Child migrant’s body sparks soul searching in Spain

- Published

Some migrants are rescued, but the UN estimates 20,000 have died trying to cross to Spain in the last three decades

Spanish protesters gathered in the central square of Barbate, near Cape Trafalgar, to mourn the death at sea of a young boy from Africa.

He is being described as Spain's Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian refugee whose lifeless body was photographed on the Turkish shore in 2015. The picture was seen by millions and prompted outrage at the plight of refugees.

The decomposed body removed from a beach near Barbate by police last Friday is believed to be that of a six-year-old from DR Congo called Samuel. He died along with his mother when their flimsy inflatable boat sank during an attempt to cross the Strait of Gibraltar between Morocco and Spain.

The number of migrants' bodies accounted for off the Spanish coast is officially in the hundreds. But the UN's refugee agency has calculated that more than 20,000 people have perished trying to cross to mainland Spain or on the Atlantic route to the Canary Islands since 1988.

"We don't know how many Alans, how many Samuels or how many men and women lie at the bottom of the sea without their families knowing anything," said Rafael Lara of the Human Rights Association of Andalusia (APDHA) at Tuesday night's demonstration.

Some 200 people reportedly attended, in Mr Lara's words, "to express revulsion at the deaths on our borders caused by the sectarian politics of our governments".

The boat that Samuel and his mother Veronique were on left Tangier late at night on 11 January with 11 sub-Saharan migrants on board, according to Helena Maleno, a journalist and activist whose group is in touch with migrants in northern Morocco.

The bodies of six adults - five men and one woman - found in mid-January off the southernmost tip of Spain are believed to be from that group.

Spain's secretary of state for security, Jose Antonio Nieto, described Samuel's death as "dramatic but unavoidable" and he rejected suggestions that the government had tried to keep secret the discovery of the child's body to avoid an "Alan moment".

As US President Donald Trump's stated aim of building an anti-migration wall the length of his country's border with Mexico comes under scrutiny, Spain faces criticism for what human rights campaigners describe as continual violations at the razor-wire fences it has constructed around Ceuta and Melilla, two cities on Africa's coast which belong to Spain but have land borders with Morocco.

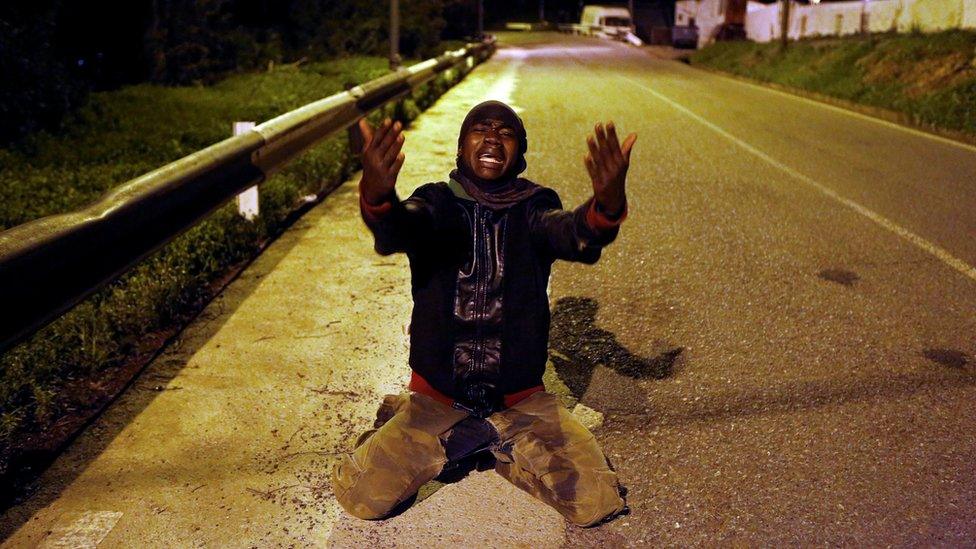

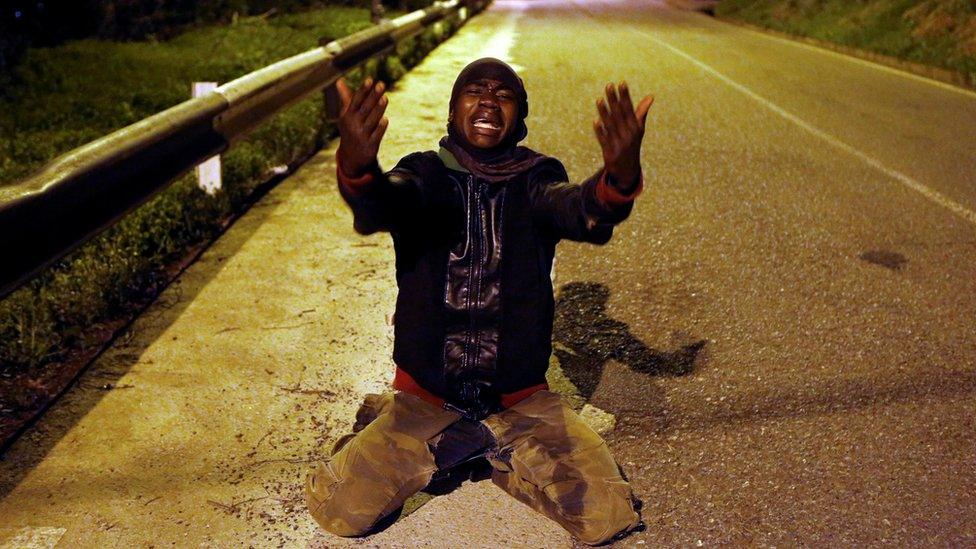

Desperate migrants regularly attempt to breach the Spanish outposts of Ceuta and Melilla on the African coast

The plight of children making terrifying attempts to cross to Spain has captured Spaniards' attention

Last month a court reopened an investigation into the death of 15 African migrants, who drowned while trying to swim their way from Morocco into Ceuta on 6 February 2014.

Although the Spanish authorities claimed that a Civil Guard border patrol team had tried to assist the migrants, the interior ministry eventually released CCTV footage from the border installations showing the officers firing rubber bullets and smoke canisters into the sea.

"They were shooting at us," one survivor said on a recently screened documentary titled Tarajal, after the name of the nearby border post. "We were bunched together in a mass and most drowned."

Spain has been criticised for sending back migrants, shown here being picked up by Moroccan soldiers in 2014

A court in Ceuta quickly shelved an investigation into the civil guards' actions, but in January an investigating judge in Cadiz decided that the case should be reopened to see if the 16 officers concerned made appropriate use of anti-riot gear.

Spain under fire

Videos of the incident also show how those migrants who managed to swim around a breakwater and reach the beach in Ceuta were instantly expelled back to the Moroccan side of the border fence, in contravention of international and national laws on refugees and the right to ask for asylum.

Spain has been criticised by a number of organisations, including the Council of Europe, for what it calls "rejections at the border".

Amnesty International said last month that more than 2,000 people had entered Ceuta and Melilla in mass assaults on the enclaves' five-metre-high (16ft) fences, but hundreds had been expelled directly to the Moroccan police on the other side without an opportunity to identify themselves.

"Spain is violating international law and preventing people fleeing wars and persecution from accessing the international protection to which they have a right," said Amnesty International Spain's director, Esteban Beltran.

- Published9 December 2016

- Published18 May 2023

- Published8 May 2015