Berlin faces tough choice between freedom and security

- Published

The market attack has widened the political gulf in Germany

For many Berliners, the one word most associated with their city is "freedom".

The freedom to be who you want, live how you want, and love who you want.

So when Berlin Mayor Michael Mueller called this tragedy an "attack on our freedom", he meant an attack on the essential character of this city.

Which is why so many people here say they refuse to be cowed by terror - even though there is certainly reason to be nervous.

The attacker is still on the run, is potentially dangerous, and possibly armed. The prime suspect is Anis Amri, a 24-year-old Tunisian citizen, who came to Germany in July 2015 as an asylum seeker.

Within a year, his application for asylum had been rejected - but he was still granted temporary permission to stay.

If he turns out to be responsible for the attack, Germany's authorities will be asked: why wasn't he deported?

There are in fact many legal reasons why it can be impossible to deport someone whose application for asylum has been rejected - such as having no documents or if the country of origin refuses to take him back.

In Amri's case, German officials say Tunisia would not accept that he was one of its citizens.

About 160,000 people in Germany have similar status.

Anti-migrant campaigners want them deported. Pro-refugee groups say they live in limbo - often unable to work, and with only temporary residence rights, they have little prospect of integrating.

Signs reading 'Merkel must go" are waved by right-wing groups outside the German Chancellor's building

Either way, it was already a controversial issue. Now it's likely to turn into a major political headache for the government.

The other big question is security.

Berliners' love of freedom can also mean freedom from state surveillance. That is why CCTV cameras, allowed in other parts of Germany, are banned in public spaces in Berlin.

Because of the attacks, the government is now pushing through new legislation to allow more security cameras.

More police officers will also be employed and there are controversial proposals to boost the role of the army domestically.

But it is Chancellor Angela Merkel who is most under the most pressure. She is associated with a pro-refugee stance more than any other European politician.

It is a mistake to say she has an open-door policy to migration. She negotiated the EU deal on returning migrants from Greece to Turkey, much criticised by refugee groups, that has drastically reduced migrant numbers.

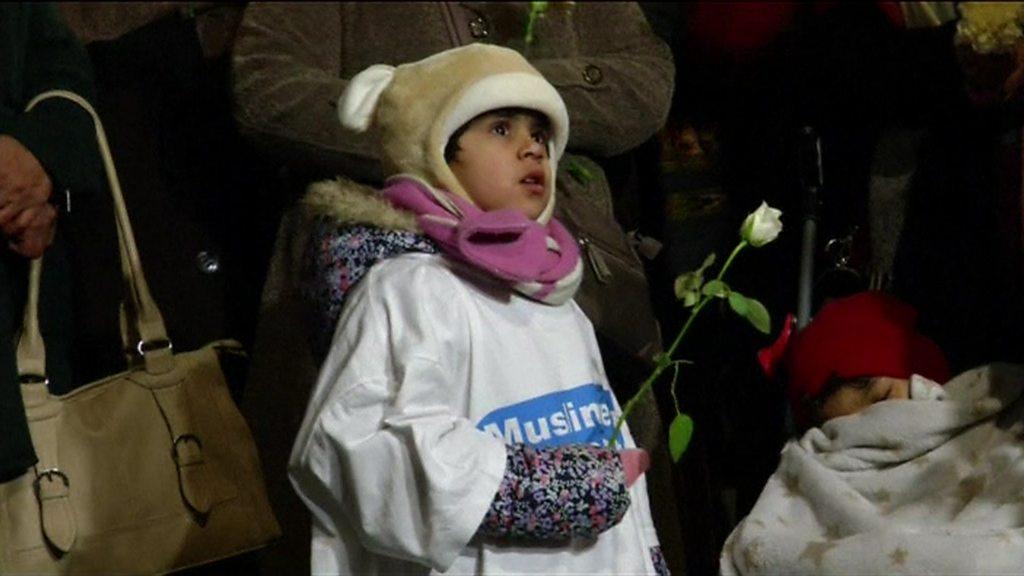

A counter-protest was held opposing the far-right on Wednesday, near the scene of the attack

And to keep migrants out, Mrs Merkel has suspended the free border regime between Austria and Germany. Her government is also pushing through new laws to curb benefits for EU migrants.

In reality, she has struck a relatively centrist position, standing by her conviction that Germany has a humanitarian duty to help legitimate refugees - in line with mainstream opinion in Germany.

But that means she has become a hate figure for the insurgent populist anti-migrant party Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Vice chair of German right wing party tells The World at One that Chancellor Merkel is to blame for attack

Mrs Merkel and the AfD have become sworn political enemies. She accuses them of whipping up hatred and dividing society. They stage rallies with posters portraying her with blood on her hands. Those are the two poles dividing German society.

The refugee question is an issue that polarises the country in the same way that Brexit does in Britain or gun control does in the US.

So far, the attack on the Christmas market seems to be making that political gulf wider, rather than suddenly creating a shift in public opinion.

Berlin has been through a lot over the past century, including destruction, division and dictatorships. So Berliners are a tough breed. And they are certainly not going to let themselves be intimidated.

- Published21 December 2016

- Published23 December 2016

- Published22 December 2016

- Published20 December 2016

- Published24 December 2016

- Published20 December 2016

- Published20 December 2016

- Published20 December 2016

- Published19 December 2016

- Published20 December 2016