Whistle-blower who took on Spain's ruling elite

- Published

Ana Garrido's whistle-blowing led to clinical depression and her giving up her civil service career

Is ruining a comfortable, middle-class life a price worth paying, if it means bringing rich and powerful people to justice on alleged corruption charges?

Ana Garrido thinks it is. The 50-year-old former civil servant's personal investigation played a key role in exposing a massive corruption network linked to Spain's ruling Popular Party (PP).

But it is her life that has been ruined.

When 37 accused, including an ex-minister and the PP's former treasurer, go on trial in Madrid on Tuesday, it will mark a milestone in the fight against corruption in Spain.

But Ms Garrido no longer works at the council in Boadilla del Monte, a leafy Madrid suburb, where almost a decade ago she realised that something shady was going on. Instead, she has turned to making and selling handicraft jewellery to pay her rent.

She started working at the council in 1993. Then in 2007, as part of her role in the youth department, she says she received strange instructions to favour certain companies when contracts were to be awarded.

"Cut corruption": Protesters in Madrid vilify PM Rajoy and PP General Secretary Maria Dolores de Cospedal

She cross-checked data and found that under the PP mayor of Boadilla at the time, Arturo Gonzalez Panero, a network of firms was being favoured without due process.

"I was passionate about my job working with young people and children. I had a good salary, I was buying a nice home and travelled a lot. I was a very happy person."

When Ms Garrido began to realise the dimensions of a scandal that spread far wider than the confines of her home town, she felt scared, exposed and vulnerable, she says.

"There is nothing like a whistle-blowers' charter in Spain. Not only are we not protected, but we can be persecuted and harassed by those we accuse of abusing power."

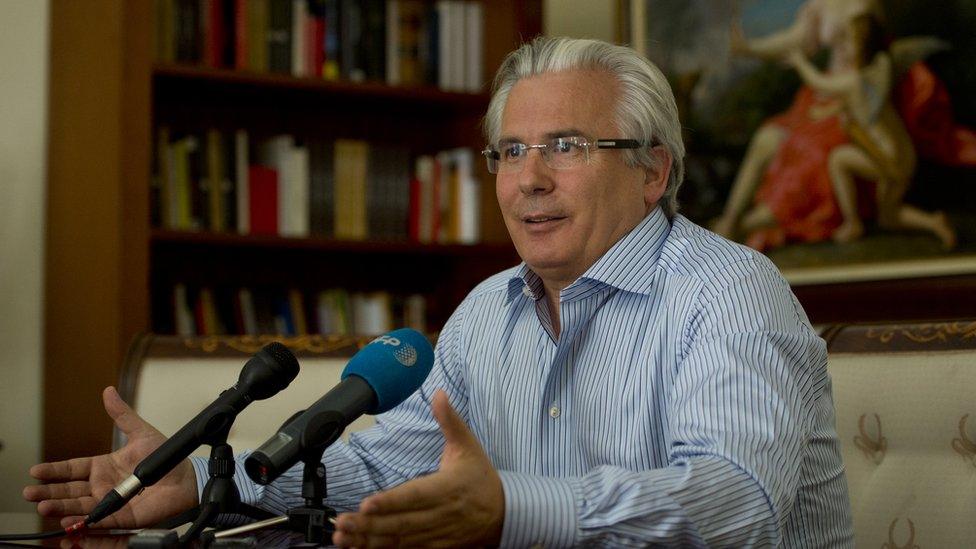

Judge Garzon has pursued various high-profile human rights and corruption cases

Ms Garrido's evidence ended up in the hands of investigating judge Baltasar Garzon. But her treatment at work led to clinical depression and, eventually, giving up her civil service career.

"My bosses held meetings without me, made me change office over and over and halted each project I was working on. Every day when I went in, I just didn't know what was in store for me."

Eventually, Ms Garrido won a lawsuit against the council for harassment, but she has not yet seen the €95,000 (£82,000; $106,558) awarded to her as compensation, because Boadilla town hall has appealed against the ruling. And the conservative PP has reported Ms Garrido for keeping public documents in her home.

How the PP scandal unfolded

2009 - Ana Garrido's evidence reaches Judge Baltasar Garzon (famous for ordering the arrest of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet), who is investigating an allegedly corrupt network of PP politicians and businessmen, headed by Francisco Correa. The case is named Gurtel (German for "correa", which means "belt")

From Madrid dormitory towns such as Boadilla del Monte evidence emerges of a system whereby companies under Mr Correa's influence allegedly organise party events free of charge for the PP and receive lucrative public contracts in return

2010 - Judge Garzon is hauled off the case and eventually suspended for 11 years for abusing his authority in ordering that telephone conversations between imprisoned suspects and their lawyers be taped, as he believes they are conspiring to destroy evidence

2013 - Handwritten ledgers, allegedly kept by former PP treasurer Luis Barcenas, come to light as the Gurtel investigation expands into a probe into the party's finances. Mr Barcenas is arrested and found to have tens of millions of euros in Swiss bank accounts

2016 - Case finally reaches trial stage, with 37 people in the dock, including Mr Barcenas, Mr Correa, and Spain's former health minister, Ana Mato. The trial covers the period 1999-2005, with investigations into later years and the PP's alleged slush fund still ongoing

Ms Garrido also claims to have been vilified by sections of the Spanish media.

"Even some of my friends have asked me if I have tampered with documents. This is what they do; the aim is to discredit the whistle-blower, and it has not happened only to me."

Ex-PP treasurer Luis Barcenas is accused of having run a slush fund for PP politicians

In Andalucia, the UGT labour union is trying to have former employee Roberto Macias jailed for four years, for stealing computer files that helped uncover alleged fraud in the use of government subsidies.

Ms Garrido says that all of the parties in Spain's parliament are receptive to her Platform for Honesty's proposals to establish certain legal safeguards for whistle-blowers - all except the PP.

So has it been worth it, or is Spanish politics just as corrupt as it was in 2007, when Ms Garrido's life changed for ever?

"There is still a great deal of corruption in Spain, but today perhaps people will think twice about taking things that they used to assume was their right. I would do it all over again, but I have only managed to get so far because I don't have children. It is not the same to suffer extortion and threats directly if it affects the life of your children."

- Published9 July 2013