Are we heading towards a 'post human rights world'?

- Published

With an increasing number of states seemingly reluctant to honour human rights treaties, is there a future for this type of international agreement?

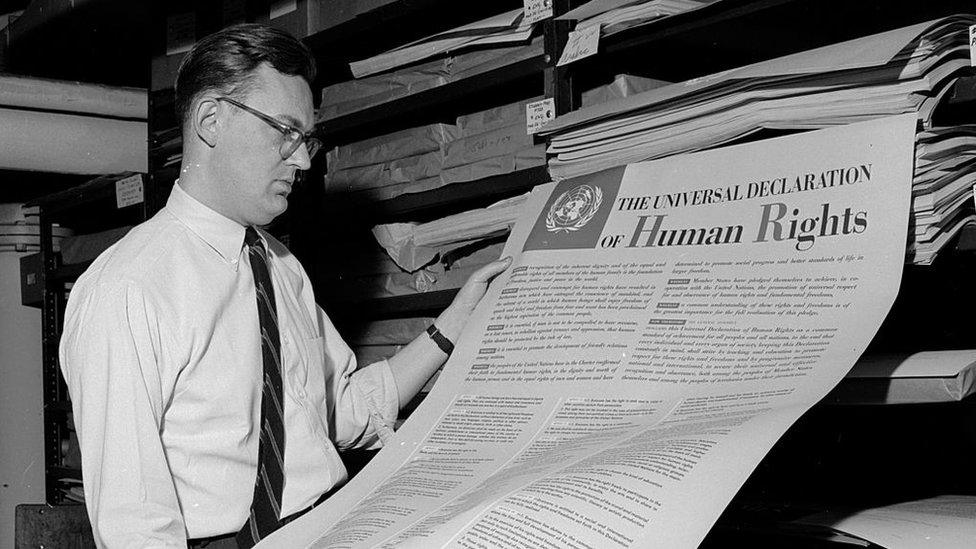

"We stand today at the threshold of a great event both in the life of the UN, and in the life of mankind."

With these words, Eleanor Roosevelt presented the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to the United Nations. It was 1948 and UN member states, determined to prevent a repeat of the horrors of World War Two, were filled with idealism and aspiration.

The universal declaration promised (among other things) the right to life, the right not to be tortured, and the right to seek asylum from persecution. The declaration was followed just one year later by the adoption of the Geneva Conventions, designed to protect civilians in war, and to guarantee the right of medical staff in war zones to work freely.

In the decades since 1948 many of the principles have been enshrined in international law, with the 1951 convention on refugees, and the absolute prohibition on torture. Mrs Roosevelt's prophecy that the declaration would become "the international magna carta of all men everywhere" appeared to have been fulfilled.

But fast forward almost 70 years, and the ideals of the 1940s are starting to look a little threadbare. Faced with hundreds of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers at their borders, many European nations appear reluctant to honour their obligations to offer asylum. Instead, their efforts, from Hungary's fence to the UK's debate over accepting a few dozen juvenile Afghan asylum seekers, seem focused on keeping people out.

Meanwhile across the Atlantic, president-elect Donald Trump, asked during the election campaign whether he would sanction the controversial interrogation technique known as "waterboarding", answered 'I'd do much worse… Don't tell me it doesn't work, torture works… believe me, it works."

"Torture works," US president-elect Donald Trump said during his election campaign

And in Syria, or Yemen, civilians are being bombed and starved, and the doctors and hospitals trying to treat them are being attacked.

Little wonder then, that in Geneva, home to the UN Human Rights Office, the UN Refugee Agency, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the guardian of the Geneva Conventions, there is talk of a "post human rights" world.

"There's no denying that we face enormous challenges: the roll-back that we see on respect for rights in western Europe, and potentially in the US as well," says Peggy Hicks, a director at the UN Human Rights Office.

Just around the corner, at the ICRC, there is proof that those challenges are real. A survey carried out this summer by the Red Cross shows a growing tolerance of torture. Thirty-six per cent of those responding believed it was acceptable to torture captured enemy fighters in order to gain information.

What's more, less than half of respondents from the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, among them the US and the UK, thought it was wrong to attack densely populated areas, knowing that civilians would be killed. More than a quarter thought that depriving civilians of food, water and medicine was an inevitable part of war.

For ICRC President Peter Maurer these are very worrying figures. "Even in war, everyone deserves to be treated humanely," he explains. "Using torture only triggers a race to the bottom. It has a devastating impact on the victims, and it brutalises entire societies for generations."

ICRC president Peter Maurer says using torture "triggers a race to the bottom" on human rights

But how many people are listening, outside the Geneva beltway? Peggy Hicks attempts an explanation as to why attitudes to human rights may be changing.

"When confronted with the evil we see in the world today, it doesn't surprise me that those who might not have thought very deeply about this [torture] might have a visceral idea that this might be a good idea."

But across Europe and the United States, traditional opinion leaders, from politicians to UN officials, have been accused of being out of touch and elitist. Suggesting that some people just haven't thought deeply enough about torture to understand that it is wrong, could be part of the problem.

"I do think the human rights community, myself included, have had a problem with not finding language that connects with people in real dialogue," admits Ms Hicks. "We need to do that better, I fully acknowledge that."

What no one in Geneva seems to want to contemplate, however, is that the principles adopted in the 1940s might just not be relevant anymore. They are good, so Geneva thinking goes, just not respected enough.

"We aren't looking for an imaginary fairytale land," insists Tammam Aloudat, a doctor with the medical charity Medecins sans Frontieres.

"We are looking for the sustaining of basic guarantees of protection and assistance for people affected by conflict."

The medical charity Medecins sans Frontieres seeks to ensure that the rules of war are upheld

Dr Aloudat is concerned that changing attitudes, in particular towards medical staff working in war zones, will undermine those basic guarantees. He was recently asked why MSF staff do not distinguish between wounded who are civilians, and those who might be fighters, who, if treated, would simply return to the battlefield.

"This is absurd, anyone without a gun deserves to be treated… We have no moral authority to judge their intentions in the future."

Extending the analogy, he suggested that doctors or aid workers could end up being asked not to treat, or feed, children, in case they grew up to be fighters.

"It's an illegal, unethical and immoral view of the world," he says.

"Accepting torture, or deprivation, or siege, or war crimes as inevitable, or ok if they get things done faster is horrifying, and I wouldn't want to be in a world where that's the norm."

And Peggy Hicks warns against hasty criticism of current human rights law, in the absence of any genuine alternatives.

"When we look at the alternatives there really aren't any," she said.

"Whatever flaws there may be in our current framework, if you don't have something to replace it with, you better be awfully careful about trying to tear it down."