The old-fashioned way - but can Belgrade's artisans survive?

- Published

Nenad Jovanov's shop is evocative of days gone by, but his perfumery is the only one left of 22 that once peppered Belgrade

Nenad Jovanov wields his antique atomiser with a flourish. In a puff of mist, his tiny perfume shop on one of Belgrade's oldest streets explodes with the floral aroma of "Belgrade Night".

"It is my pleasure to personally spray customers with the scent of their choice," he explains.

Belgrade Night is one of Nenad's signature creations. He formulated it for the city's Museums Night - an annual event in which dozens of the capital's galleries and historical buildings stay open late to encourage citizens to explore the cultural heritage on their doorsteps.

Nenad's shop, Sava, may not be a museum. But it is something of a time capsule.

Old-fashioned glass bottles line the wood-panelled walls. There are test tubes on the glass-topped counter. A snapshot of life in decades gone by.

More of Guy's coverage of Serbia:

Train row almost pulls Kosovo and Serbia off the rails

Kosovo's love affair with the Clintons

Can Serbia's farming heritage survive?

"I am the third generation of my family in this line of work," says Nenad. "There used to be 22 perfume shops of this kind in Belgrade; now I am the only one left."

But he is not alone when it comes to artisanal shops. A wander around Belgrade's old town soon reveals an array of craftspeople - leather-workers, milliners, upholsterers - carrying on much as they have done for decades.

Many of these shops and workshops are clustered in Savamala - a shabby riverside neighbourhood undergoing dramatic changes in the shape of the massive Belgrade Waterfront project. Many locals fear that Savamala's character - and its traditional artisans - will be swamped by high-end residential and retail developments.

Milos Kuzmanovic runs the Design Store at Belgrade culture centre Mikser House, and tries to bring the workers and their products to a wider audience. As well as stocking a permanent selection of locally-made products, he makes traditional artisans a feature of an annual festival every summer.

Family traditions

"People really like it," says Milos. "Some of them didn't know those stores still existed; we are bringing them to life and making them visible again."

Just around the corner, on Gavrilo Princip Street, the old shops are still there, at least for now.

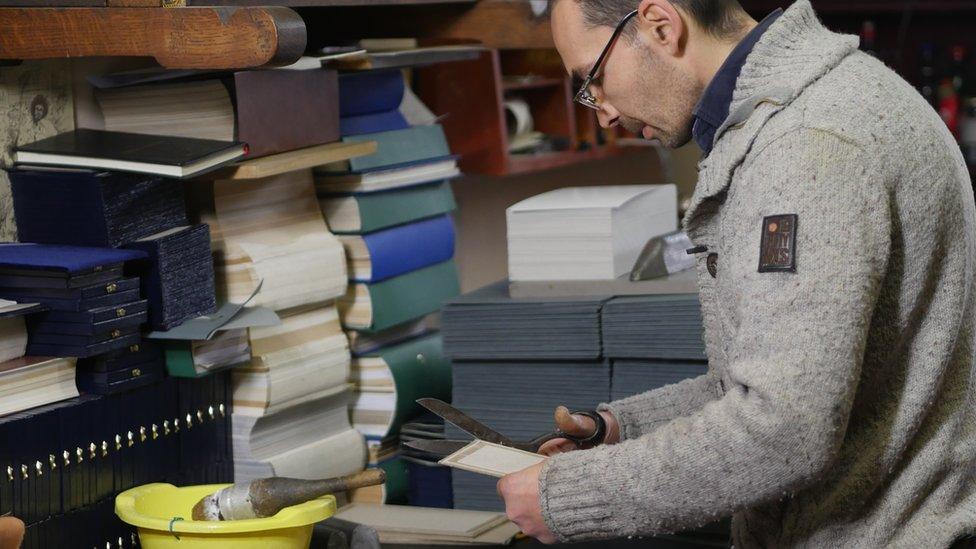

The state needs to promote traditional craftsmanship, says bookbinder Aleksandar Petkovic

But Aleksandar Petkovic is frustrated about the lack of support and understanding for the work he does.

He and his father are bookbinders, painstakingly enveloping official reports, academic texts and other documents of record in hand-cut leather, and printing the covers and spines with gold-leaf type.

"The state should be promoting this work, but it's not. A lot of my commissions come from government departments, including universities. But their budgets are being slashed."

Across the road, the Bosiljcic family bonbon emporium is the last of its kind in Belgrade.

It stocks a kaleidoscopic cornucopia of lollipops and other boiled sweets. But its speciality is hand-made delight - "Serbian, not Turkish", insists co-owner Branislav with a smile - in an array of intriguing flavours, from rose to rum-and-prune, all made on the premises behind a curtain separating the tiny retail area from the kitchen.

The Candyman? Branislav Bosiljcic creates his own bonbons in Belgrade's Old Town

On a cold winter's morning, the shop is a non-stop bustle of customers jostling to get their sweetie fix. And Branislav is optimistic about the prospects for the business he runs with his brother, following recipes handed down through generations of the family.

"We have a rising number of customers; traditional things are coming back into fashion. We must learn from our elders and don't forget - it's important for tomorrow."

In many countries, it has become cheaper to buy a new item rather than repair the old. But Belgrade's artisans still make an economic, and environmental, case for restoring the items that people already own.

That even applies to umbrellas. Tanja Zivkovic's shop on Visnjiceva Street has been making and repairing brollies for decades. It is a riot of colourful material.

Tanja Zivkovic wonders how many of the umbrellas bought today will last 40 years

Tanja lovingly caresses a Knirps brolly - "it will last for 40 years" - and raves over the stylish qualities of a Burberry. And with her daughters Jasmina and Milica also working here, she thinks that even this esoteric trade might have a future.

"My mother has been working in this shop for 50 years now. Before that, my grandfather. My daughters know how to do it - so we will see."

But even the most optimistic would probably agree that Belgrade's artisans currently find themselves in a bit of a bind.

Average incomes in Serbia hover around €400 (£340;$425) per month.

So appreciation for the artisans' work is tempered by financial reality. Young people who previously might have taken over from their parents are unlikely now to view it as a source of long-term prosperity.

That may change if Serbia's long-awaited economic recovery continues. But perhaps it would be better to make the most of Belgrade's artisans now, in case this endangered species slips away.