Will Catalonia try to secede from Spain this year?

- Published

Catalonia: Sun, sand, sea... and secession?

If the stand-off between the Spanish state and the north-eastern region of Catalonia has been intense for the past five years, 2017 looks set to be explosive.

Catalan leader Carles Puigdemont set the tone in a New Year message, saying a planned referendum would go ahead by September. That would defy the Spanish government's warning that any vote organised by Catalonia's regional authorities would be illegal.

"If 50% plus one vote 'yes', we will declare independence without hesitation," he said.

Tensions between supporters of independence and Spanish authorities are likely to rise when three senior Catalan ex-officials, including former president Artur Mas, go on trial accused of criminal disobedience for organising a wildcat poll in November 2014.

Spain's conservative prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, says he is willing to negotiate possible alterations to the relationship between the national and Catalan administrations, but will not discuss changes to Spain's constitution.

Artur Mas has spearheaded the Catalan campaign for independence

Catalonia's quarrel with Madrid

So Madrid says there will be no referendum. Barcelona insists there will be a vote and it will be binding.

"If we have 50% turnout and a majority in favour of independence, this will be legitimate. Then Madrid will have to ask itself if it is going to impose its laws by force, if the Catalan people choose their future peacefully and democratically," says Joan Maria Pique, the Catalan government's director of international communications.

The image of tanks rolling north across the Ebro river belongs to Spain's tragic civil war of the 1930s. But how would Madrid react if Catalonia made a unilateral declaration of independence?

When Spain's defence minister until last November, Pedro Morenes, was asked what the army would do in such a scenario, he avoided giving a direct answer: "If everyone does what they are legally bound to do, that situation will not be necessary."

Could Catalonia simply secede?

Like other regions in Spain, Catalonia already has the power to run its educational and healthcare systems, as well as limited freedoms in the area of taxation. But Spanish constitutional experts offer little encouragement to supporters of independence for Catalonia.

"If the Catalan government does not negotiate the calling of a referendum with the state, it is not legally possible, because this power is held by the central state," explains Javier Garcia Roca, professor of constitutional law at Madrid's Complutense University.

Spain's constitutional court agrees. It outlawed the unofficial vote held in November 2014, and that ruling led to former Catalan President Mas and two of his ministers facing trial this year. If found guilty, Mr Mas could be barred from public office for a decade.

Rebel town halls

Surveys suggest a referendum vote on secession would be close

Many Catalan towns and villages have gone ahead and declared independence in a symbolic but defiant fashion.

A picturesque Costa Brava fishing village, El Port de la Selva, declared itself "morally excluded" from Spain's constitutional order in July 2010. Earlier Spain's top court had ruled that large chunks of the Catalan autonomy statute, approved by both the Spanish and Catalan parliaments, were unconstitutional.

The number of rebel municipalities has gone on growing.

One estimate from a pro-sovereignty association suggests 787 of the region's 947 town and city halls have declared support for "decoupling from the Spanish state".

Several local politicians and hundreds of councils are being investigated for offences deriving from symbolic disobedience of Spanish laws.

The constitutional court has also quashed several attempts by the Catalan parliament to vote into existence "instruments of state" for a future independent country, including a tax agency and a social security department that would form the basis of a new welfare system.

It has also annulled laws against fracking, gender inequality and banks which keep empty homes on their books. In 2010 the court sparked outrage by removing the preferential status of the Catalan language and quashing another dozen articles.

Catalan spokesman Joan Maria Pique accuses the Spanish government of "exercising juridical violence by violating the independence of the courts".

"The constitution lays down the principle of unity of the state and nation, which are described as 'indivisible'," argues Prof Garcia Roca. "It is a rigid document and the possibilities for imagination and constitutional engineering are therefore not the same for Catalonia as for Scotland."

Solar panels at a Barcelona cemetery: It is one of the most developed regions in Spain

Game of political chicken

And yet much of Catalonia believes that it has already triggered what pro-independence circles describe as "decoupling" from the Spanish state, backed by a majority of the Catalan parliament and the region's local councils.

A recent poll published by Barcelona-based newspaper El Periodico, not seen as backing independence, suggested that 85% of Catalans wanted a referendum, which all surveys predict would be extremely tight.

So while the Madrid government insists any vote will have no validity, the game of political chicken goes on.

Court orders have been served on councillors in Catalonia who refuse to acknowledge Spanish national holidays, remove flags or bow to other constitutional requirements, or who burn images of Spain's King Felipe.

Meanwhile, the tension continues to rise. Something will have to give.

Collision course

June 2010: Spain's constitutional court quashes parts of Catalonia's autonomy statute

11 September 2012: Barcelona's police estimate at 1.5 million the number of people attending the Diada march for independence

20 September 2012: Prime Minister Rajoy rebuffs Catalonia bid to cease being net contributor to the Spanish state

9 November 2014: Catalan authorities hold consultation on secession - more than 80% vote in favour, but turnout is only 40%

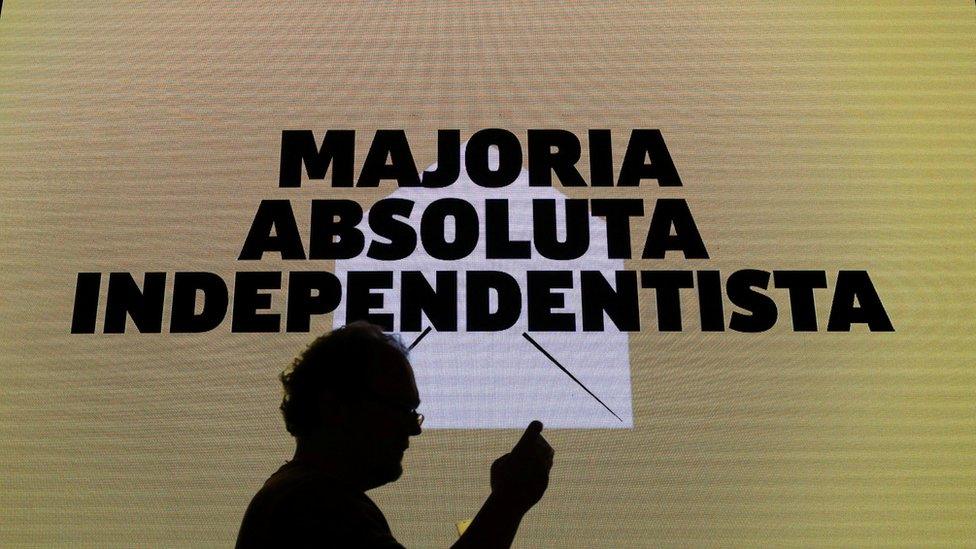

27 September 2015: In regional elections presented as independence plebiscite, pro-sovereignty forces win majority of seats with 48% of popular vote

- Published18 October 2019

- Published21 August 2023

- Published11 September 2016