Le Pen stalks French centre-right presidential contest

- Published

There were forced smiles and finger-jabbing as the candidates sparred in TV debates ahead of Sunday's primary vote

Security, French identity, labour reforms and the price of a pain au chocolat - these issues will guide supporters of France's centre-right Republicans when they choose a presidential candidate on Sunday, Becky Branford reports.

So far, so everyday - but behind the finger-jabbing, fake smiles and odd excruciating faux-pas lurks far-right National Front (FN) leader Marine Le Pen.

With France's left in disarray, the winner of the vote may be the only obstacle to her sweeping to power.

In what analysts say is a response to Ms Le Pen, for the first time the candidate of the Republicans will be chosen in US-style primaries - two rounds of voting on 20 and 27 November.

Seven candidates will be whittled down to one, who will then face rivals from other parties, in France's two-round presidential vote in April and May.

What's Marine Le Pen got to do with these primaries?

On the surface, nothing.

The Republicans are not blazing a trail here. The Socialists introduced primaries in 2011, ahead of the 2012 election.

Both parties say primaries increase transparency in the selection process, broaden participation and, through the TV debates that precede voting and offer equal coverage of all candidates, level the playing field. Potentially they give new faces a chance.

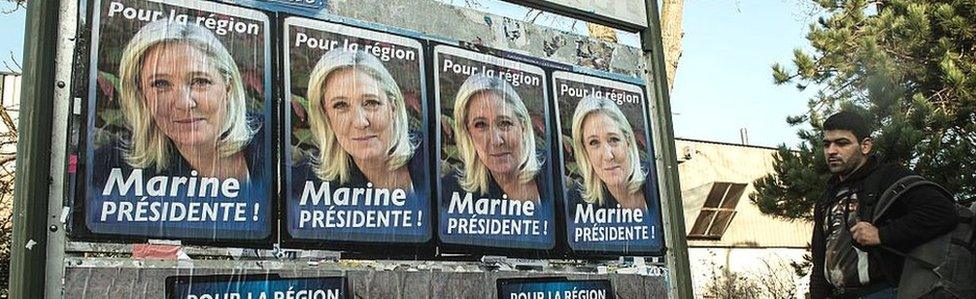

Political calculations are taking place on how best to contain the threat posed by Marine Le Pen's FN party

But these primaries are a tacit response to the growing popularity of Ms Le Pen, say analysts.

Her FN took 27% of the vote in regional elections last December. The Economist estimates Ms Le Pen could have a 40% chance, external of becoming France's next president. Prime Minister Manuel Valls highlighted this "danger" on Thursday.

By enabling the Republicans to rally around a single candidate well ahead of the election, the primaries may reduce the risk of Ms Le Pen exploiting rivalries among her opponents.

The Republicans' vote is open to anyone who pays €2 (£1.70 $2.15) and signs up to a statement of centre-right values.

Rather than new faces, I see a lot of familiar ones here...

Well, yes - well-known, and not universally loved.

Nicolas Sarkozy was a polarising figure as French president in 2007-2012

Probably the most divisive figure in the running is former President Nicolas Sarkozy, who has come back from his 2012 defeat to the Socialists' Francois Hollande. He has faced claims of wrongdoing such as illegal party financing, which he denies - but the claims have not yet been put to bed.

Just this week, he furiously denied a Franco-Lebanese businessman's claims that he delivered three suitcases stuffed with cash from the Libyan regime to help Mr Sarkozy's first presidential bid.

Alain Juppe is also a familiar figure as Bordeaux's mayor, who also served as prime minister from 1995-97.

Opinion polls have consistently put Alain Juppe in the lead for the nomination

Not only were Mr Juppe's welfare reforms at the time defeated by street protests, but he was actually found guilty of illegal party financing, earning a 14-month suspended jail term and temporary ban from public office.

He was once nicknamed "Amstrad" for his cold, computer-like image.

Until recent days, polls had Mr Juppe as favourite, but the race has narrowed and it's now impossible to call between Mr Juppe, Mr Sarkozy, and Francois Fillon, who has enjoyed a late surge.

Free-market fan Francois Fillon (left) has made a late challenge to Mr Sarkozy for a place in the 27 November runoff vote

Mr Fillon is considered to be an economic liberal. Although he was Mr Sarkozy's PM for five years, he does not share the socially hardline stance of the former president.

He is well known to fellow candidates Bruno Le Maire, 46, who served as junior minister under him, and Jean-Francois Cope, whom he once fought for the leadership of the party.

Ms Kosciusko-Morizet worked in Mr Sarkozy's government but now says she saw how he operated "close-up"

Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet (known as NKM) served as a minister under Mr Sarkozy, and later became his spokeswoman.

Probably the least-known candidate is Jean-Frederic Poisson.

How has the fight played out?

The central issue preoccupying spectators has been whether, in a climate of fear following last November's jihadist attacks in Paris, Mr Sarkozy can steal the nomination with his hardline stance on Islam and security.

He wants to extend the school ban on Muslim girls wearing the hijab (headscarf) to universities, and recently insisted immigrants must accept their ancestors "are the Gauls".

Mr Juppe, by contrast, has struck a softer tone, captured in his talk of France's "happy identity".

In many areas, of course, the conservative candidates share common ground. Despite his "happy" talk, Mr Juppe shares with his rivals a zeal for reform - scrapping the limit on weekly working hours, raising the pension age and cutting the civil service.

A key point of concern is how far the Republicans should reach to try to capture voters tempted by the far right. That anxiety was captured by Ms Kosciusko-Morizet in a TV debate on 3 November, when she said of Mr Sarkozy: "There is a risk that this campaign is polluted by the FN. One must not borrow themes from the National Front."

The contest may also have been affected by Wednesday's announcement that former Socialist and self-declared centrist Emmanuel Macron will run for the presidency as an independent - potentially posing more of a threat to a Juppe candidacy than a Sarkozy one.

What they said:

"About 10 to 15 centimes?" Jean-Francois Cope estimates the price of a pain au chocolat - which actually costs something like 10 times that. He blamed his calorie-counting for putting him out of touch, but the internet laughed.

"If you like, we can go [shopping] together, you'll see that I live in the real world and that I wait in the queue at the check-out." Alain Juppe tries to extricate himself from similar suggestions he was detached from daily life, after making a contemporary reference to the long-defunct Prisunic supermarket chain.

"Exactly. I saw it close up and now I'm a candidate against you." Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet recoils at being patronised, in her view, by Mr Sarkozy when he said she had been a "very good spokeswoman" for him, in a TV debate.

"A double ration of fries, that's the Republic." Mr Sarkozy wades into a row over whether schools should offer alternative options for those - including Muslims - who are unable to eat foods such as pork. He said schools should refuse to do so. "Voila, the mini-Trumps proliferate," was the response, external of Paris-based The New Yorker writer Lauren Collins.