The Russians who fear a war with the West

- Published

In a bit of woodland on the outskirts of Moscow, several dozen students are running around in combat fatigues, shooting one another with soft air-gun pellets.

The weekend paintballing trip has been organised by an opposition party. It all looks harmless enough. But in Russia, not everything is always as it seems.

"We offer a wide range of military-aligned subjects," Stepan Zotov tells me. He's the party activist running the event.

"It's knife combat, knife throwing. Also live ammunition, so we go to shooting ranges or sometimes to military encampments."

Mr Zotov's party, Rodina, which means Motherland, is part of what is known as the "loyal opposition", meaning that it supports the Kremlin.

And his activities are part of a government-supported programme of "military-patriotic education" for students.

Russian TV recently broadcast pictures of a civil defence exercise

I've come to see Mr Zotov because, watching Russian television in the past few weeks, you might think that the country was heading for a military confrontation with the West.

Earlier this month, one state-controlled news programme told its viewers to find their nearest nuclear bomb shelter before it's too late. Russia recently conducted nationwide exercises to prepare for just such an eventuality. Mr Zotov is taking this seriously.

"We are preparing for a confrontation with the West. But mostly this confrontation happens on the cultural, informational and value level. Russian civilisation is a culture of heroes and warriors."

Mr Zotov remembers the collapse of the Soviet Union not as a triumph of freedom but as a tragedy.

"Our great country dissolved without warfare, without open conflict. Because we started to love a different people and a different culture, not our own."

Stepan Zotov tells me he has fought as a volunteer alongside separatist forces in eastern Ukraine.

Watch Gabriel Gatehouse's full report for BBC Newsnight

"Me and my comrades, and unfortunately some of my cadets have already taken part. It is a conflict between Russia and the West."

None of the students I speak to seem interested in volunteering to fight in Ukraine. They are in their late teens or early 20s, all of them born in the post-Soviet period. And they seem unconvinced by the talk on TV of a looming conflict.

"You shouldn't watch TV in Russia," one young woman says.

"The media is whipping things up. This is an information war. You shouldn't pay attention to it. They're making the people anxious for no reason."

I ask them what the concept of the West means to them.

"Capitalism," says one.

"Opportunity," says another.

President Putin is now confronting US President Obama on a host of issues

"Also the culture is interesting. It's a different culture. Maybe one day there will be co-operation because we all live on the same planet and there's no sense in war."

Almost as soon as he came to power, Putin began taking control of Russia's TV stations. That process is now complete. What you see on television today is either sanctioned by or sympathetic to the Kremlin.

News programmes serve up a diet of stories about war and crisis abroad, and of international double standards. The Ukrainian government has been accused of crucifying babies; the BBC of staging a chemical attack in Syria.

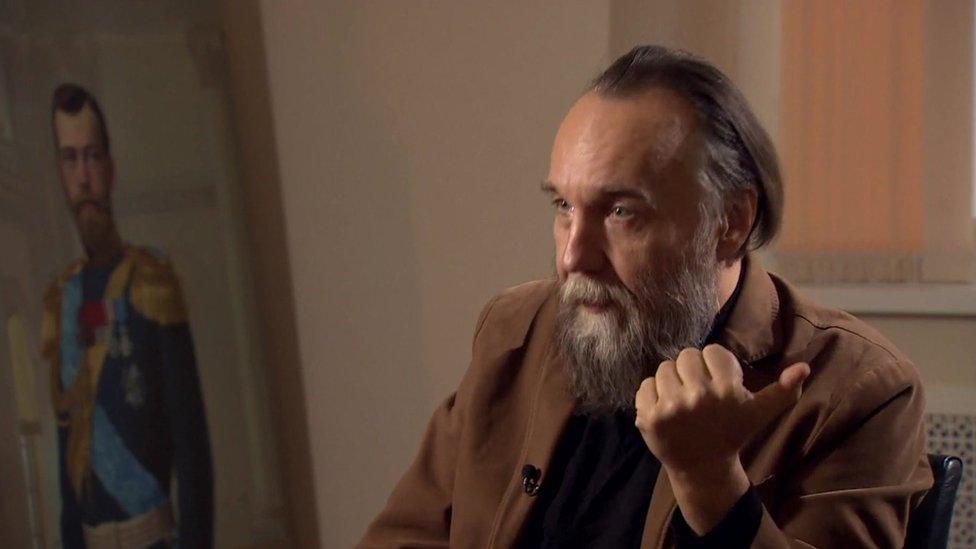

Truth has become subordinate to political expediency. To support this difficult balancing act, a philosophical framework has been constructed. One of its chief architects is Alexander Dugin, a thinker and ideologue, who is under US sanctions for his alleged involvement in Russia's annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine.

Alexander Dugin argues that the truth is a question of belief

"The truth is a question of belief," he told me, when I visited him at his own religiously oriented TV station near the Kremlin.

"Post-modernity shows that every so-called truth is a matter of believing. So we believe in what we do, we believe in what we say. And that is the only way to define the truth. So we have our special Russian truth that you need to accept."

Dugin's philosophy is known as Eurasianism. It holds that Orthodox Russia is neither East nor West, but a separate and unique civilisation, a civilisation engaged in a battle for its rightful place among world powers. His work has become increasingly influential among Russia's political and military elite.

"If the United States does not want to start a war, you should recognise that United States is not any more a unique master. And [with] the situation in Syria and Ukraine, Russia says, 'No you are not any more the boss.' That is the question of who rules the world. Only war could decide really."

Mr Dugin's bellicose doublethink is not aimed solely at the West. There is a message for internal consumption too. It is this: there is no such thing as universal liberal values; there is no inherent contradiction in a democracy that allows no dissent.

Opposition politician Boris Nemtsov was killed last year

In the shadow of the walls of the Kremlin, Russia's dwindling band of activists keep alive the memory of Boris Nemtsov, laying flowers on the spot where the opposition politician was gunned down last year. It's cold and lonely work.

"I still believe that truth exists," says Mikhail Shneider, a former Soviet dissident and comrade of Mr Nemtsov.

"It is a fact that they killed Boris Nemtsov right here, 10m from where we're standing. It is a fact that Putin is in the Kremlin. It is a fact that Putin's TV lies."

Most Russians don't really believe that nuclear war with the West is coming. Perhaps their leaders don't believe it either. They probably don't really believe in the post-modern Orwellian state.

But the more a lie is repeated, the more it risks morphing into some sort of reality.

- Published21 October 2016

- Published19 October 2016

- Published17 October 2016