Are Russia's military advances a problem for Nato?

- Published

What does the performance of Russian forces in Ukraine say about the country's potential military capability against the Atlantic Alliance?

With tensions rising again between Russia and Ukraine, there are fears of a renewed upsurge in the fighting.

Russia-watchers in the West are monitoring events carefully, not just in terms of the day-to-day crisis, but because Russia's military is worth watching.

Moscow's military's performance in Ukraine has provided a foretaste of a new kind of warfare; eastern Ukraine has provided a laboratory for ground combat in the 21st Century.

Whatever Russia's ritual denials, its forces have played a significant role in the fighting in eastern Ukraine.

Mobilised rapidly from bases close to the Ukrainian frontier, they have undertaken a variety of combat roles.

For periods, fully formed Russian units have engaged directly in the fighting alongside pro-Russian militias.

At other times, it has largely been Russian "enabling" units that have provided crucial niche capabilities to their rebel allies - things such as air defence, electronic warfare, target acquisition and so on.

All of this has been watched by Nato forces, and by the Americans in particular, with rapt attention.

This is not the Russian army that invaded Georgia in 2008, which, despite its success, still showed many of the limitations of the old Soviet days.

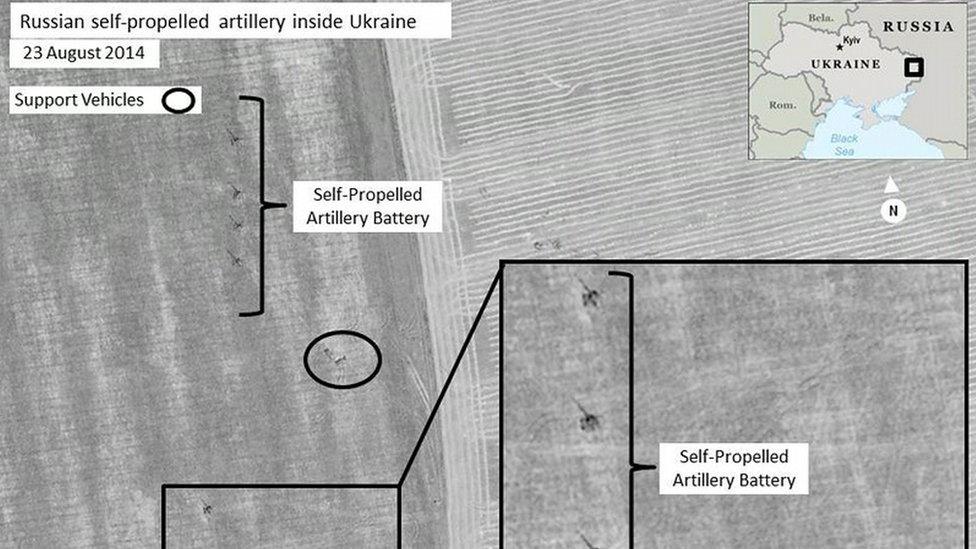

Nato said it had evidence that Russian forces were operating inside Ukraine in 2014

In Ukraine, the Russians have proved adept in many of the disciplines of modern high-intensity warfare.

In some areas, their skills and equipment are far more advanced than in comparable Nato armies. And many military analysts in the West are worried.

Russia's edge derives from the fact that, for well over a decade, the Americans and their allies have largely given up high-end mechanised warfare and have been fighting counter-insurgency campaigns in places such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

What high-intensity combat there was - the initial invasion of Iraq, for example - was brief and the Western forces were overwhelmingly dominant. They controlled the skies and could gather intelligence and communicate at will.

As the commander of US forces in Europe, Lt Gen Ben Hodges, noted ruefully in December of last year: "It's been a very long time since American soldiers have had to worry about [an] enemy up in the sky... having the ability to drop bombs."

Lt Gen Ben Hodges, commander of the US Army in Europe, has spoken of his concerns about electronic jamming

In terms of communications, he added: "We have not had to worry about being jammed or being intercepted, that sort of thing."

In the combat in eastern Ukraine, electronic jamming by specialised Russian units has been highly effective.

Indeed, Russia has won the battle in the electromagnetic spectrum hands down.

It has demonstrated a remarkable ability to locate Ukrainian units, to jam their signals, and then to bring down devastating fire upon them.

In some incidents, sizeable Ukrainian forces have been nearly wiped out in a matter of minutes.

The Russians have also shown a sophisticated ability to use drones, often in pairs; one to draw fire and the other to provide the targeting data for artillery or rocket forces who can instantly respond.

A recent British army study into Russia's performance raised question-marks about the survivability of some of its own newest, but lightly armoured, vehicles in this new environment.

Moscow has prioritised Russia's ability to wage cyber-warfare

But the improvements in the Russians' capabilities go well beyond the immediate battlefield.

Moscow has watched China's development of what is called an "anti-access and area denial strategy" - the development of ever longer range and accurate weaponry and targeting systems intended to push US naval carrier battle groups further and further away from its shores.

The Russians have taken a leaf out of the Chinese book, deploying similar systems of their own.

Russia's new air defences in Syria, for example, have radars that reach far out into the Mediterranean and well into the territory of Nato members such as Turkey.

The aim is to place at risk any forces approaching any area that Russia believes is of strategic importance.

But perhaps the most worrying element of Russia's new approach is what has been broadly termed "hybrid warfare" - a mix of semi-clandestine operations; propaganda and information warfare; computer hacking and so on.

This was seen in its seizure of Crimea with troops in unmarked uniforms (the so-called "little green men"); the closing down of independent news sources and so on.

What is fascinating from the Russian literature is the priority that Moscow gives to the whole cyber-domain, ranging from large-scale hacking to even the trolling of Western service personnel using their Facebook and Twitter accounts.

This has as much importance for the Russians as kinetic operations on the battlefield.

For the West, it poses a whole new set of problems, not least because it fundamentally blurs the boundaries between war and peace.