Cyprus peace talks: Can Cypriots heal their divided island?

- Published

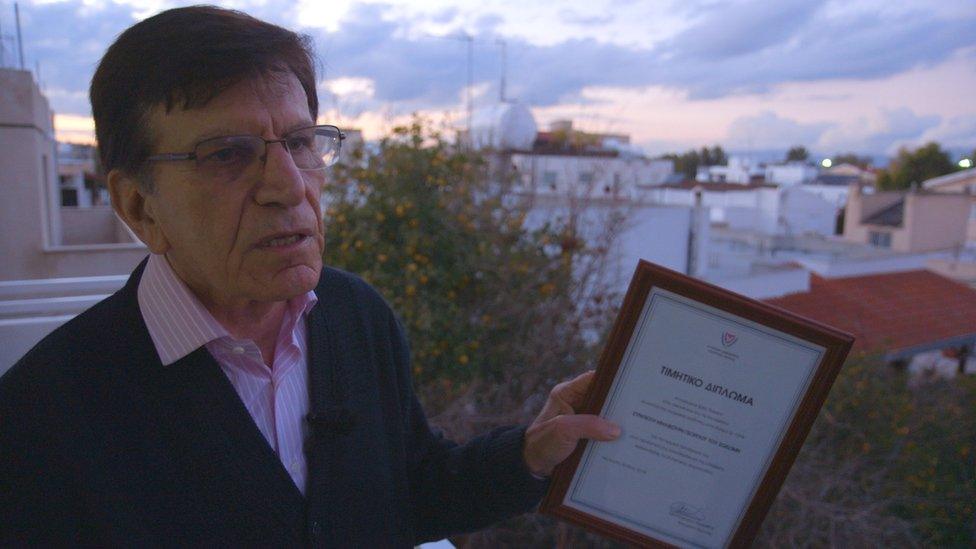

Abdullah Cangil, who was forced to emigrate from southern Cyprus to the north, says he is happy to hand back his house

Abdullah Cangil is a 66-year-old Turkish Cypriot, living in Morphou - a border town on the divided island of Cyprus.

His three-bedroom house is surrounded by orange and lemon trees. The chirping of birds can be heard all around the garden. He says he planted the trees here himself, as he reaches to one of them to grab a few mandarins to offer me.

Mr Cangil moved to this house in 1974, after Turkey invaded Cyprus in response to a coup aiming to unite the island with Greece. This was followed by a population exchange.

Around that time, 165,000 Greek Cypriots were displaced, while about 40,000 Turkish Cypriots were uprooted in total in inter-communal violence in the 1960s and the population transfer in 1975.

Abdullah Cangil was one of those who left his house behind. After 24 years in Paphos, a southern Cyprus town, he was forced to emigrate to the north.

"A Greek Cypriot family lives in our house in Paphos and we live in a Greek Cypriot family's house here," he says. "We all see each other, we became very good friends in time."

But what if he needs to hand his current home to its previous owners?

"I never felt attached to this house. I always knew one day I would need to leave it behind. It is its real owners' right to live here," he replies.

"The future of my grandsons, that is more important than a house. Peace is more important. I don't want my children to live the wars, the troubles that we have gone through. It is much more important to have peace than to move from one house to another."

Greek Cypriots from the town of Morphou stage a protest outside the presidential palace in Nicosia

Morphou, or Guzelyurt as it is called by Turkish Cypriots, is one of the thorny issues at the peace talks under way in the Swiss town of Geneva.

Greek Cypriot leader Nicos Anastasiades has warned that there can be no deal without a full return of the town, while some on the Turkish Cypriot side say that is out of the question.

Although the talks in Geneva are labelled as the most intense effort in more than a decade to reunite the divided island of Cyprus, there is slow progress and the hopes for a breakthrough are already dimming.

But the two sides - for the very first time in the long history of Cyprus negotiations - have presented their respective maps of the future internal boundaries of a federated Cyprus.

The details of the maps are yet unclear, but it is expected that the territory under Turkish Cypriot control could shrink from its current 37% to just under 30%.

The fate of Morphou remains to be seen too, as emotions still run high on both sides of the island over the matters of territorial exchange and compensation for lost property.

But that is not the only hurdle in these negotiations. The foreign ministers of Greece, Turkey and Britain, guarantor powers of Cyprus's independence, are scheduled in Geneva on Thursday to discuss the security concerns within a possible deal - another challenging topic.

Turkey has about 35,000 troops in northern Cyprus. Greece and the Greek Cypriot government strongly contest their presence and demand all of them are pulled out - hardly a demand Turkey would be happy to meet.

In general, Turkish Cypriots, fearful of past experiences of being targeted by Greek Cypriot nationalists, also want Turkish guarantees to continue.

The wounds of the past are hard to heal in both communities and there is a mutual distrust of one another.

Bird droppings cover seats inside the old Nicosia airport, now located in the UN-controlled buffer zone that separates the north and south of Cyprus

One place that stands as a monument to that distrust and how to overcome it lies within the UN-controlled buffer zone that divides Cyprus along ethnic lies.

The Committee on Missing Persons (CMP) located here is a bi-communal body established in 1981 with the participation of the UN.

Its aim is to recover, identify and return the remains of the people who went missing during the atrocities mainly taking place in 1963-64 and 1974.

According to a list agreed by the leaders of Turkish and Greek Cypriot communities, 2,001 people have been identified as missing persons - though it is believed that the number could be much higher.

Around 500 of them are Turkish Cypriots and the rest Greek Cypriots - 1:3 being the exact proportion of the respective communities to each other.

The first missing person was exhumed in 2007 and since then about 750 people have been identified, their remains returned to their families.

Over a thousand sites have been dug until now, and excavations are still being carried out.

The remains of 25 people have been uncovered in the past few months alone

The Committee on Missing Persons aims to return the bones of the missing to their families

Rania Michail is in the team of anthropologists digging at a previously Orthodox cemetery in Morphou.

Since they started searching this place six months ago, they have managed to excavate 25 missing people's remains, she tells me - 12 soldiers, 12 old women and 1 person's general body parts.

"Sometimes it gets difficult emotionally. Especially if we find the remains of a child," Rania says.

"The first time that I saw remains five years ago, it was the most shocking moment of my life. I was really upset. That night I could not sleep. But then I got used to it. I have excavated over 100 bodies - women, soldiers, kids - both in the north and in the south of the island."

At the CMP's headquarters in the UN-controlled buffer zone, the anthropologists study the remains carefully, trying to reconstruct them and to identify those killed.

Skulls and bones are laid on top of tables along with whatever was found lying with the remains - a pair of socks, a piece of underwear, a lighter, or a picture of a loved one.

"What we do here is very important for achieving peace in Cyprus," says Uyum Vehit, an anthropologist.

"Almost every single family has missing persons. If they don't receive the remains, and if they don't have proper graves, they can't have a closure."

Kyriacos Solomi lost his younger brother, George, in the violence

At his home on the Greek side of the "Green Line" line in Nicosia, Kyriacos Solomi, 68, still waits for the remains of his younger brother, George, who was killed on the front line 42 years ago.

"He was a very peaceful man. He liked mixing with people, enjoying life, peaceful activities. He was a nice, healthy, good-looking young man, 24 years old," he says while trying to hold back the tears when he looks at his brother's picture in his hand.

"This is a very deep wound. It may close one day but a big scar will stay there forever."

Despite having lost his brother, Mr Solomi still believes in peace - but he doubts whether it can ever be reached in Cyprus.

"There is no other way to survive on this island. We fight for peace. I know the clock cannot go back, the lives will not come back.

"But I don't think peace will come here. Maybe in the next generations, if they can change the textbooks that spread hate instead of love.

"Listen to the TV, listen to the church: they are spreading hate. I don't think we can live peacefully with hatred on this island," he says.

For more than 40 years Cyprus has been a divided island.

- Published12 January 2017

- Published11 January 2017

- Published9 January 2017

- Published11 January 2017

- Published8 January 2017

- Published10 January 2017