Will Venice be loved to death?

- Published

Venice recently witnessed protests against landlords in the city letting their apartments to tourists instead of Venetians. But what can be done to preserve one of the world's greatest cities as a living entity?

The window of a chemist's shop in central Venice features a digital counter showing the number of people living in the city's historic core.

At the moment it should read 55,120 (that's up a bit, actually). But the point is that this is a countdown, raising the alarm that hundreds of people leave each year. In the past the population used to drop suddenly because of the plague. Now Venetians complain about another plague, tourism.

The French novelist Victor Hugo said there are two things about a historic building: its use and its beauty. Its use is a matter for the owner, but the beauty belongs to everyone.

Some Venetians make big money out of tourism: they always have done. Other businesses leave and their places are taken by more hotels, vast cruise ships visit and homes become holiday lets.

Venice is visited by 20 million tourists each year

Venetians are leaving the place they call La Serenissima - "the most serene" - a city currently visited by 20 million tourists a year. The big question is: will Venice end up killed by its own beauty, loved to death?

"For working people, it's becoming unworkable," says Sarah Quill, who has photographed the city for four decades and whose archive illustrates the stark contrast between a city once populated by Venetians and now in the grip of an increasing tourist overload.

"It's impossible to avoid the centre if you have appointments and those peaceful early mornings are now a distant memory."

Part of Venice's problem is what it represents. It is a city of comfort and consolation in an era of furious urbanisation. If you live in a Chinese megalopolis of 30 million souls which was not there not long ago, Venice will seem an ideal polar opposite.

Unable to expand over the water that surrounds it - it is built on islands in a lagoon - it is the gold standard for the city of human scale, the world's sentimental ideal city.

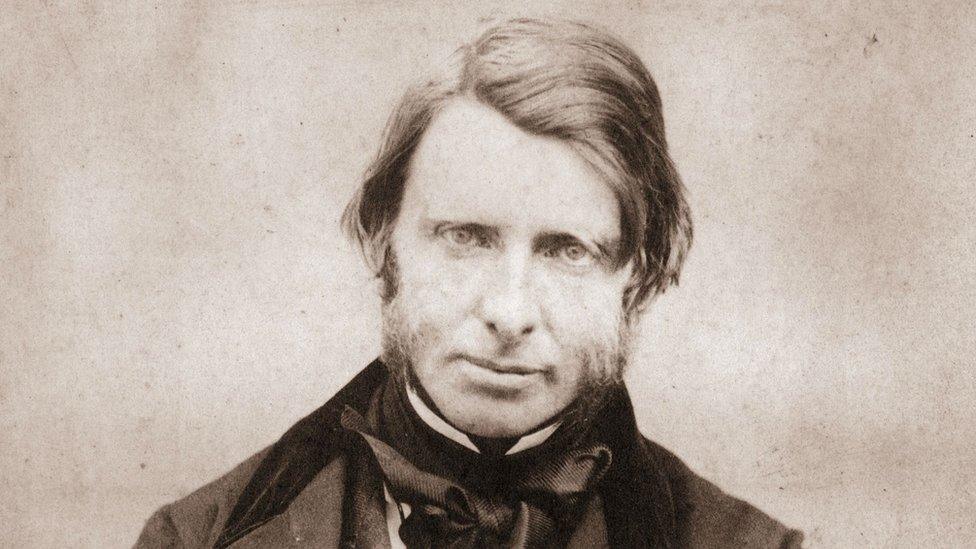

The writer John Ruskin first mooted a surcharge to visit the city

So what can be done to save sentimentality from economics? Venetians complain about the Chinese buying bars and houses today. Before them it was the Russians, the Americans and, 200 years ago, probably the Austrians.

The greatest writer on Venice, John Ruskin, suggested a tongue-in-cheek extra charge to visit, as do some of today's Venetians. A surcharge would raise money but surely not reduce numbers, which is what is needed.

Today's protesters say if you put a gate on it you make it a theme park, not a living city. Why not call it a reservation, for preservation?

As its a cultural Mecca, why not do what Mecca does and limit the annual number of pilgrims? Visiting Venice is, maybe, not a human right.

In his novel England England, Julian Barnes imagined a tourist's version of England built on the Isle of Wight - all the best bits recreated in one convenient place.

England England is such a success it becomes an independent state and joins the EU while actual England goes into decline. Could we imagine a Venice 2.0/Venice Venice?

The Venetian Hotel on the Las Vegas Strip in Nevada is just one replica of the famous city

Sadly the Japanese version, an Italian shopping experience called Italmura, with canals and gondolas, went bust.

But there are commercially successful replicas in Dubai, Qatar, Istanbul and, of course, Las Vegas, where the Venetian Hotel has opened a replica of its replica in Macau - even though China already has a copy of its own, Venice Water Town, a suburb of Hangzhou.

And even Venice itself is not entirely genuine. Those horses on St Mark's basilica are copies: do you mind? The medieval bell tower opposite fell down in 1902 and was rebuilt brick-for-brick. Can you tell the difference?

Could we not embrace the fake to help the real? Venice is like the panda: charismatic, unsuited to life today but too symbolic to be allowed to disappear. If our beloved wild animals end up existing only in zoos or reservations why not cherished cities?

Let's have a new Venice island experience - all the highlights recreated from scratch in one place and better organised for better pictures. Reliable tides, none of the smells and with better food and plumbing.

And you and I, obviously we can go to the old Venice and play spot the difference.

The World This Week is on BBC World Service Radio and available as a podcast.

- Published12 November 2016

- Published26 September 2016