed Merah, who many youths consider as a superhero and a defender of Islam," he says.

"I am particularly useful when I talk to schoolchildren who are in danger of becoming radicalised and to mothers whose kids are being indoctrinated or have gone to Syria."

Abdelghani's main message is that France, far from being a land of miscreants bent on crushing Muslims, "is beautiful and has beautiful values".

Brother of Nice victim: "You killed my sister, you're not a Muslim"

Religious 'virginity'

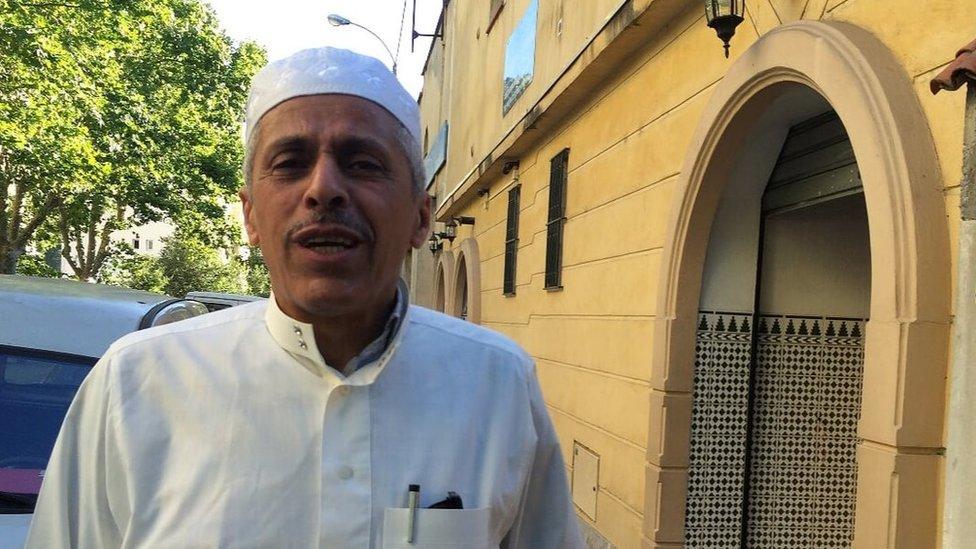

Religious leaders too play a critical role in the programme. One of them is Boubekeur Bekri, a no-nonsense imam in a housing estate sprawled along a motorway in north-east Nice, and vice-president of the regional Muslim council.

Around the time of the Merah affair in 2012, he noticed signs of radicalisation gaining ground in his impoverished neighbourhood. He has been doing his best to break the jihadist spell, but admits that his record is mixed.

Mr Bekri says he once lectured two brothers whom a mother had referred to him. "I told them that radicalisation was anti-Islamic, but unfortunately it did not work," he says. Two months later the pair were found with tickets for Syria, and promptly arrested.

Boubekeur Bekri is a leading Muslim cleric and long-time opponent of radicalism

But on another occasion, the imam says, a would-be jihadist was reconciled with his family after he had a word or two with him.

The challenge in trying to wean troubled youths off radicalism, Mr Bekri adds, is that it confers "religious virginity" on young offenders. They are easily convinced that they are doing God's work when they steal from infidels.

This redemption is all the more tempting when it provides an aura girls find attractive, Mr Bekri says. "You become Prince Charming."

While radicalisation often feeds on male dreams of military glory, for girls it typically involves fantasies of romance and humanitarian work.

Imene Ouissi, a 22-year-old student from an estate in Vallauris, recalls that two years ago a young man from eastern France approached her on Facebook.

Noting disapprovingly that she was not wearing a veil, he proposed to set her on the path of virtue by marrying her and taking her to Syria, where she would do good works.

Imene Ouissi says many young Muslim girls are lured into radicalism through the promise of marriage

Her life was not here among miscreants but in the land of the faithful, he insisted. She must do everything to get to the hereafter.

"Finding true love and is a feminine yearning," Ms Ouissi says. "Those youths have found ways to draw them into their circles through marriage. If I had been weak and had not been trying to understand true religion, I might have fallen for it."

Social networks and new media make people more receptive to the jihadist message, but actual recruitment still mostly thrives on old-fashioned personal contacts.

Nice was the home of France's most talented scout for al-Qaeda - Omar Omsen, a Senegalese-born militant who took 40 local youths to Syria, before fleeing there for good three years ago.

And according to one academic study, the areas of Alpes-Maritimes that have seen the highest numbers of departures for jihad are those that saw a large influx of former Algerian militants who moved to France after the civil war of the 1990s.

'Brainwashed'

It would be wrong to conclude that alienated youths from immigrant suburbs are the only people at risk of radicalisation.

"There is no typical profile," says Ms Erbibou. "They come from all backgrounds."

The mother of a middle-class girl living in an upmarket part of Nice described how her daughter - "Carole"- suddenly changed at the age of 13.

"She was a quiet, dutiful girl and an excellent pupil until she started mixing with troubled children from her school."

Tim Muffet examines the problem of extremism in Nice

Carole told her parents they would go to hell if they ate pork. To press her point, she showed them propaganda videos depicting how paradise and hell look like.

"It was like having your child taken away and brainwashed," the mother says. "It sent shivers down our spines. We never thought this would happen to us."

With the help of psychologists from Entr'Autres, Carole, now 16, pulled back from the brink of radicalisation. She has now embraced the tolerant, mainstream version of Islam.

But her mother says her daughter is not completely out of danger: "We are taking nothing for granted. We are vigilant."

The Nice area programme - combining action on the social, psychological, religious and security aspects of the problem - has attracted attention elsewhere in France, and beyond.

But its efficacy is difficult to assess. We will never know about attacks it may have prevented over the years.

And this long-term effort may be powerless against the sort of "rapid radicalisation" Lahouaiej-Bouhlel is said to have gone through.

Kamel, a youth worker in the area, believes that there are bound to be more such acts by freelance attackers. But he is even more worried about the repercussions of this and any subsequent attacks.

"In terms of pure statistics, he says, perpetrators represent a tiny fraction of the local Muslim Arab population," Kamel says. "But many Westerners will see their attacks as a huge setback for the possibility of harmony between Muslims and non-Muslims."