Can a Syrian cafe hold the key to the German migrant crisis?

- Published

The Royal Cafe is staffed by refugees from the Red Cross camp in Oberhausen

Hassan Al Babi, a Syrian refugee from Damascus, is steadily carving slices of chicken shawarma off a gas-heated rotisserie. It's lunchtime in Oberhausen and the German city's first Syrian restaurant is doing a brisk trade.

"It's not about the job as such," says Hassan.

"It's about the fact that I'm working and producing and not waiting for help at the job centre."

In the year since BBC News first visited Oberhausen, refugees have started to become part of the community.

More than 2,500 refugees, many fleeing conflict in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan, are currently settled in the city.

Hassan Al Babi says working in the cafe is better than queuing in the job centre

The Royal Cafe opened in August this year. The €30,000 (£25,000; $32,000) start-up cost was covered by German-Palestinian, Omallah ali Maher.

The café is managed by Mr Al Babi and another Syrian friend. It employs a further three Syrian refugees to serve its customers. Mr Ali Maher met them at the Red Cross camp in Oberhausen.

"They told me that they wanted to work for themselves. They don't want to be beggars," he said.

How a former migrant has helped finance a cafe providing work for five new Syrian refugees

"We don't have a written contract. I just looked in their eyes I see they are really honourable people."

All profits made by the business go towards paying the staff and paying back their debt.

According to Mr Ali Maher, who helps the men by collecting supplies and doing their German paperwork, the café's model of using business to help refugees is the answer to Europe's migrant crisis.

"We can be successful by solving the refugee problem in Germany, when we get people to work," he says.

"I am 71 years old, I feel like 60 and I work from morning until the evening but I feel happy because I am doing a kind of nice work for those people and their families."

Café Royal's success is a positive reflection of how refugees are adapting to life in Oberhausen.

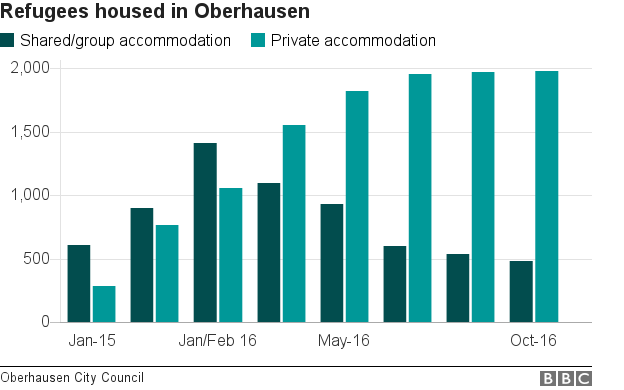

The city's new arrivals have now been moved from shared accommodation - blocks of flats used to house groups of migrants - and most are now in state-provided flats around the city.

"I think we are on top of the situation completely," says Joerg Fischer of the German Red Cross.

"Now a system is in place and is working well. Around 40 refugees arrive every week. This is nothing compared to last year when we had up to 300 a week. So we can manage this and the integration of those who've been here for longer."

Oberhausen lies in the western state of North Rhine-Westphalia, which took in 172,511 asylum-seekers in the first 10 months of 2016.

That is almost 27% of the total number of people seeking asylum in Germany over that period, and more than double the number of the region with the next highest number of refugees, Baden Wuerttemberg.

A BBC team first visited a year ago and returned last spring to speak to aid workers, residents and the asylum seekers themselves.

How one German city is coping with migrant crisis - BBC visits Oberhausen in November 2015

Changing attitudes of a German city - BBC visits Oberhausen in April 2016

Settling into school

Svenja Beyer says it's easier to cope with just 12 pupils in her class

In April this year Svenja Beyer's integration school in Oberhausen was struggling with a class made up of 34 pupils from nine different countries.

There were problems with aggressive behaviour and fights between different ethnic groups.

But now some of the older pupils have moved on to other schools and the number of pupils in her class has fallen to 12, although still of several different nationalities.

"We have a different atmosphere now. It's calm, it's peaceful," she says. "The pupils are motivated and they learn very rapidly, they want to learn and so fewer children means more time for every child."

For adults there are numerous state-run and non-governmental group initiatives aimed at helping them find work.

But one that has made headlines is Serap Tanis's women's empowerment group, the Courage Project. The local group aims to help newly arrived immigrants and refugees realise their potential while living in Germany.

Ms Tanis, the project leader, is herself an immigrant of Turkish descent. She moved to Germany from Istanbul when she was six years old. She compares herself to a pearl diver, believing that "there is a 'treasure in everyone hidden deep below".

Through discussion groups she helps women to think about education and employment in a new light. However, Ms Tanis is keen to stress she's not trying to turn them into Germans or transform them overnight.

"Empowerment is a process and we give them the courage to find their strength," she says.

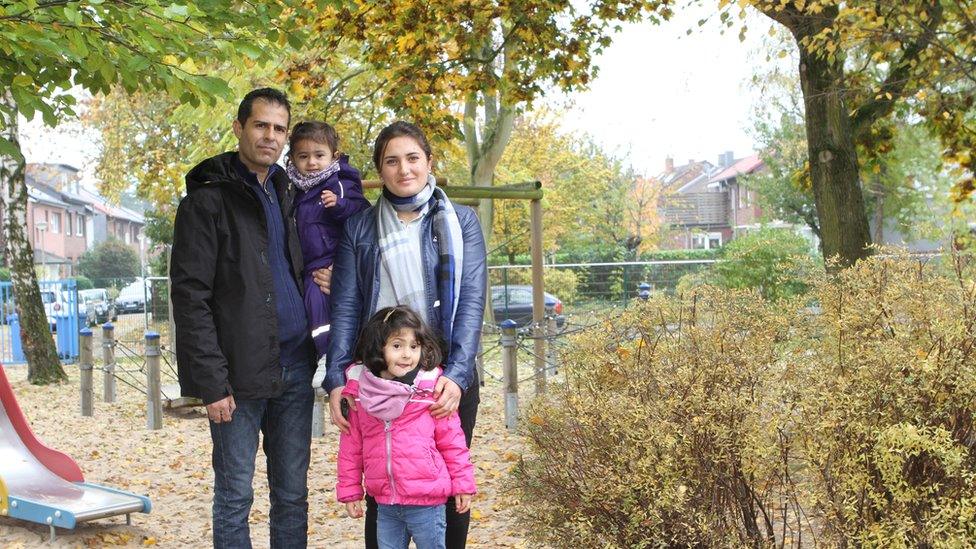

Roudin Davo and her family arrived in April

One of the women she is helping is Roudin Davo, a Syrian Kurd who fled from Kobane in Northern Syria after jihadist group Islamic State captured the city in October 2014.

She arrived in Oberhausen in April 2016 after a treacherous journey through Europe with her husband and two young daughters.

"We lost everything, but here we try to begin again from the bottom," says Mrs Davo.

"Before [in Syria] I thought: I am a mother, I have to stay at home. But then my friends told me there is a school where they look after my girls and I can learn German."

It's difficult to know whether schemes like the Courage Project have helped refugees into work, but unemployment in Oberhausen has fallen this year from 11.7% in March to 10.3% in October.

That is still far higher than the 6% average across Germany.

Far-right demonstrators meet opposition in Oberhausen from supporters of the migrants

When BBC News last visited Oberhausen in April its Chief Police Inspector Tom Litges said there was a sense of fear towards refugees among some of Oberhausen's residents following the New Year's Eve sex attacks in nearby Cologne.

Some of Oberhausen's residents even began calling for civil patrols. But nothing ever came of it and the fear has dissipated.

"There haven't been any serious crimes related to migrants in the last six months," says Chief Inspector Litges.

But right-wing activists have been targeting the city. Since April, there have been two anti-immigration rallies - made up of about 70 far-right protestors, mainly from neighbouring Essen.

The right-wing nationalist party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), has been growing in popularity since it started in 2013 and now has MPs in nine of Germany's 16 state parliaments - although none in North Rhine-Westphalia.

"Every now and then what we do have is [right-wing] demonstrations and usually those who are against the right-wing demonstrators are normally five, six, seven times more [in number], says Chief Inspector Litges.

"So for that reason the people of Oberhausen show that they do not accept right-wing propaganda."

The BBC will return to Oberhausen in six months to find out what happens next.