Switzerland votes to relax its citizenship rules

- Published

Projections show nearly 60% of voters wanted to simplify the rules

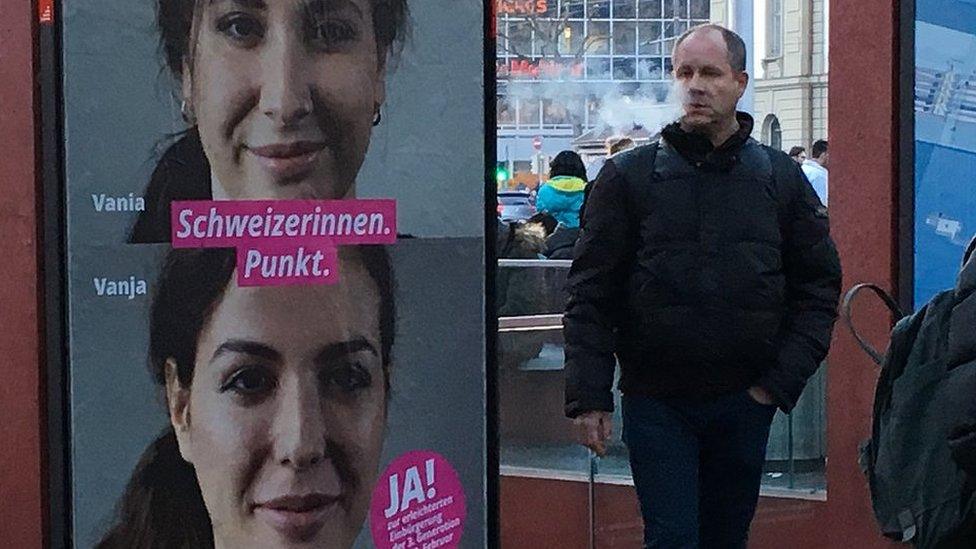

People in Switzerland have voted to relax the country's strict citizenship rules, making it easier for third-generation immigrants to become Swiss.

Being born in Switzerland does not guarantee citizenship. Non-Swiss residents must typically wait 12 years before applying.

Tests and government interviews are also required, which can be expensive.

Initial projections suggest that 59% of Swiss voters said yes to simplifying the rules.

The new proposal will exempt third-generation immigrants, who are born in Switzerland and whose parents and grandparents lived permanently in Switzerland, from interviews and tests in the naturalisation process.

Supporters of the plan to simplify the process argue that it is ridiculous to ask people who were born and have lived all their lives in Switzerland to prove that they are integrated.

Read more

The result is a defeat for the right wing Swiss People's Party, which had warned the measure was the first step to allowing all immigrants - 25% of Switzerland's population - to get citizenship, the BBC's Imogen Foulkes reports from Berne.

Some opponents had argued that the new proposal could lead to the "Islamisation" of the country.

One opposition poster featured a woman in a niqab - although this is a rarity in Switzerland.

However, the new law will affect only about 25,000 people, the majority of whom are of Italian origin, our correspondent says.

More than half of third-generation residents in Switzerland are descended from Italian immigrants, while other large groups have roots in the Balkans and Turkey.

The current vetting procedure, aimed at ensuring that new citizens are well integrated, includes interviews carried out by town councils. Questions put to interviewees can include requests to name local cheeses or mountains.

Those in favour of maintaining the current system also argue that the strict vetting rules make it superior to the more anonymous systems in neighbouring France and Germany.

Over the past 30 years, three previous attempts to relax the rules were defeated.

- Published12 February 2017

- Published11 February 2017

- Published5 December 2022