Germany election: AfD tests Merkel in eastern region

- Published

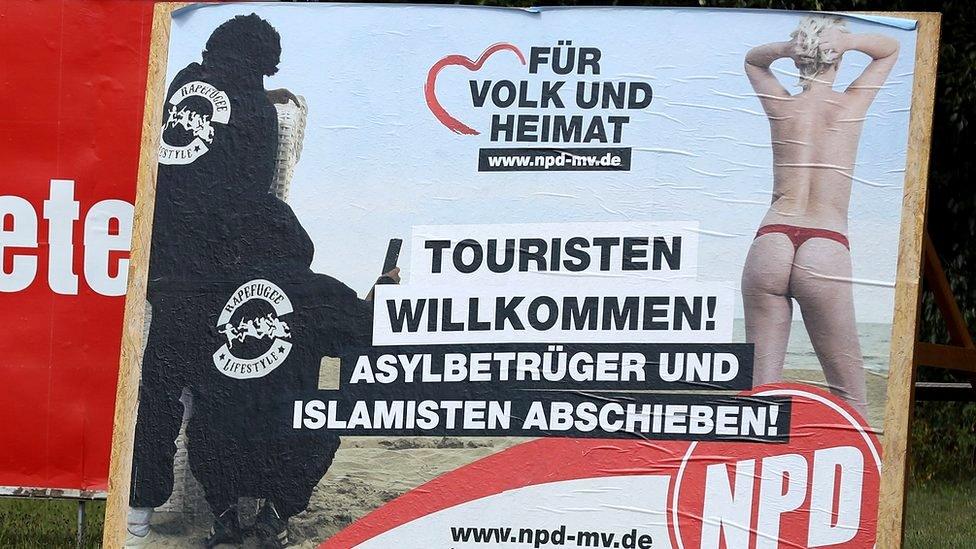

A far-right NPD poster: "Tourists welcome! Deport bogus asylum seekers and Islamists!"

In the tranquil, late summer warmth of Germany's north-eastern corner, election billboards scream alarming messages.

The far-right National Democratic Party (NPD) poster is certainly eye-catching - sinister, black-clad "rapefugees" juxtaposed with the rear view of a shapely, nearly naked white woman.

But nearby, in plain black and blue, there is a less visual but equally arresting message.

To those interested in mass immigration, criminality and pension security, it declares, vote AfD on Sunday "so that Germany is not destroyed".

The AfD poster says mass immigration and crime threaten to destroy Germany

AfD refers to Alternative for Germany, and is a populist, Eurosceptic party, founded just three years ago and already the country's fastest-growing political movement.

If the latest polls are anything to go by, the AfD is, for the first time, ahead of Chancellor Angela Merkel's conservative Christian Democrats (CDU) here in her home state, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania.

With the CDU also losing support in Berlin, which holds elections later this month, September could represent a significant milestone in Mrs Merkel's long political journey, as she ponders running for a remarkable fourth term as chancellor next year.

Chancellor Merkel (right) poses for a selfie on the campaign trail in Boldekow

In this largely rural state, commonly known as "MeckPomm", strident messages about immigration might seem a little hollow.

The state has taken in around 26,000 migrants since the current wave began in 2015. It is a small proportion of the estimated one million who arrived last year. Under a federal allocation system, Mecklenburg is expected to take in just 2.03% of all refugees.

But this region of the former East Germany is also poor and thinly populated.

Anti-immigrant rhetoric resonates. It is key to the AfD's success, a theme relentlessly highlighted in campaign literature and meetings with voters.

At an AfD campaign stop in Grosse Klein, a poor suburb of Rostock with a higher than average concentration of immigrants, the subject of foreigners, particularly Muslims, dominated.

"They don't fit here at all," party supporter Hannelore Schroter told me.

"When I see these women in public, completely covered, I think they shouldn't be here in Germany."

AfD candidate Leif-Erik Holm is the frontrunner in Sunday's election

At its party congress, earlier this year, the AfD declared that "Islam is not a part of Germany", and called for bans on burkas (full-body veils), minarets and the call to prayer.

"It's very difficult to integrate Muslims. People from a strange culture," party spokesman Roger Schmidt told me.

For some, the very name Rostock is synonymous with hostility to outsiders.

In 1992, the suburb of Lichtenhagen saw Germany's worst post-war anti-immigrant riots. Petrol bombs were hurled at apartment blocks housing asylum seekers, while thousands of local residents stood by and cheered.

Twenty-four years later, in Rostock's elegant city centre, the chilling sounds from that episode played from loudspeakers, as local activists commemorated one of the city's darkest hours. This, they warned, must not be allowed to happen again.

In recent weeks, popular protests in Grosse Klein forced the city to remove 15 migrant boys from a youth centre and cancel plans to build a new refugee shelter.

There is no suggestion the AfD was involved in the protests, but Martin Koschkar, a political scientist at Rostock University, says the party is making effective use of the current climate.

"The AfD benefits from this polarised debate," he told me.

Two terror attacks in July involving refugees have heightened security concerns across Germany. But Mr Koschkar says an underlying dissatisfaction with politicians is also helping to fuel the party's rise.

"They're mixing the migration topic with general criticism of the older parties."

Sunday's election in MeckPomm coincides with the first anniversary of the day, a year ago, when Angela Merkel decided to bring thousands of migrants to Germany on trains.

Coupled with her "we can do it" announcement, a few days earlier, it marked a turning point in Mrs Merkel's political fortunes. The rise of the AfD is just one of many consequences.

- Published13 August 2016

- Published6 July 2016

- Published10 March 2016

- Published1 March 2016

- Published14 August 2015