Is there a US diplomacy vacuum at the UN in Geneva?

- Published

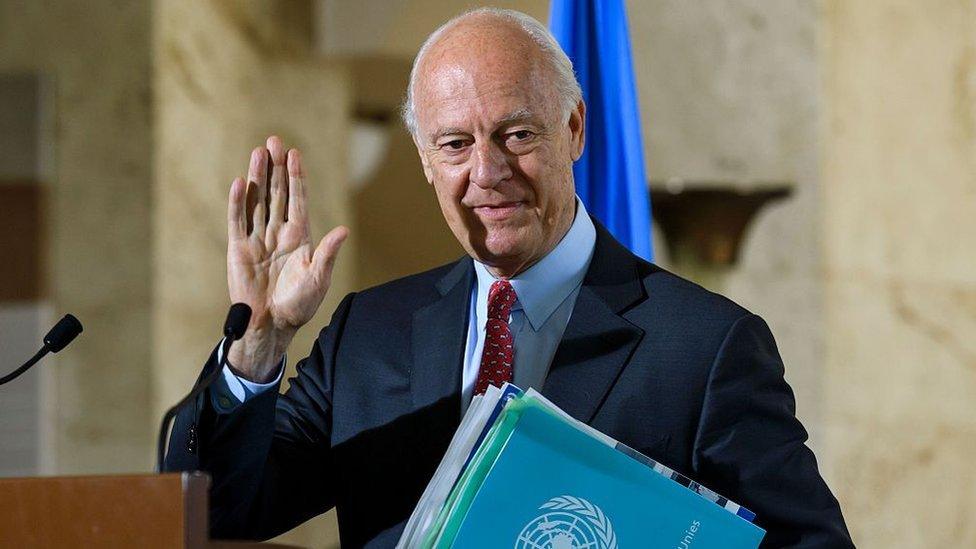

"Where is the US in all this? I can't tell you because I don't know." These were the words of the United Nations special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, days before a fresh round of peace talks began.

Only a few months ago, such a comment would have been unthinkable. Former United States secretary of state John Kerry was a regular figure in Geneva, leading US diplomacy not only on Syria, but on the Iran nuclear deal and on Ukraine.

Now, however, the US is conspicuous by its silence, the "soft power" expected of the leader of the Western world strangely absent. In Washington, there have been no State Department briefings since the new administration took over and around the world, US embassies are empty of ambassadors.

Of course it is not unusual for ambassadors, many of whom are political appointees, to change when a new administration takes office. Normal protocol demands that they submit formal resignation letters when a new president is elected.

But that does not mean the resignations are immediately accepted: in fact, ambassadors are often asked to stay on in order to ensure a smooth transition and at the very least to brief their successors.

None of this seems to have happened under President Trump: rather, dozens of diplomats were told to clear their desks and leave. In Geneva, not only are there no US ambassadors to the United Nations, there are no nominees either, meaning replacements are likely to be months away.

UN special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura

So when the UN Human Rights Council begins its four-week annual session on 27 February, what can we expect from the US? "We can't communicate a message until we know what the message is," are words heard regularly from permanent staff now operating the phones at empty US embassies across Europe.

Sources, preferring to remain anonymous, have confirmed that embassy staff have been told by Washington not to talk to the press at all. Some, not wishing to cut all ties with correspondents with whom they regularly communicate US policy, have taken to contacting journalists via Skype, from home, presumably so that their calls cannot be traced.

And so, while in recent years the United States has come to the UN Human Rights Council with bold ideas, pioneering an international campaign on LGBT rights, for example, or putting pressure on Sri Lanka to investigate alleged war crimes, this time no such action is expected.

"It is clear the United States is opting out of global governance," says Jean-Pierre Lehmann, emeritus professor at the International Institute for Management Development in Lausanne. "It's 'America First'… and populism really doesn't translate to humanitarianism."

Other observers, like Mark Halle, senior fellow at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, are not quite so pessimistic. Pointing out that the new administration is still in a transition period, Mr Halle hopes to see a "backdown when people see the consequences of the fiery declarations he (President Trump) has made".

Nevertheless, Mr Halle believes there are some areas of the UN's work where US policy is already worryingly clear. "Refugees, climate, the environment… I'm not optimistic."

The problem for the big UN agencies is not only that some of their activities may be less well-received in a Washington which has voiced scepticism about climate change and opposition to accepting refugees, it is that the UN is reliant on US funding for all its activities.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Many US diplomatic posts remain to be filled under the new administration

The US is the biggest donor to the World Food Programme (WFP), supplying more than 30% of its budget, $2bn (£1.6bn), last year alone.

The WFP has this month declared a famine in South Sudan, the first in six years, and has warned of famine in Yemen and the Horn of Africa this year as well.

To be able to support millions of people facing starvation, the WFP needs guarantees from its biggest donor that support, both moral and financial, will be sustained.

So too does the UN Refugee Agency: currently dealing with the largest number of forcibly displaced people in history, it is dependent on the US for more than a third of its funding and has long relied on America to resettle some of the world's most vulnerable refugees.

So what can the UN do to make its case in the new Washington? Mr Halle advises patience, he hopes to see "a growing up of this administration" over time. But this tactic may not help agencies dealing with immediate humanitarian crises. As one aid worker put it, "starving people don't eat retrospectively".

Mr Lehmann is less optimistic. "It is going to be very difficult for them to make the case," he says. "If I knew what the UN should do I would be picking up the Nobel Peace Prize in December."

But, even if the UN devised a bold strategy to persuade Washington of its importance, there is still the awkward question of who to pitch that strategy to.

In the absence of partners in the embassies or in the state department, some UN figures are "reaching out" to members of the US Congress for support.

Will the US remain the World Food Programme's biggest donor?

Others are still puzzling. As one senior UN official remarked, "it is not clear who we need to talk to… or where the mailbox is".

Of course, it is expected that the diplomatic vacuum in the state department and the embassies will be filled, in time. But that will present a new challenge. How should these new diplomats, political appointees of a president known to be sensitive to criticism, be handled?

Should the UN Refugee Agency, for example, question Washington's tough line on refugees from countries such as Syria, or should it stay quiet in the hopes of protecting its funding?

"Everyone is picking their battles very carefully," confessed one UN official. "We don't want to burn any bridges," admitted another.

So does the new team in Washington spell the end of multilateralism, with seismic consequences for the UN and its humanitarian operations?

"It could be a blip," suggests Mr Lehmann. "Or it could be a landmark. I tend to think this is a dramatic change."