Burkini beach row puts French values to test

- Published

Security on French beaches has been tight this summer and the burkini row should be seen in that light

This is a controversy France could have done without.

Burkini or bikini, French commentators have asked, ironically, about this summer's choice of beachwear.

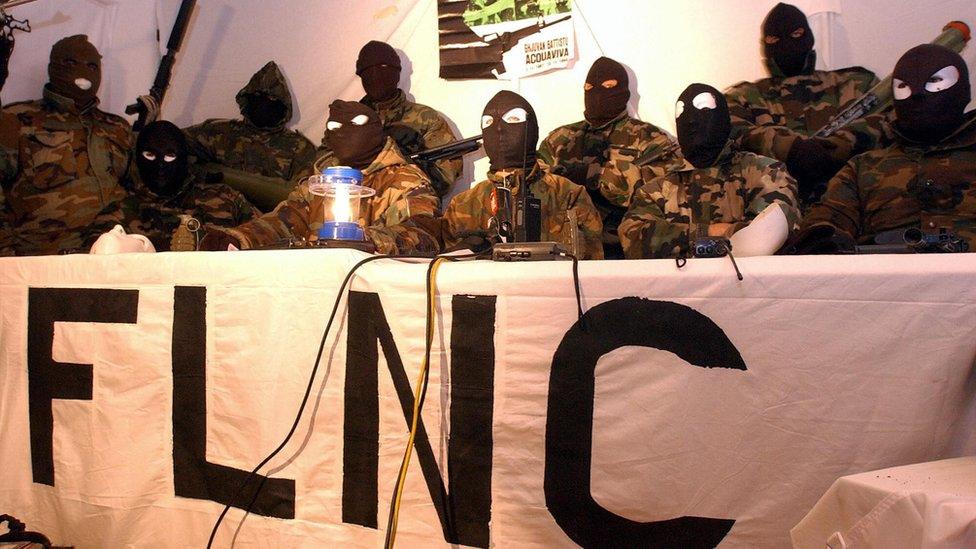

It is no coincidence that the ban on Islamic burkinis - full-body swimsuits - should arise from French Riviera beaches, a few kilometres from Nice, a city struck by a militant Islamist attack that killed 85 people on Bastille Day, just a month ago.

The town of Cannes was the first to pass the summer ban, which was confirmed by the courts on 13 August. And Cannes was soon followed by the towns of Villeneuve-Loubet, near Nice, and Sisco in Corsica.

Even the mayor of the northern seaside resort of Le Touquet is said to be about to pass a similar ban: no burkini will be tolerated on public beaches.

'Extremist symbol'

So far a small number of women have been fined (€38 in Cannes - £33; $43) for wearing a burkini on the beach at Cannes. And the mayor's decision has triggered a heated debate.

Cannes mayor David Lisnard has tried to explain his decision in these terms: "The burkini is like a uniform, a symbol of Islamist extremism. This is why I am banning it for the summer."

His view surprised the Cannes Muslim community, as David Lisnard is known locally for having allowed a large plot of land in his city to be used to build the Iqraa mosque, financed by a Saudi donor.

What do Muslim women think?

"I am a practising Muslim, and I believe there should be a choice," said Sabrina Akram, who grew up in Pakistan, and now lives in the US state of Massachusetts.

"I think it's outrageous that you would effectively be asked to uncover some flesh or leave," said Maryam Ouiles from Gloucester.

Read more here: Muslim women on the burkini bans

A French anti-Islamophobia association, CCIF, decided to challenge the Cannes mayor's decision in court but lost the case.

According to the administrative court which authorised the ban, it falls within the remit of the 2004 law restricting religious signs in public spaces.

France's anti-Islamophobia association says it will appeal against the court's decision to back the burkini ban

The court explained its decision: "In the context of a state of emergency and after recent Islamist attacks in France, the conspicuous display of religious signs, in this instance in the shape beachwear, is susceptible to create or increase tensions and risk affecting public order."

In other words, the court asserts that a burkini may not be seen simply as an innocent religious symbol, but as a militant and proselytising form of radical Islam.

Like many of his colleagues and a majority of the French people, Jean-Christophe Ploquin, columnist at Catholic daily La Croix, disagrees.

"In France, everybody is free to dress the way they like as long as they abide by the law. Everybody should therefore be free to wear a burkini," he argues. "This, however, doesn't mean we should be naive. The burkini offers a separatist vision of society and applies pressure on other women in the Muslim community."

Women in France

In fact, the burkini challenges two fundamental French values and traditions: women's emancipation and a desire to live together as one nation.

It was Brigitte Bardot who made the bikini popular in France

The country that gave the bikini to the world, following on a long tradition of influential women - from philosopher Madame du Chatelet, friend of Voltaire, to Coco Chanel, by way of Simone de Beauvoir, author of the ground-breaking female study The Second Sex - is shocked to see that some French women accept what it sees as the diktat of religion and of men on them.

Why the bikini became a fashion classic

The burkini also deeply challenges the notion of national unity, which is at the heart of the French narrative. The burkini is seen as a symbol of separatism and, for some, to allow it is to undermine the very idea of France.

The burkini controversy will probably slowly disappear as August draws to a close. It is nonetheless revealing of France's deeply troubled state of mind, one which is going to linger on for some years to come.

Agnes Poirier is UK editor for French weekly Marianne

- Published9 August 2016

- Published28 July 2016

- Published9 August 2016

- Published13 August 2016

- Published15 August 2016