Is Turkey still a democracy?

- Published

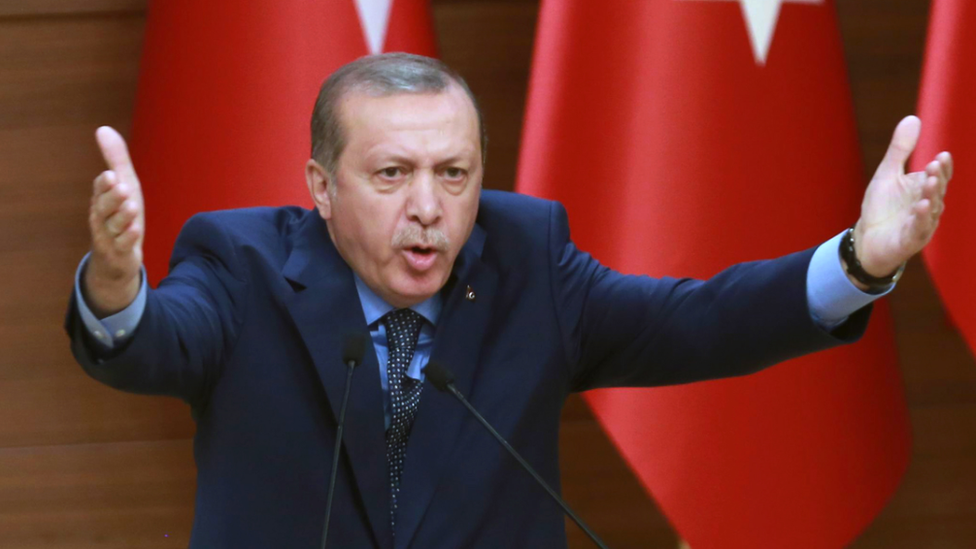

Since an attempted coup in July, Turkey's President Erdogan (centre) has placed tens of thousands under arrest

What has happened to Turkey? Four years ago, it was held up by the West as a model for the Muslim world: a democracy (albeit flawed) that was negotiating EU membership and advancing towards a peace settlement with its Kurdish minority.

It was seen as an anchor of stability in the volatile Middle East - although critics here believe the perception from outside was already skewed.

This week, the World Justice Project's rule of law index placed Turkey 99th of 113 countries, just behind Iran and Myanmar. It has reclaimed its place as the world's main jailer of journalists. A couple of analysts who I asked to interview for this piece were unwilling to be quoted, for fear of speaking out.

"It is the end of democracy", the HDP's Deputy President Hisyar Ozsoy told the BBC.

"We didn't have much democracy anyway, but even the very limited democratic space is totally wiped out".

Protestors read the Turkish daily newspaper Cumhuriyet after police detained its editor

Consider what has happened in the past week:

The co-mayors of the largest Kurdish-majority city, Diyarbakir, were arrested for alleged links to the PKK Kurdish militants, which Turkey and the West label a terrorist group.

Another 10,000 civil servants were dismissed, charged with supporting Fethullah Gulen, the US-based cleric whom the government believes masterminded the failed coup. This takes the number of suspended or dismissed public servants since July to 100,000.

A further 137 academics in Ankara were served with an arrest warrant for alleged Gulen links. Some 37,000 people have now been arrested since July.

The law was changed to allow President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to choose university rectors, instead of academics electing a candidate.

Fifteen more media outlets were closed. Around 170 have been shut since July.

The editor, cartoonist, and other staff at Turkey's oldest mainstream newspaper, Cumhuriyet, were arrested on charges of supporting the PKK and Fethullah Gulen. Cumhuriyet is a bastion of secularism that has regularly condemned Kurdish militancy and the Islamist Gulen movement.

The leaders and several MPs of Turkey's third largest political party, the pro-Kurdish HDP, were arrested for alleged links to the PKK. Party supporters say it's an attempt to push the HDP out of parliament and increase Mr Erdogan's power. Hours later, a car bomb killed nine people in Diyarbakir. The government blamed the PKK, but the so-called Islamic State issued a questionable claim of responsibility.

The government cut the internet to southeast Turkey and "throttled" services such as WhatsApp, Twitter and private networks (VPNs) across the country, slowing them down to make them unusable.

The Turkish lira plummeted to a record low against the US dollar.

After criticism from the EU, with the head of the European Parliament saying Turkey had "crossed a red line", the prime minister hit back with, "Brother, we don't care about your red line… we draw another red line on top of yours", and the president accused Germany of harbouring terrorists.

Tyrant or saviour?

Is Turkey still a democracy? As ever, it depends on which side you speak to in this polarised country. The victims of the post-coup purge, leftists, secularists and Erdogan critics believe democracy here died some time ago as the president, shaken by challenges, expelled or sued opponents and fell back on a close circle of ultra loyalists.

President Erdogan is a hero to some, and a monster to others

But the other half of the country - and it is split almost evenly in two - revere a man they believe has transformed Turkey for the better and is misunderstood by the outside world. They feel the level of Turkey's threat from terrorism - from the PKK, 'Gulenists' and its geographical misfortune of bordering Iraq and Syria - is not appreciated by the West.

All politicians are corrupt, goes the argument, but at least this President gave the pious side of the country equality, built hospitals and schools, and is the big leader that Turks crave.

More from Turkey:

The night of 15 July is held up by the government and its supporters as a sign of Turkey's democratic maturity: when more than 240 people were killed on the streets resisting the tanks and coup-plotters, blocking the fifth military takeover in Turkey's history and stating loudly that Turks will choose their leaders at the ballot box rather than at gunpoint.

But the kind of democracy that was defended that night is still heavily contested. Unity against the coup did not equal unity in favour of this government. Elections are still relatively free here, but not fair. The governing AK party hugely dominates the media, and is accused of intimidating voters.

Kurdish demonstrators with banners protest against Turkish policies in Frankfurt am Main, Germany

There are a (decreasing) handful of non-government supporting media. And Turkey remains a vital member of NATO, although its relationship with the US is increasingly fractious over Washington's support for the Syrian Kurds fighting IS, and it has been excluded from the coalition offensive on Mosul because of strained ties with Baghdad.

Turkey is the vital partner the West can't afford to drop. But when it comes to visions of democracy, there are two realities in Turkey - each side has its own narrative. And increasingly, never the twain shall meet.

- Published5 November 2016

- Published4 November 2016

- Published13 October 2016