France responds to attacks with calls for peace and understanding

- Published

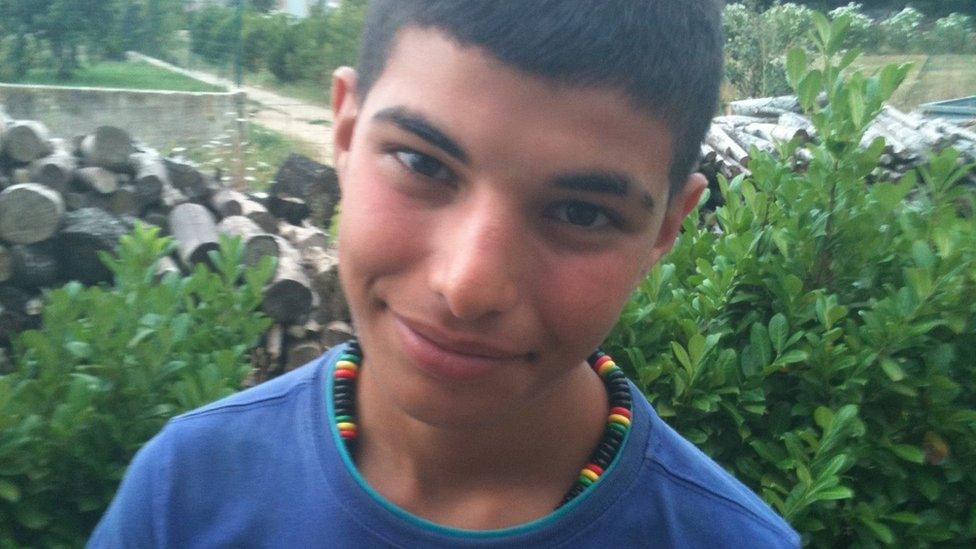

Father Jacques was among "three victims" in the church, the Archbishop of Rouen says

The murder of Father Jacques Hamel has triggered a bout of reflection among the French on a subject they normally avoid: their relationship with Catholicism and Christian ethics.

Like most European countries, France is in a post-religious phase of its history. Few attend church, and politicians who speak of "Judaeo-Christian" values are often dismissed as right-wing throwbacks.

And yet what the reaction to the jihadi murder campaign of the last 18 months shows is that people are far more influenced by their cultural and religious inheritance than they care to realise.

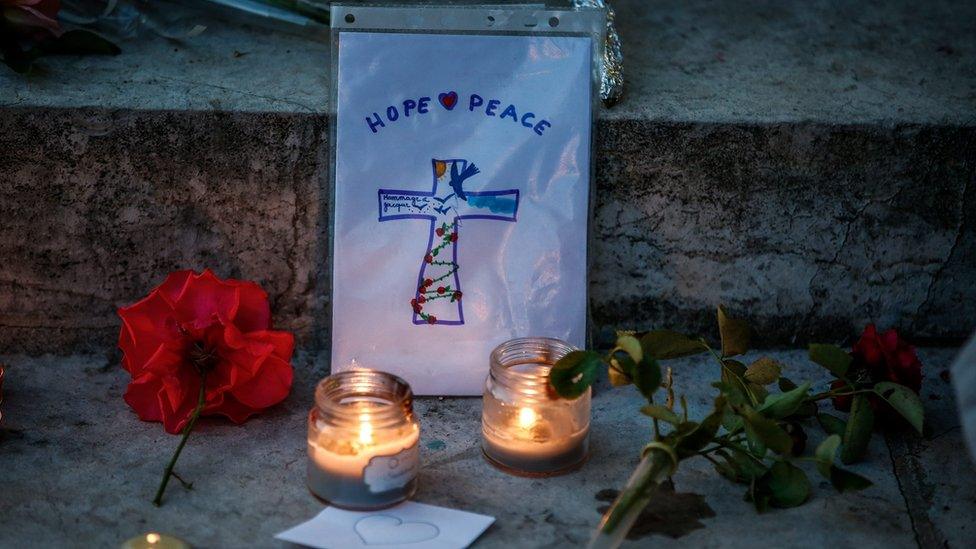

Since the killings began, there have been no crowds on the streets of Nice or Paris chanting "Death to Islamic State". Instead of flaming torches carried in angry procession, there are candles of remembrance.

European terror attacks

No-one in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray turned their attention to the nearby mosque. In the last 18 months, there has been no significant increase in crimes that target Muslims.

Instead there was the Archbishop of Rouen, Dominique Lebrun, on Tuesday saying that in the church of St Etienne there were "three victims" - Father Jacques and the two killers.

"Forgive them - they know not what they do," were the words he later quoted from the gospel.

Pain - but not hatred - has been the main reaction to jihadist murders

No-one in the country was shocked by the church's reaction to the murder of one of their own - no thirst for vengeance, no anathema against Islam; instead a plea for forbearance and understanding.

As the Archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Andre Vingt-Trois, put it: "Our belief in Christ should make us now not fighters and militants, but men of peace, reconciliation and love."

Broadly - stripping out some of the religious language - this is the same message that the politicians are giving out.

From the Socialist government, but also from the centre-right opposition, comes the constant argument: the aim of IS is to make us hate each other; they want our Muslim population to be isolated; they want acts of vengeance. Never let us cede to that temptation.

"Forgive them - they know not what they do," say church leaders of the killers

To be sure, there are also heated exchanges about levels of security and whether laws should toughened to target potential miscreants. But the essential ethic of tolerance and vivre-ensemble is taken as a given.

Even the far-right - though some might not like to admit it - falls within the mainstream now. When a party commands the vote of a quarter of the population, it can hardly be dismissed as unrepresentative.

And yes, it does call for tough measures like the expulsion of foreign offenders and stringent limits on immigration.

But there has been no visible far-right backlash. No arm-banded march-pasts in the banlieues. The Front National gives voice to an angry and often inarticulate part of the French population, but it has not gone down the way of violence.

Religious leaders from all faiths have met with President Hollande following the attack

Of course this might change - and the great fear today is that fringe elements on the nationalist far-right decide to take the law into their own hands. That way lies civil conflict and nightmare.

But so far one is bound to observe that the country has reacted to this horrific succession of provocations with good sense and an eye on the higher values.

Most French people will argue that these values - tolerance, respect between peoples, forgiveness, eschewal of violence - are part of the country's enlightened secular tradition.

But of course before that they were something else. They were Christian.

- Published26 July 2016

- Published26 July 2016

- Published28 July 2016

- Published26 July 2016