Why was IMF chief Lagarde put on trial?

- Published

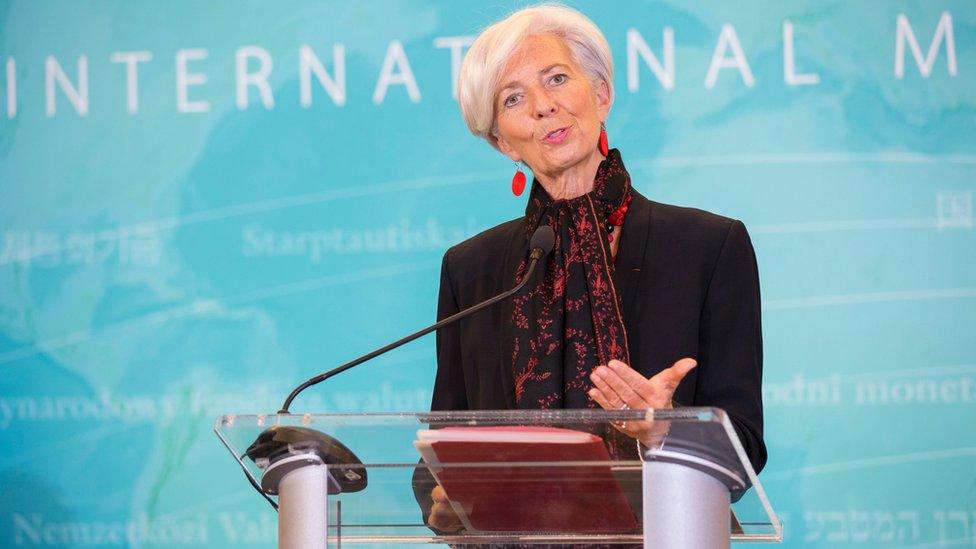

Christine Lagarde has been IMF director since 2011

The head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Christine Lagarde, has been found guilty of negligence after a trial in France over compensation awarded in 2008 to Bernard Tapie, a well-connected businessman, when she was finance minister.

Although she has avoided a sentence, Ms Lagarde had denied wrongdoing and the verdict came as a shock. The IMF had backed her through the judicial saga, and prosecutors said while she had made a bad decision, they did not see it as an offence.

Why was she taken to court?

It is a story that all began with a big business deal in the early 1990s that years later led to accusations of cronyism levelled against several leading French figures, including Christine Lagarde.

In 1993, Bernard Tapie had to sell his business interests to become a minister in the then Socialist government.

When sports goods manufacturer Adidas was sold on his behalf, Credit Lyonnais (CL) bank found buyers for the equivalent of €320m in 1993. The state-owned bank said this was a good price, but investors immediately sold Adidas on for €560m, and Mr Tapie cried foul.

Bernard Tapie is a flamboyant businessman who has served time in prison

Mr Tapie argued that the bank had deliberately undervalued the company, and pointed out that one of the firms that had flipped Adidas for a huge profit was a subsidiary of CL. He sued the bank for fraud in a court battle that went on for many years.

Why was Christine Lagarde caught up in it?

As finance minister from 2007-11 under centre-right President Nicolas Sarkozy, she played a key role in the initial settlement. In 2007, she decided to refer the long-running case to final arbitration.

This decision was controversial as Mr Tapie had thrown his support behind Mr Sarkozy in the election.

In 2008 the three-member panel awarded Mr Tapie not just compensation, but also interest and other costs - for a total of €404m ($429m; £340m). That included €45m for "moral damage".

Christine Lagarde was previously finance minister in Nicolas Sarkozy's administration

Ms Lagarde decided not to challenge the ruling, prompting an outcry.

Critics argued that by going to binding arbitration rather than continuing fighting Mr Tapie through the courts, she was repaying favours.

Profile: IMF chief Christine Lagarde

Many accused Ms Lagarde of cronyism, and in 2011 a group of Socialist MPs launched a corruption case against her.

The whole compensation deal was eventually thrown out and Mr Tapie was ordered to repay the €404m.

Paris prosecutors later targeted parties to the 2008 decision - including Mr Tapie, arbitrators and other officials - on suspicion of fraud and misuse of public funds.

Investigations are still ongoing but Ms Lagarde was tried by France's highest court and cleared of the most serious charges in 2014.

So why was she put on trial again?

The court in 2014 said Christine Lagarde's decision to settle the case through arbitration had demonstrated a "grave negligence".

Prosecutors argued that she had not committed an offence, but simply made a poor decision.

However, the Court of Justice of the Republic (CJR) rejected their recommendation. Ms Lagarde was accused of negligence and faced hostile questioning during the five-day trial.

What happened in court?

One of the key moments came when ex-treasury official Bruno Bezard told the court that the government had been warned on several occasions not to go to arbitration, which had "colossal risks".

But it was not clear that the warnings had reached Ms Lagarde. Her then chief of staff, Stephane Ricard, decided not to give evidence in the trial.

However, when the €404m payout was recommended by the panel, Mr Bezard said the decision not to appeal was "scandalous", he said.

Although Ms Lagarde said she had taken her time before deciding not to contest the payout, Mr Bezard spoke of his shock at the speed at which she took the decision.

Chief prosecutor Jean-Claude Marin spoke of " very weak accusations" that were not sustained by the evidence. On the final day of the hearing, Christine Lagarde appeared to be close to tears as she defended her record and described a five-year ordeal.

The risk of fraud had never occurred to her, she said. "I acted in good faith and good conscience with the sole aim of defending the general interest," she insisted.

Why did she avoid a sentence?

The CJR ruled that Ms Lagarde had been personally implicated in the decision not to challenge the panel's decision.

And yet it decided not to hand down a criminal penalty because it said her national and international reputation had to be taken into account.

It is not yet clear how far her reputation will be tarnished. Although there can be no appeal, her lawyer has said they will try to contest the ruling.

Why is the court unusual?

The CJR was set up in 1993 to handle crimes allegedly committed by cabinet ministers.

As it is composed of 12 politicians and three magistrates, many see it as a way of using the court system to wage political battles.

Outgoing French President Francois Hollande has vowed to scrap the CJR, arguing that government ministers should be treated like ordinary citizens.

But the court remains in place, and has just held one of the highest-profile cases in its short history.

- Published19 December 2016