Will Brexit take the sweetness out of the sherry trade?

- Published

The UK has long been the biggest market for exports of sherry

Before there was Brexit - before there was a European Common Market or a Treaty of Rome - there was the sherry trade.

Shakespeare sang the praises of the golden fortified wine from the sun-griddled vineyards of southern Spain.

The English in particular have been drinking it by the barrel since Sir Francis Drake began looting supplies from the Spanish harbours he attacked.

The sherry wineries or bodegas in and around the southern city of Jerez de la Frontera are a handy vantage point from which to survey the trade landscape of post-Brexit Europe - an EU minus the UK.

Tradition is everything in the sherry vineyards of southwestern Spain

On the one hand, times have been tough in recent years - sales of mass-market sherries have plummeted in the years since the 1980s, when every household in the UK kept a cheap bottle to hand, to pour into trifles on Sundays and relatives at Christmas.

On the other hand, the trade has historically showed extraordinary resilience at difficult historical moments, emerging successfully from World Wars One and Two, the Spanish Civil War and the Great Depression.

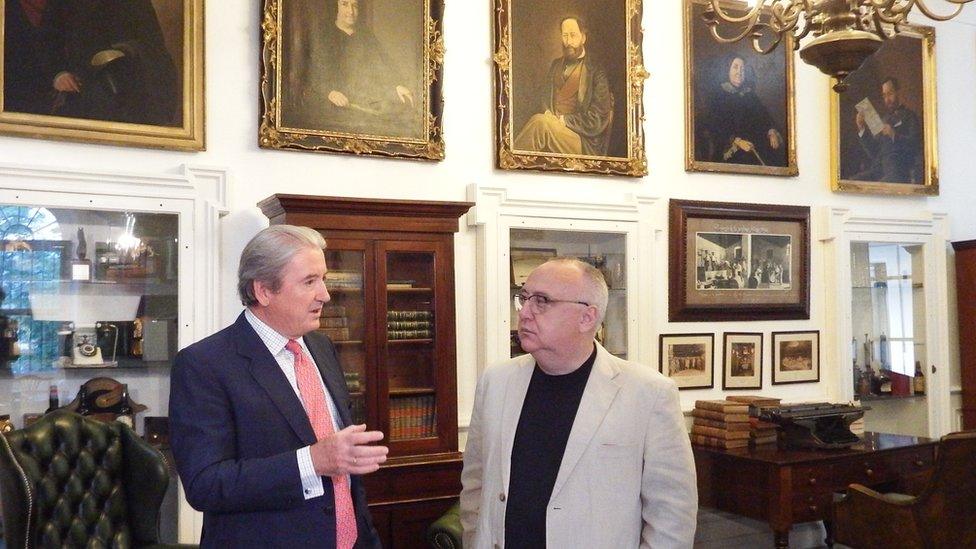

It was a point emphasised to me by Pedro Revuelta Gonzalez, in the elegant wood-panelled library of the Gonzalez-Byass bodega in Jerez.

Pedro Revuelta Gonzalez (left) believes Brexit will not hurt British and Spanish consumers too much

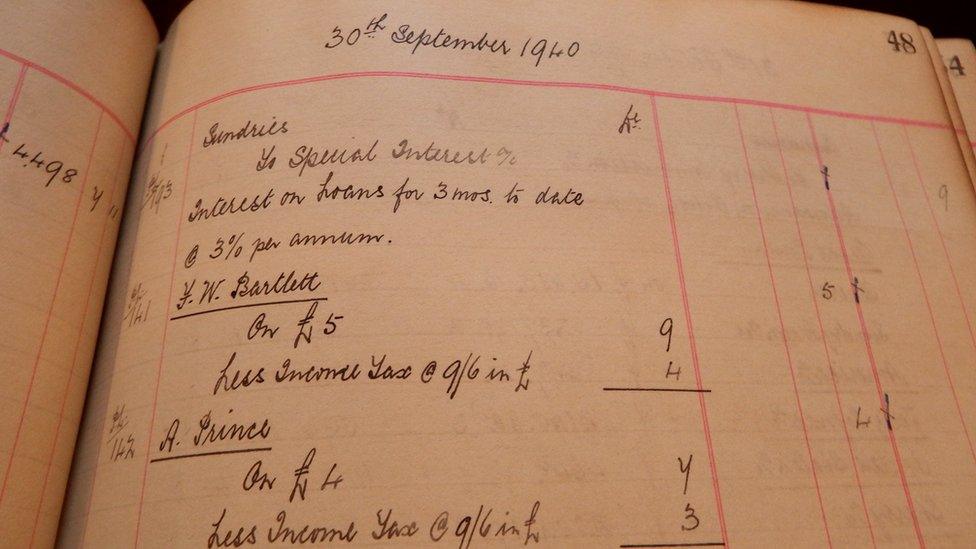

The company ledger from the 1940s, rescued from the Blitz in London

He produced from the archive a ledger neatly recording the company's business in Britain during the early 1940s - the years of the Blitz and the Battle of Britain. The neatly-bound ledger, with handwritten entries in faded fountain-pen ink, was recovered from the wreckage of the company's London office, which was damaged in a German air raid.

Mr Gonzalez favours a soft Brexit - one which protects not only the interests of the sherry trade, but also those of the British expatriates who live on the coast, a short drive to the south, and the huge numbers of Britons who come every year to the resorts of Benidorm and Torremolinos.

"We believe in free trade," he told me. "And we hope and we're sure that the regulators in the UK and Europe also believe in that. So they'll try to find a solution that will be good for Britain, for Europe and of course for consumers, so there won't be big barriers in commerce."

If Brexit were to become a bitter affair, which involved British departure from the EU customs union and the single market, and strong restrictions on freedom of movement into the UK, then in theory at least those tourists in future might require a visa for their Spanish holidays.

Perhaps because this region of Spain has such close links with the UK, that confidence that a benign Brexit deal can be arranged seems fairly widespread.

Five models for post-Brexit UK trade

What does 'hard' or 'soft' Brexit mean?

How does leaving the EU affect expats?

In a party of British tourists on a tour of the Gonzalez-Byass bodega I met Mick Irwin and Glenys Nicholls, who told me they voted for Brexit. And if there are Brexiteers experiencing "Buyer's Remorse", as some commentators have suggested, then Mick and Glenys are not amongst them.

"No, no, no way - that's it, we've made our decision," Glenys told me. "I hope they don't go back and do another vote, because it's not the best of three until the other side get their way. We're coming out, come what way, and we'll just have to stand by our conviction and survive one way or the other."

When I asked Mick if there was some sort of contradiction between voting Brexit and then heading off to an EU member state on holiday he couldn't have been clearer.

"Not at all. They still want to sell us their sherry and they want to sell us their sun and sangria and they'll be cutting off their noses to spite their faces if they try to put British tourists off."

Global sherry sales declined after the 1970s but picked up again in recent years

There was a general sense of surprise in Spain at the UK's vote to leave the EU.

Spain joined the EU only a decade or so after the death of the dictator Francisco Franco, and membership here is associated more with an anchoring of the democratic process and a modernising of the economy, than with unnecessary bureaucracy and untrammelled immigration.

Benalmadena, Costa del Sol: Some 309,000 British expats are resident in Spain

Eugenio Camacho, the presenter and editor of a news programme on Radio Jerez, put it like this:

"The concerns about Brexit are mostly in terms of the historic commercial relations over sherry between Jerez and Great Britain. More than fear, there's uncertainty. At the moment when the consumption of sherry has started to recover in an important market like the UK this really puts the brakes on that recovery."

The process of negotiating the terms on which the UK leaves the EU has not yet begun. And it is possible that when it does it will be long and tortuous.

Southern Spain, with its strong historic British trading links, provides a reminder that when the EU is trying to settle on a negotiating strategy there will be voices calling from within for a soft Brexit and a soft landing - for what may be a difficult and protracted process.

- Published29 September 2016

- Published12 June 2017

- Published4 July 2016

- Published27 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016