Migrants' grim odyssey ends in Italian city of Udine

- Published

One of the young migrants heading to Italy from Austria, hoping to get asylum

Two men stood on the platform at Villach station in south-east Austria, waiting for the local train to Udine in Italy - not far across the border.

They looked nervous and out of place, among the cyclists and tourists heading south.

One looked Arab, the other Pakistani or Afghan. From time to time, they glanced around furtively.

When the train arrived, they boarded separately and sat in different compartments.

Half an hour later, the train crossed into Italy, and stopped at Tarvisio station in the Alps.

Italian border police got on the train - and pulled the two men off, probably because they did not have proper documents.

It is likely that they claimed asylum in Italy, and were brought to the city of Udine, about 100km (62 miles) further south, to be processed.

While most migrants coming to Europe try to head north to countries like Germany or Sweden, in this region of northern Italy the flow is in the other direction.

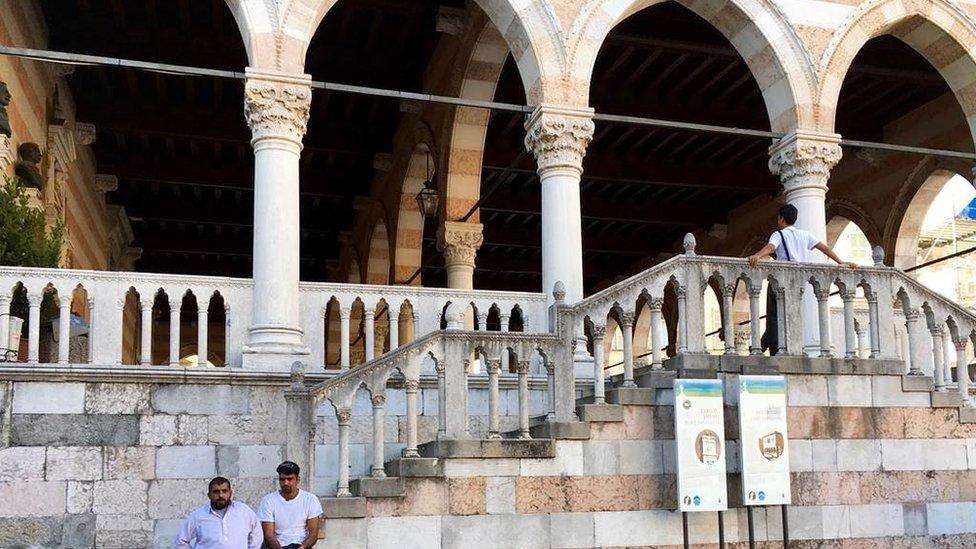

The overwhelming majority of migrants in Udine are young male Afghans and Pakistanis

Migrants have been criticised for loitering in Udine city centre and over-using the free wi-fi

"From the beginning of January 2016, there have been about 5,000 migrants coming via Austria to Italy, to Udine," said Udine provincial prefect Vittorio Zappalorto.

"Mostly they come here because their application for asylum is not accepted in other countries."

He says about 90% of them are from Pakistan or Afghanistan. The overwhelming majority are young men.

Deported

Udine, home to 100,000 people, has struggled to cope with the stream of new arrivals. Two years ago, many of them had to sleep rough.

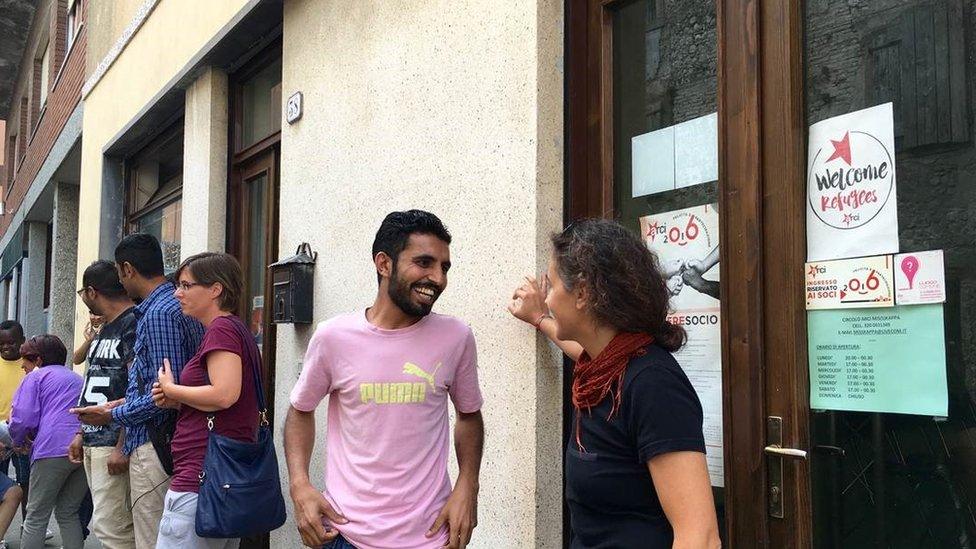

Volunteer organisations offer migrants in Udine free Italian lessons

Migrants face a long, grim wait living in an old army barracks converted into a hostel

The city has now set up shelters in flats and at two old army barracks, where the asylum seekers are fed and housed.

At one of them, the Caserma Friuli, I met Salaam, a 25-year-old Afghan. He said that in 2009 he lived in Britain, but was sent back to Afghanistan. In May, he arrived in Udine, via the western Balkan route.

When I asked him why he had not applied for asylum in Austria or elsewhere he said he had heard that in Italy "they give you documents".

Salaam, 25, lived in Britain until 2009, then was deported to Afghanistan - and arrived in Udine in May via the Balkans

The mayor of Udine, Furio Honsell, said many migrants seem to be coming here as a last resort.

"People come here because they think that in Italy there is an option," he said.

"You can either get asylum or what it is called temporary protection or humanitarian protection, and it allows them probably to go back to other countries where they can get a job.

"The situation is chaotic. These people are orbiting Europe trying to build a life for themselves."

Mayor of Udine Furio Honsell says many migrants seem to come to the city as a last resort

Europe's migrant crisis:

Mr Honsell says that according to Italian law, just about anybody who is on Italian land can apply for asylum and can appeal twice if their case is turned down.

"This sets up a process where people stay here," he said. "There is basically no deportation in Italy."

Some migrants believe they have a better chance of getting asylum in Italy than elsewhere

Mr Honsell says there is not much work for the migrants in Udine, which is in the grip of a recession.

Many spend their days hanging out in the city's Venetian centre, using the town's free wi-fi - something that upsets some of the locals.

"They do nothing," one man told me. "They have no respect for us, their hosts. It is not true that they all come from war-torn countries. There are people who shouldn't be here."

A volunteer association, Ospiti in Arrivo, is trying to bridge the gap by offering free Italian lessons.

One of their students, Hassan from Pakistan, told me that although "the standard of living isn't very good", Italy is the only EU country that "can give you a future, because after two or three years they will give you papers".

Hassan from Pakistan says Italy is the only EU country that gives migrants a future and the correct papers

But surviving the long waiting process is harsh - and getting papers is not guaranteed. Many may eventually join the ranks of Italy's undocumented migrants, the "clandestini".

Volunteers from Ospiti in Arrivo regularly check Udine's train station and its parks to help migrants who are trying to enter the asylum system or who have fallen out of it.

In one park, we met Abdullah from Afghanistan. He told us he had been sleeping there for a month, because he had lost his ID and had been refused re-entry to a local shelter because he had gone to Milan for a few months.

The volunteers gave him tea, biscuits and a blanket and advised him to visit the charity, Caritas, the next day.

"It is not easy to live here illegally," Lisa, one of the volunteers told me. "I don't know if people really want this, sleeping in the park or not having a job.

"We think people are coming here because of war and violence, not because we are kind. We are doing something very human. We tell them where to go, where to eat and try to give them advice. We don't want them to be illegal."