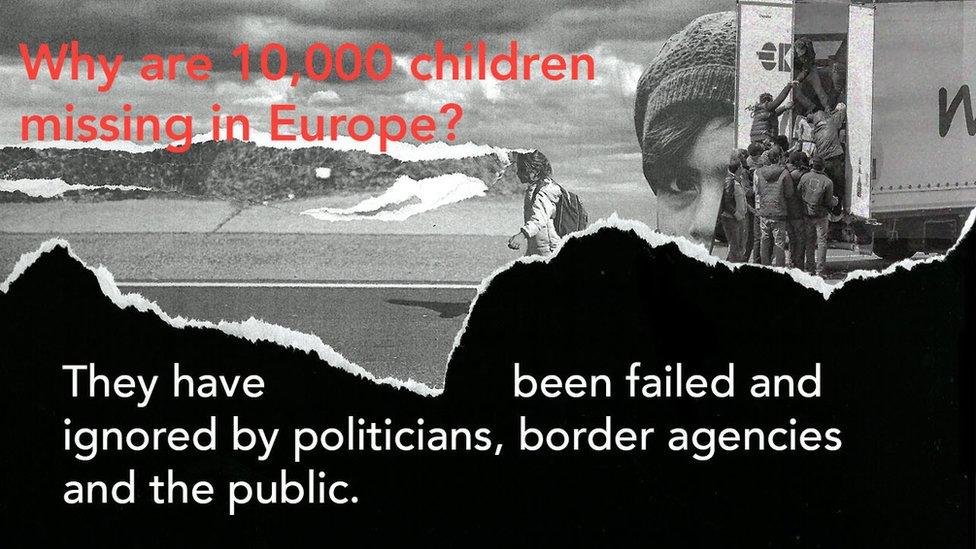

Why are 10,000 migrant children missing in Europe?

- Published

Europol, the EU's police intelligence unit, estimates that around 10,000 unaccompanied children have gone missing in Europe over the past two years. The BBC World Service Inquiry programme asks why so many have disappeared.

"There are different reasons [children] arrive unaccompanied," according to Delphine Moralis, secretary general of Missing Children Europe.

"Some of them have been sent by their parents hoping that their child would have a better chance at life, some of these children have been separated from their parents by smugglers as a way of controlling them, and some would have lost their parents in the chaos."

In 2015, according to Missing Children Europe, external, 91% of the children who arrived in Europe on their own were boys, and 51% were from Afghanistan.

Charities estimate there are about 1,000 unaccompanied children in the Calais "Jungle"

But the profile of these unaccompanied children is changing. More girls are arriving in Europe on their own, and the age of the children going missing is getting lower. Last year, for the first time, children as young as four went missing.

So what's happened to all these missing children? To put it simply, no-one really knows. That's because when a child from Syria, Afghanistan or Eritrea goes missing in Greece or Italy, nothing much happens. Few border agencies file a missing person's report.

There are concerns now that smugglers are turning the children they bring into Europe into the hands of traffickers to make more money. Those children might then be pushed into prostitution or slavery.

"Smugglers are exploiting the children that they bring into Europe," said Delphine Moralis. "The problem is that these children often turn to the people who got them into Europe, rather than to the authorities and that makes them vulnerable."

Gulwali Passarlay left Afghanistan aged 12, and it took him over a year to make it to Britain. He was separated from his brother almost immediately by the smugglers, so had to make the gruelling journey on his own.

He walked for days, hid in the back of lorries, jumped out of moving trains, and spent two weeks in an adult prison in Turkey before finally arriving on the Turkish coast. There, he was taken to a boat big enough for 20 people. There were 120 of them inside.

More and more youngsters are arriving in the EU on boats from the Middle East and Africa

"The boat broke down," he said. "This was the first time I'd seen the sea. I was terrified. I said to God, 'I don't want to die here. Not here in the Mediterranean. My Mum will never know whether I'm dead or alive'."

Minutes before the boat sank, the coastguard found them and took them to Greece. Gulwali was handed over to the police, then the army. His fingerprints were taken and then he was given the devastating news: he'd have to leave within a month or be deported.

By then he had found out his brother was in Britain, and so he did what thousands of other children have done. He left the refugee camp in Greece and disappeared.

"We'd walk through the railway lines so the police wouldn't see us," he said. "We kept a very low profile." Other children he knew went further to avoid being caught. They burnt their fingertips or cut them off entirely so that if they were found, they couldn't be identified and sent back home.

Eventually Gulwali made it to Calais where he made dozens of attempts to get to Britain. One day he got lucky: he crept into a lorry carrying bananas and made it into the UK.

The "Jungle" camp: The children trying to flee

It took Gulwali five years to get refugee status. He started school, went to university and, last year, wrote a book about his journey, The Lightless Sky.

But for every one who makes it, there are thousands who never get to this point. Like Gulwali, they feel safer disappearing than going through Europe's asylum system.

Ciara Smyth testified as an expert witness before the House of Lords EU Home Affairs Committee on the situation of unaccompanied minors in the EU, external. She also teaches law at the National University of Ireland Galway. She says the asylum system as it's set out in law does protect children, but that the laws aren't always followed.

"There are a number of EU agencies in hot spot areas in Italy and Greece that are supposed to identify asylum seekers, but they're turning into detention centres," she said. "When unaccompanied minors fester in camps, they're not going to tolerate that forever." And it's not only in Greece or Italy that children are struggling to enter the asylum system.

Home Secretary Amber Rudd said the UK was ready to act "with urgency" to help unaccompanied refugee children

Ciara Smyth says there's evidence that some European countries actively discourage children from applying for asylum because they want them to move on somewhere else.

"Many countries along the transit route to northern Europe adopt a 'wave through' approach where they're turning a blind eye to unaccompanied minors," she said. "They're not registering them. They're effectively encouraging them to keep going."

And they keep going because, like Gulwani, they're often looking for family members. And here, too, there's a gap between what should happen and what is happening.

Under the so-called Dublin regulation, external, when a child is first registered in a country, the authorities there should find out whether they have family in another EU state. If they do, the child should be sent there to have their asylum claim processed. But that rarely happens.

When children do eventually arrive in a country where they want to claim asylum, a representative should be appointed to support them through the asylum process. But according to Ciara Smyth, while some countries have good guardian services, in others, there are none.

Remember, these children are often completely on their own. And when their asylum claims are being processed, they often have to undergo humiliating physical tests - teeth X-rays, head measurements or bone density exams to check they're not lying about their age. Then they have to explain why they left home. They'll be interviewed repeatedly and asked to recount, in intricate detail, the traumas they've escaped from.

"Very often unaccompanied minors might not have a very clear recollection of events," she says. "It's very difficult for them to give a linear narrative. Successful asylum claims are all about being able to present a coherent story."

Find out more

The Inquiry is on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays

You can listen online, or download the programme podcast

At that point, more children disappear. So why isn't more being done to support these vulnerable children?

Last year, almost 90,000 unaccompanied children arrived in Europe. That's a huge number. Clearly, even if every EU state devoted more attention and resources to the problem, child migrants and refugees would continue to slip through the net. Looking after children who are already within the asylum system has placed a huge strain on local authorities, at a time when budgets are already under pressure.

But according to Ciara Smyth, the EU is failing to adhere to the very policies it created to protect children. And it seems that the public, too, are turning a blind eye.

A year ago, after the photograph of the drowned toddler Alan Kurdi was published, people all over Europe became more sympathetic towards child migrants and refugees. People welcomed them into their homes, donated food and even volunteered in the Calais camps.

Indian artist Sudarsan Pattnaik created a sand sculpture of the image of Alan Kurdi's body

Britain, Germany and Canada all said they would accept more refugees and European leaders agreed to share responsibility for refugees arriving in Greece and Italy.

One year on and many of those promises have been broken. Yet there's been little public outcry. Why?

It's partly about economics. As austerity bites across Europe, people feel less inclined to help outsiders. And the alleged connection between migrants and militants hasn't helped. Without popular support, politicians are less inclined to take action and enforce the rules that exist to protect children.

So the story of the 10,000 missing children tells a much broader one about failure: the failure of border authorities to follow laws which exist to protect children and the failure of Europeans - moved by that photograph of Alan Kurdi - to continue to care for long enough to persuade political leaders to keep the promises they made.

- Published10 October 2016

- Published9 October 2016

- Published4 October 2016

- Published1 October 2016

- Published30 September 2016

- Published31 January 2016