Italy earthquake: Race to help homeless as nights turn cold

- Published

Roberta and Samuele now live in a tent in the garden of their house in Piedilama

Survivors of Italy's deadly earthquake all have a different story to tell of the day their homes crumbled and their lives fell apart.

For Roberta, a mother-of-four, it was being asked Why Mummy, was there fog hanging over the village, as she gazed into a cloud of dust on the morning of 24 August.

For Samuele, her youngest, it was the work of a monster that lives in the back garden of his damaged house. Samuele turned four on Monday. He still covers his eyes not to see the creature, each time he goes across the lawn to their tent to sleep.

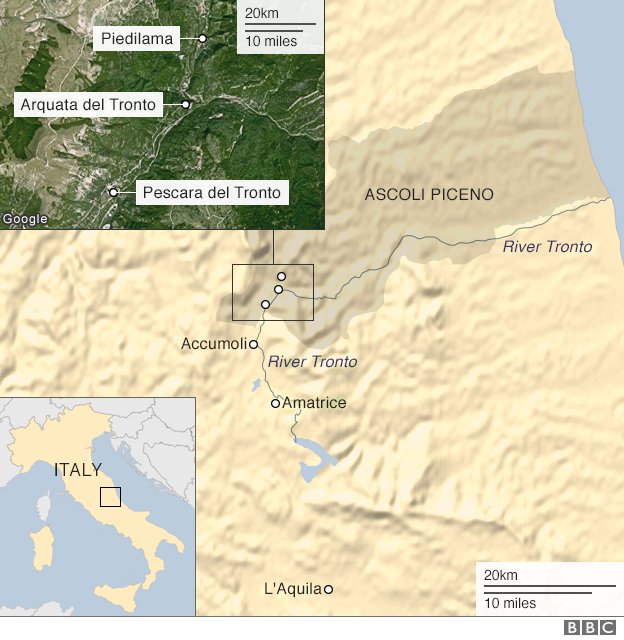

For Enzo, it was all about emerging unscathed. Road signs still lead to Pescara del Tronto but the village is gone, except for Enzo. He survived on a couch in his kitchen because the floor above held when the two floors above it came crashing down.

For Francesco, a rescue manager, it was getting home in the early hours after a night out, climbing into bed and immediately being shaken out of it. He and his team scrambled to search for survivors in the rubble of Enzo's village. Hunger, thirst and fatigue did not get in their way.

How bad was the quake?

The 6.0-magnitude earthquake claimed 298 lives. In human terms it was as bad as a 2009 quake that wrecked the city of L'Aquila and left 309 people dead.

Fewer people lost their homes this time. Currently, 2,233 are still being cared for in camps or other temporary structures while in 2009 there were 58,000 homeless.

The government has estimated the cost of repairing the damage at €4bn (£3.5bn; $4.5bn) compared with a projected cost of €21bn for L'Aquila.

Rubble fills the square in the shattered hilltop village of Arquata del Tronto

The village is now a no-go area

Flowers still dot the deserted village

Less easy to calculate is the psychological damage from the new disaster which:

struck in the same region

had a similar magnitude of 6 (L'Aquila was 6.3)

had a similar depth (8km or five miles, compared with 8.8km for L'Aquila)

happened at much the same time - 03:36 whereas L'Aquila was at 03:32

"It's as if we've been wounded," says Francesco Lusek, who has worked on five earthquake relief operations and taken part in humanitarian missions in the Middle East for Italy's civil defence agency.

"These are our mountains. We have friends and family here. We love to come here to hike. It hurts."

Rescue manager Francesco Lusek feels a personal connection to the villages damaged by the quake

The rescue team worked non-stop for hours to save people in Pescara del Tronto

Four regions suffered damage - Abruzzo, Marche, Lazio and Umbria - but the disaster will forever be associated with the picturesque Lazio village of Amatrice, a tourist destination with a population of 2,650 where 236 died.

Yet, with a permanent population of about 100, Pescara del Tronto suffered a greater loss in relative terms: 34 local people died along with 12 tourists in this Marche hamlet.

What is it like for the homeless?

On a football field below the shattered hilltop village of Arquata del Tronto, which like nearby Pescara is now a no-go area, blue tents house homeless people.

The biggest tent is a canteen where hot meals are served to residents and relief workers. Roberta Pompa and her family drive down to eat there from their own village, Piedilama, where there has been no gas since the quake.

The camp at Arquata del Tronto provides temporary homes for many of the displaced

A tent primary school has been set up and two containers hold makeshift stores selling essential items.

Emergency service vehicles criss-cross the valley's roads while soldiers guard the ruined villages against looters. Any visit to one of these "red zones" can only be made under escort because of the risk of an aftershock toppling damaged buildings.

The slogan of Marche's disaster response is "mai soli" (you'll never be alone).

What happens next?

Marche is determined to move all its displaced people into hotels by 1 October. Those who find shelter elsewhere will receive €600 a month per family.

After that, wooden houses will be erected for those who need them within 12 months.

Roberta and her husband Alessandro Paci have a dilemma. The roof of their house was damaged but did not fall in and they hope it can be repaired.

From the outside, damage to Roberta and Alessandro's home looks small but the roof is unsafe

Roberta and Alessandro's family are sleeping in tents for the moment

Meanwhile, the family sleep in the tent because a strong enough aftershock could bring the roof down. But the winter gets bitterly cold in the mountains.

The winter will also be tough for Enzo Rendina. The last person living in Pescara del Tronto refuses to leave because he fears the village will disappear if it is abandoned now.

Civil defence staff bring him food.

Enzo Rendina compares the sound of the earthquakes in 2009 and 2016

But the likelihood is that these ruined villages will be rebuilt because there are few alternative construction sites on the valley's slopes. It was a different story in L'Aquila, where the devastated old city has been left temporarily abandoned and new buildings erected in the suburbs.

One day soon, the people of Marche hope that the fear will pass and the Tronto Valley will again fill with holidaymakers.

Thirty-four residents and 12 tourists died at Pescara del Tronto

The rubble of Pescara del Tronto

Margherita Rinaldi and Antonio Filippini of the Marche Region media team helped compile this report.