UN secretary general: The hardest job in the world?

- Published

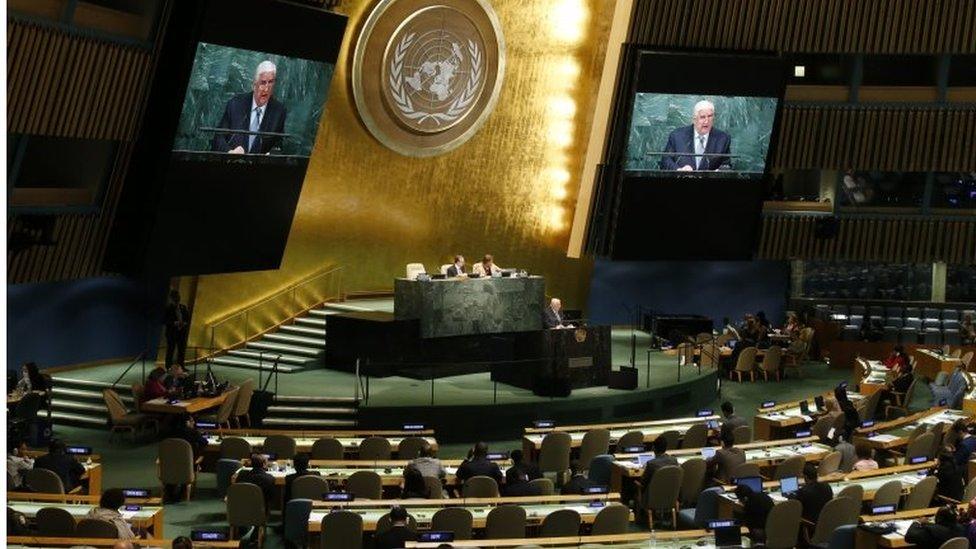

Antonio Guterres will become the next UN secretary general in early 2017

The United Nations, in the words of one diplomat I spoke to, is "broken and disheartened". So the task for the next Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, is to mend the organisation and give it some heart.

The outgoing incumbent, Ban Ki-moon, has been praised for his soft-spoken persistence in persuading the international community to do more on climate change.

Yet governments and diplomats have long wanted a secretary general with more clout, better English and, above all, stronger leadership.

So they have chosen not another foreign minister but - for the first time - a former head of government to be the ninth leader of the world's largest intergovernmental organisation.

Mr Guterres, 67, served as Portugal's socialist prime minister from 1995 to 2002, driving through the financial reforms that secured his country's membership of the European single market.

Alleviating the migrant crisis will be on Mr Guterres' to do list when he takes office in January

Many countries had wanted to choose a woman for the first time in the UN's history. Others, following UN traditions, said it was time for a candidate from Eastern Europe.

But in a process that was more transparent than usual, involving open hearings, it became clear to diplomats in New York that Mr Guterres was by far the best candidate - praising his credibility, his humanitarian track record and his ability to communicate.

Matthew Rycroft, the British ambassador to the UN, said: "What we are looking for is a strong secretary general.. who will take the United Nations to the next level in terms of leadership, and who will provide a convening power and a moral authority at a time when the world is divided on issues, above all like Syria.

"And I think that Antonio Guterres has demonstrated at the hearings and throughout this process that he is the person to do that."

Hard work ahead

But Mr Guterres will have a massive task ahead of him when he takes up the role in the New Year.

He will have to get the UN back into shape to face a deeply unstable world. As a former head of the UN refugee agency for the last decade, he will have the experience to tackle the migration crisis; the 65 million people who have been displaced across the world.

He will have to work out the UN's role in trying to bring stability to Syria when the Security Council is utterly divided on the conflict, with two permanent members - Russia and the United States - no longer even talking about a ceasefire.

Mr Guterres may be judged by his ability to reform the bureaucratic and unwieldy organisation

And he will have to work out the UN's role tackling terrorism and conflict elsewhere in the world often where the UN's 100,000 peacekeepers are struggling to keep any peace and human rights are often being abused.

The US ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power, said: "If we have these transnational threats and we don't have somebody at the helm of the United Nations that can mobilize coalitions, that can make the tools of this institution - creaky though they are, flawed though they are - work better for people, that's going to be more pain and more suffering and more dysfunction than we can afford."

For the Foreign Office in London, the key point is that a stronger, better-led United Nations would be better for the UK.

After the vote for Brexit, more of Britain's international influence - such that it is - will come through its permanent membership of the Security Council. And if the UN plays a bigger role, then so too will the UK.

But the expectations that will be placed on Mr Guterres' shoulders by both governments and global charities will be huge.

The UN director of Human Rights Watch, Louis Charbonneau, was blunt: "The next UN secretary general will be judged on his ability to stand up to the very powers that just selected him, whether on Syria, Yemen, South Sudan, the refugee crisis, climate change or any other problem that comes his way."

Others will judge him by his success in reforming a bureaucracy that has become so large and unwieldy that it has lost its ability to intervene effectively.

The first UN secretary general - a Norwegian politician called Trygve Lie - described his role as the most impossible job in the world. That was in 1945. And his statement is no less true today.

- Published6 October 2016

- Published5 October 2016