Hollande's Le Monde interviews 'political suicide'

- Published

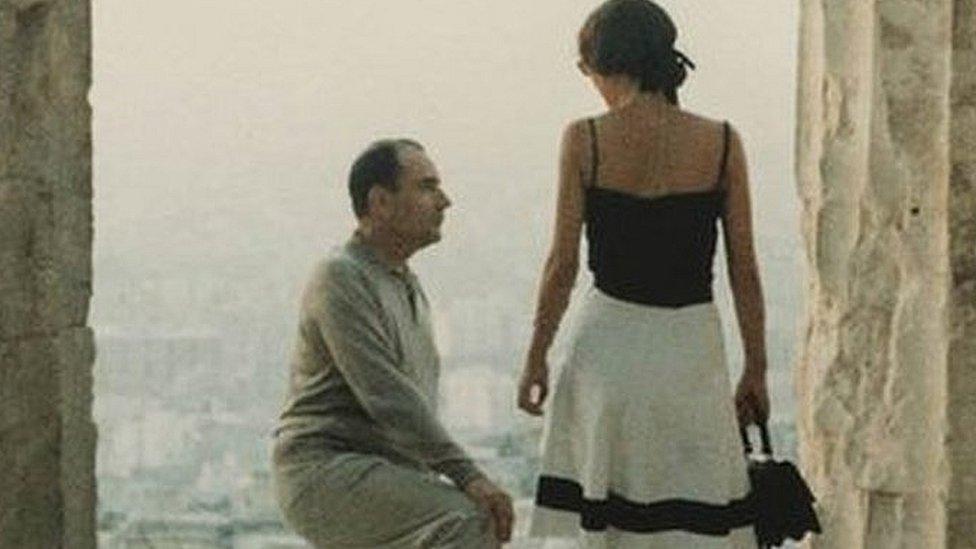

The president's friends fear the revelations will undermine his ambition of winning a second term in office

What kind of candidate, a few months ahead of elections, takes it on himself to offend a list of people that includes judges and lawyers, immigrants and Muslims, footballers and intellectuals, political allies as well as enemies, the intelligence community and his ex-girlfriend too?

The answer is Francois Hollande.

In a collection of interviews just published by two Le Monde journalists, the French president unburdens himself, in astonishingly cavalier style, of a series of revealing jibes:

The justice system is full of "cowards"

There are "too many" immigrants

There is a "problem" with Islam

Footballers need "brain-building"

Intellectuals are "not very interested in the idea of France"

There's more. Presidential predecessor and Republican candidate Nicolas Sarkozy is a "crude mini-De Gaulle" and a "Duracell rabbit". The Greens are a "cynical pain in the butt" and left-wing rebels are a "crowd of idiots".

Among those criticised by the president are ex-partner Valerie Trierweiler and political rival Nicolas Sarkozy

And, on a personal note, ex-partner Valerie Trierweiler was a traitor because she lied about his famous "toothless" quote about the poor.

Perhaps most damaging of all, not a jibe but a revelation: the admission that he personally ordered the assassination of four enemies of the state, presumably militants in the Middle East. The secret services must be fuming.

Friends in the Socialist Party, still hoping Mr Hollande might have a decent shot at a second term in April, are flabbergasted at the president's verbal carelessness. They fear it has already undermined his nascent campaign.

Others are more blunt. For more than one commentator, the book - called appropriately A President Should Not Say That - is little less than an act of "political suicide".

"How do you manage to turn your camp into a field of ruins, fill your friends with despair and your enemies with rejoicing, and weaken your own position just a little bit more?" asked Le Monde, external.

"Francois Hollande has found the recipe."

What was he thinking?

The interviews, 60 in all, were accumulated over the last five years by Gerard Davet and Fabrice Lhomme.

The president received them regularly at the Elysee Palace and they chatted. The journalists made no secret of their intention of writing a book, and Mr Hollande agreed to their condition of no copy-vetting.

In his defence, it has been argued that the controversial comments were made a long time ago - and it is easy to take things out of context.

Francois Hollande came to power with the promise to be a "normal" president

All he was trying to do, plead the president's dwindling band of loyalists, was keep his promise of being a "normal" president by opening his doors, as well as his thoughts, to the press.

But, off the record, many Socialists are exasperated by what they see as a kind of narcissistic self-indulgence on the part of their leader.

What psychological impulse can it be, they ask, that made him spend so much time baring himself to journalists? How could he have been so naive?

More from Hugh:

With the book selling out in shops across Paris, the damage is already visible.

In a poll, 78% of those surveyed said it was a mistake for Mr Hollande to give the interviews. An even greater figure, 86%, said they did not want him to run for a second term.

Until now Mr Hollande has kept his career options open.

A Socialist primary will be held in January, and the president will announce if he is a candidate only after the centre-right holds its primary next month.

The consensus until this week was that the president would indeed run again, despite record unpopularity and the failure of his solemn vow to bring down unemployment.

The argument, as ever with Mr Hollande, is that only a bridge-builder like himself can bring together the two competing wings of the Socialists. The existence of rival candidates - Arnaud Montebourg on the left, Emmanuel Macron on the right - tends to reinforce that case.

But now more and more people in the party are pondering whether the president might not be an outright liability.

"It's bewildering. I lack the words to say what I think: something between a hammer-blow to the head, and the straw that broke the camel's back," one Socialist MP told Le Monde after reading extracts from the book.

"Imagine burying your grandmother when she is still alive; that's roughly the ambience at party HQ," said another.

Hitting back at Hollande

The president's unguarded quips have already led to a series of angry rejoinders from his targets.

The footballers' union pointed out that President Hollande had frequently met the national team

Magistrates said they were "stupefied" by his criticism, and the Union of Professional Football Players said, external: "Sorry to disappoint you, but not all of us are thick."

Mr Hollande's ex-partner Valerie Trierweiler sent out a tweet, external to contradict his denial that he had mockingly called the poor "toothless". In the book Mr Hollande says that her original accusation to that effect, made after the pair had split, was an "odious act of treachery".

For many commentators, the interviews are symptomatic of his original mistake when he defined himself as a "normal" president in contrast with the frantic "hyper-president" Nicolas Sarkozy.

As political scientist Gerard Grunberg pointed out, in such abnormal times, France was not looking for a normal president.

- Published1 June 2016

- Published13 October 2016

- Published29 September 2016