The Collins brothers: Waterford tribute to tragic WW1 family

- Published

The Collins brothers were from a large, working-class Catholic family who lived in the heart of Waterford city when World War One broke out in 1914

It sounds like the plot of a Hollywood movie - a family of young brothers all go off to war to fight until all but one of them is missing, presumed dead.

The last surviving soldier is sent home on compassionate leave to comfort their devastated mother.

It could be the storyline of the 1998 Oscar-winning film, Saving Private Ryan, but it is also the true story of an Irish family from County Waterford.

A century on, they have been honoured by their home city for the first time.

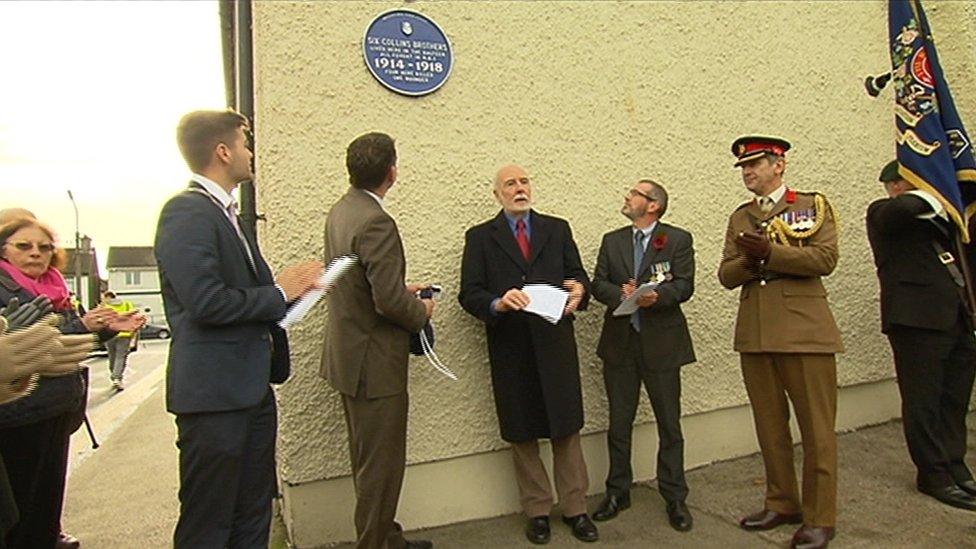

Irish politicians, members of the Royal British Legion, and relatives of the brothers attended a memorial ceremony in Waterford city on Saturday, during which a blue plaque was unveiled at the family's former home.

The Collins family said Irish recognition of the brothers' sacrifice was very important to them

The Collins brothers were from a large, working-class Catholic family who lived in the heart of the city when World War One broke out in 1914.

Six of the oldest brothers signed up to fight with the British Army, volunteering for service as there was no conscription in pre-partition Ireland.

Four of the six soldiers were killed in battle on various dates from 1914 to 1918 - the youngest to die was just 16 years old.

When their grieving mother received a telegram to say that a fifth son was missing, presumed dead, the sixth soldier was sent back to her in Waterford.

By then, their father had left and she was left to bring up her younger children alone.

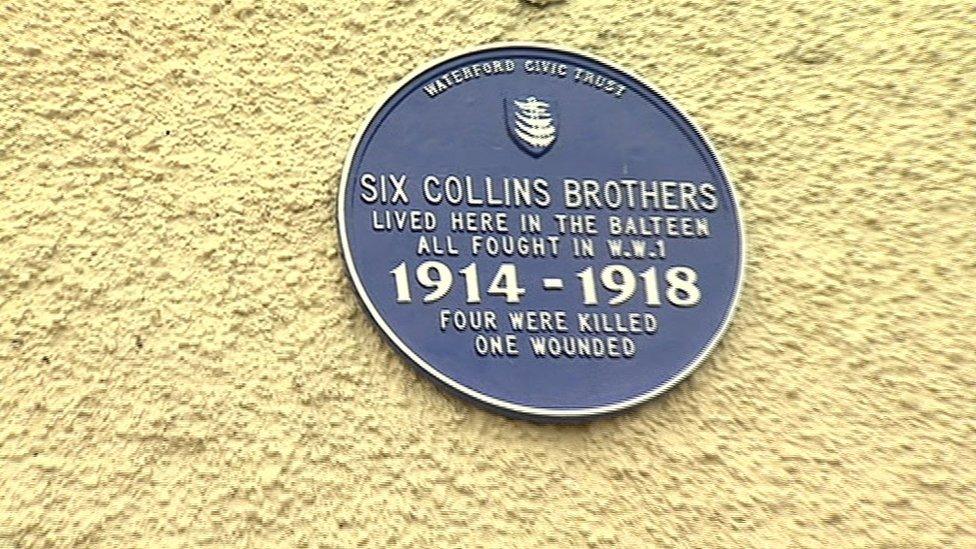

The plaque was unveiled by the Waterford Civic Trust on Saturday

Months later, the missing brother was found badly injured in a convent hospital in France.

He was brought back to Ireland after the war, but never fully recovered from his wounds, and is said to have spent the rest of his life in pain.

To add to their troubles, the Ireland that the two surviving sons came home to had changed utterly following the 1916 Easter Rising, and was on the brink of the War of Independence.

'Traitors'

Fighting for the British Army was suddenly viewed as a betrayal, and Irish veterans did not openly discuss their role in World War One.

The stigma was so great that many of their descendants had no idea of the extent of their own family's suffering and sacrifice.

"My grandfather was William Collins - he was the sixth brother who was sent home when his mother received five telegrams to say that they were missing in action," Pat Collins told BBC News NI.

Pat was not even aware that so many of his relatives had fought and died in WW1 until about five years ago, when the Collins family began to research William's military records.

Among William's possessions, they found an Army book which contained the service numbers of the brothers he lost in the war, which enabled the family to trace their story in full using military archives in England.

"But up until that time, nobody in the family knew much about what happened, because I know my grandfather never spoke about it to anybody", Pat said.

"If you fought in the First World War, you were seen as pro-British and at that time - with the political situation - they were looked on basically like they were traitors."

Irish politicians, members of the Royal British Legion, and relatives of the brothers attended the memorial ceremony in Waterford city on Saturday

In 2014, a delegation of the Collins family travelled to France and Belgium to visit the four brothers' memorials, which consist only of names inscribed on monuments, as none of their bodies were ever recovered.

'Far-fetched'

That same year, Pat's daughter, Rachel Collins, who works for the Irish Times, wrote an article about her family's discovery, external.

"I've never watched Saving Private Ryan. An aversion to violence, bloodshed and the sad inevitability of war films means I haven't seen the epic 27-minute opening scene, where Tom Hanks and his comrades face the carnage of the Normandy landings," she wrote.

"Besides, the plot has always seemed a bit far-fetched. A family of boys wiped out by war; an army that was only too happy to send its sons to slaughter suddenly pulling out all the stops to save the last remaining brother.

"Then earlier this year while talking to my father, I learned that not only was such a story entirely plausible, it had played out in our family."

Rachel outlined how the youngest casualty, 16-year-old Stephen Collins, was the first to die on the battlefields of WW1.

Stephen was underage when he joined the Royal Irish Regiment, and was killed in Flanders in October 1914, less than two month after the war began.

The following year, his 24-year brother Michael Collins - a namesake of a much more famous Irish soldier - was also killed in Flanders with the same regiment.

In September 1916, 22-year-old John Collins lost his life at the Battle of the Somme, fighting with the Royal Munster Fusiliers.

The eldest son, 30-year-old Patrick Collins fought for four years, and was the last to die in March 1918. The Royal Engineer is also commemorated at the Somme.

'Reconciliation''

On Saturday, the entire family's tragic story was commemorated by the people of their home city for the first time.

The Waterford Civic Trust unveiled a plaque at the brothers' family home while politicians, including representatives of Sinn Féin, joined members of the British Legion at a church ceremony.

Relatives and descendants of the brothers had campaigned for recognition in their home city

Sinn Féin's Jim Griffin attended the event in his capacity as Waterford's metropolitan deputy mayor and told BBC News NI he had "no problem" taking part.

He said many young Irishmen joined the British Army out of "necessity" in 1914, to provide for their families, and were not aware of what lay ahead of them.

As an Irish republican, he said he recognised that reconciliation and integration was needed, and that things have to "move on".

"If Martin McGuiness can sit and have dinner with the Queen, I can go to an event like this," he said.