How Spanish activists landed ex-IMF head Rodrigo Rato in court

- Published

"End of an era": Rodrigo Rato, once hailed as an economic genius, is taken from his office by police for interrogation in April 2015

An initiative launched by a handful of political activists in 2012 is on the verge of striking the biggest blow yet in a fight over allegations of political corruption in Spain.

On Monday, dozens of former members of the board at Spanish bank Bankia go on trial in Madrid on charges of misappropriation and fraud.

Among them, the activists' prize catch: former minister and IMF chief Rodrigo Rato, who denies any wrongdoing.

How did we get here?

It all began at a meeting in Barcelona over four years ago, held to mark the first anniversary of the 15 May 2011 "indignado" ("indignant") protests against corruption and cronyism.

"Why don't we have Rato sent to prison in five years' time?" asked one attendee.

"So we drew up a rational plan with a reasonable production timeframe towards that goal," says Sergio Salgado drily. He is a leading member of the campaign group 15MpaRato, which is directly responsible for Mr Rato going on trial.

Protesters demand justice for "all the guilty thieves" in 2014

"We have nothing personal against him," explains Mr Salgado.

"He is the symbol of the revolving doors culture. He has been a minister, then managing director at the IMF and a banker. And he was a very well-known figure," says Simona Levi, another leading figure in 15MpaRato.

Who is Rodrigo Rato?

Now 67, Mr Rato was economy minister in the conservative Popular Party (PP) governments of Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar from 1996 to 2004. Mr Rato was often credited with being the "mastermind" of Spain's economic boom, before it turned to bust when a real-estate bubble burst in 2008.

When the PP lost power in 2004, Mr Rato became IMF chief, a post he suddenly left in 2007 for "personal reasons". In 2010 he was named chairman of Bankia, a bank formed by the fusion of Caja Madrid with other public savings banks, all struggling to deal with the blowback from years of easy lending to construction projects.

On his watch, Bankia became the bank that symbolised Spain's financial crisis.

As Spain's fourth biggest bank, it listed on the stock market in July 2011

Bankia said initially it had made an operating profit in 2011 of €305m (£265m; $340m)

But then a May 2012 audit demonstrated that it had actually lost €3bn

Mr Rato was forced to resign as Bankia chairman and the bank was nationalised at a cost of €22bn in public money

The shares bought by over 200,000 small investors became worthless overnight

What did the activists do?

The small team at 15MpaRato started compiling evidence of what they saw as fraudulent information given to people with accounts at Bankia who had been given the chance to buy "preferential" shares before the flotation.

They encouraged small investor "victims" to come forward, sue Bankia, and help them build a credible narrative with which to persuade public prosecutors to take action.

Bankia eventually agreed to give back €1.5bn to the approximately 200,000 who had bought preferential shares when Spain's courts accepted a Bank of Spain report that established there had been deception.

Mr Rato's role in this alleged fraud is still being investigated with no date set for that trial yet.

Rodrigo Rato and the case of the 'black credit cards'

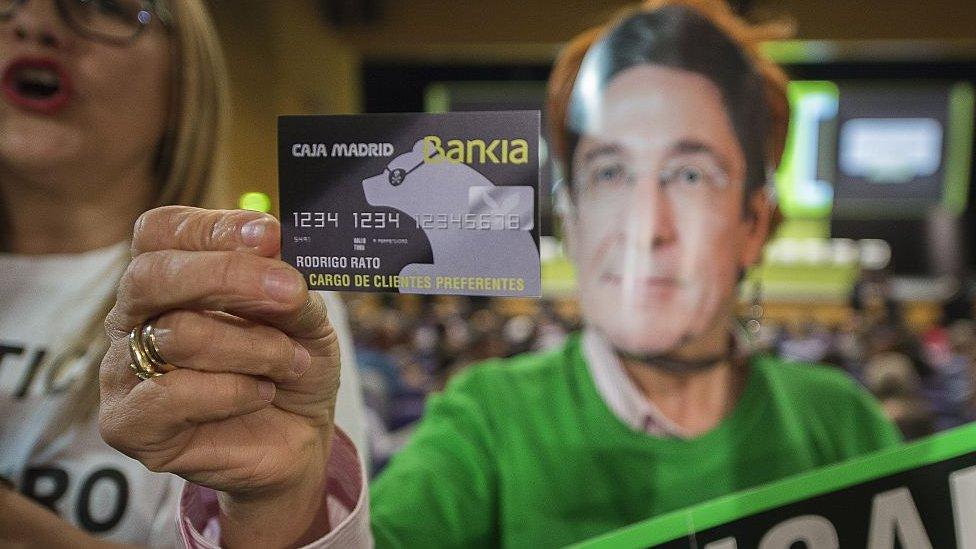

What no-one expected was the case of the "black credit cards" - and that is why the former Spanish economy minister goes on trial on Monday.

The evidence arrived in 2013, when Simona Levi opened a whistle-blowing email.

In the email was a complete list of people accused of using secret credit cards issued to board members and advisers at Caja Madrid and later Bankia, as well as claims about what they had spent their money on.

The 'black credit card' scandal "offended people's innate sense of justice", says Mr Salgado

"At first you read these huge amounts of information that come through that account and you don't take it too seriously. But then we began to think 'wow, this is a real treasure'," Ms Levi recalls.

The list was a who's who of Spanish political life, including representatives of political parties from the left and right, unions, a secretary to Spain's royal family and the bank's top management, including Mr Rato. And the 15MpaRato activists shared it with Spanish media.

The total sum spent between 1999 and 2012 amounted to €15.5m - money supposedly meant to cover the costs of attending board meetings, but often allegedly used for personal items or simply taken out of cash machines.

"The amount was not the thing. It offended people's innate sense of justice. We all go to cash machines; you might have some money in there, sometimes not enough. But these people always had what they wanted," says Mr Salgado.

What are Mr Rato's prospects?

The 'black credit card' case has enraged former shareholders in Bankia

Mr Rato faces a possible jail sentence of up to 10 years if found guilty of running and expanding the secret credit card system, and may be put on trial in at least three other cases.

Prison would complete the downfall of a man once considered a probable prime minister of Spain but who in 2014 felt forced to give up his PP membership card.

In 2015 it emerged that he was being investigated for tax fraud after taking advantage of a fiscal amnesty three years earlier, repatriating money he had been keeping abroad. This investigation caused him to be briefly arrested in April 2015.

He denies any wrongdoing.

Rodrigo Rato's fall from grace

When he was arrested in 2015, El Mundo newspaper wrote of "a point of no return, in which we leave behind an era"

2004: Mr Rato leaves Spain's economy ministry to head IMF

2007: He returns to Spain after three years in Washington, citing unexplained personal reasons. An internal IMF report in 2011 criticised the organisation under Rato's leadership, saying it "failed to anticipate the crisis, its speed and magnitude"

2010-12: During his 18-month stint at Bankia, Spain sees the unravelling of the biggest banking disaster in its history, prompting an EU bailout of Spain's financial sector

July 2012: Mr Rato is called to court to explain Bankia management, following complaints from 15MpaRato and political party UPyD

2013: His name crops up in the "black credit card" affair

2014: Mr Rato resigns from Popular Party

2015: Arrested for seven hours during police search of home and office .

2016: Panama Papers leak reveals Mr Rato as a client of Mossack Fonseca, which helped him to wind up two offshore companies worth €3.6m