Russia's election and the need for legitimacy

- Published

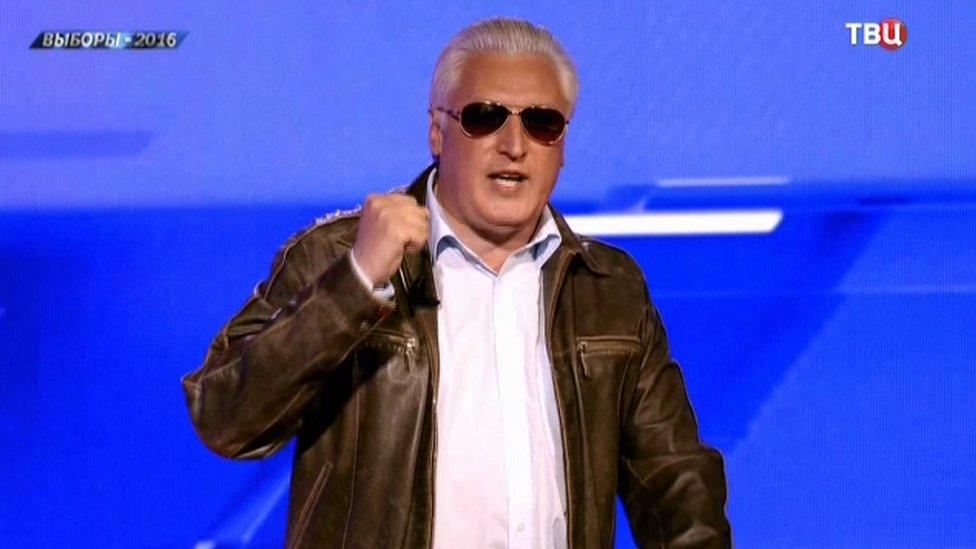

This Sunday's parliamentary election is the eighth which I have witnessed or reported on in Russia since 1989. And, so far, it has been the least interesting.

In Moscow there have been fewer election posters and banners on view than in previous years. Last week one Russian newspaper joked that the Duma election had been classified "Top Secret", since voters did not know the names of the candidates.

And yet, in theory, this election should have been more exciting than previous polls. A change to the law has permitted more parties to participate than in 2011 and even a handful of Kremlin critics have been allowed to run.

What's more, this time half of the 450 Russian MPs will be elected - not by party lists - but in single-mandate districts: the return to a system in which Russians can vote for a candidate of their choice in their own constituency.

However, the timing of this vote has kept public interest low. The Duma election had been scheduled for December. Instead the authorities brought it forward by three months, closer to the summer.

As a result, Russians have been more concerned with holidays, harvesting fruits and vegetables on their allotments and preparing for the new school year than with electing a new Duma.

President Putin and Prime Minister Medvedev visit fishermen during the Duma election campaign

But why the date change? How might the Kremlin benefit from a September, rather than a December, vote?

Kremlin critics claim the aim was to ensure that urban populations - traditionally, more critical of the government - had less time in which to mobilise for the election. A lower turnout is widely believed to benefit the ruling party.

President Putin will want the new Duma to be just as pro-Kremlin as previous incarnations. Even if the party of power - United Russia - fails to achieve an outright majority, the three other main "systemic opposition" parties (the Communists, Just Russia and the Liberal Democratic Party) should secure enough support to ensure the Duma remains, to a large extent, a Kremlin rubber stamp.

But this time, the Kremlin needs a parliament, which is more than just a rubber stamp. It needs a Duma which is seen by the people to be a legitimate institution.

The 2011 parliamentary vote was followed by anti-government street protests across Russia, sparked by what was widely perceived to have been large-scale electoral fraud: a rigged election in favour of United Russia. The protests were the biggest challenge Vladimir Putin had faced, although they waned after a Kremlin crackdown and differences among the opposition.

To head off protests this time, the Kremlin will be keen to ensure this election is not tainted by accusations of vote-rigging. Hence, the changes to the election law, the inclusion of some opposition candidates, as well as the appointment of a respected human rights advocate, Ella Pamfilova, to head the Central Election Commission.

Head of Russia's Central Election Commission, Ella Pamfilova

That does not mean the current electoral process is beyond criticism - as I have suggested, the decision to change the date of the election appears an attempt to influence the result.

Russia's economic problems make the need for legitimacy even more pressing. Eight years ago, the country's national reserve fund stood at $140bn (£105bn). Last week, Russia's deputy finance minister predicted the reserve would be exhausted in 2017.

That means more difficulties in paying social benefits, pensions and the salaries of state employees. The government may have no choice soon but to embark on unpopular economic reforms.

This has implications for the vertical system of power Vladimir Putin has constructed in Russia, with the president at the top and all other institutions - including parliament - below and subservient to him.

That system worked while the economy was working.

But the money is running out, social protest is on the rise. The danger for the Kremlin is that if Russians question the legitimacy of other institutions in their country - including their parliament - they pin all of their too many hopes on the one man at the top.

- Published10 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016

- Published5 September 2016

- Published25 August 2016

- Published25 March 2024