Abortion in Ireland: The fight for choice

- Published

A vigil for Savita Halappanavar, who died in 2012 after being denied an abortion

The Irish Republic has a near-total ban on abortion, pushing thousands of women every year to travel abroad for a termination and others to break the law by taking abortion pills. On International Women's Day on Wednesday, women across the state will protest for a change in the law.

Sarah didn't know where to turn when she found out she was pregnant. It was May last year, she was 23, finishing her final year at university, and working in a cafe to save for a move from her small Irish hometown to Dublin. Waiting for her in the city were her boyfriend and a traineeship. She wasn't ready to be a mother, but her birth control had failed. Sat in her bedroom at home, she started to panic.

"I felt so alone," she said tearfully, over tea in Dublin last week. "You want to take it a step at a time but I had no idea what the next step was." Downstairs at home were her parents, who would have forced her to have the baby, she said. When she tried to raise the issue of abortion, hypothetically, they told her it was murder. "Murder, they said, and that was that."

The Irish Republic has a near-total ban on abortion, including in cases of rape, incest or fatal foetal abnormalities, and a 14-year prison sentence hangs over anyone who has one. In the early 1980s, fearing that it could be legalised via the courts, the country's Catholic hierarchy pushed for an amendment to be added to the constitution. The Eighth Amendment passed in 1983 and granted a foetus equal right to life as its mother, effectively outlawing abortion in all circumstances.

More on International Women's Day

On Wednesday, women across the state will stop work, wear black, and join demonstrations to call for the Eighth Amendment to be repealed. Campaign group Strike 4 Repeal was inspired by a similar protest in Poland last year. "We have to make a direct statement to the government," said Aoife Frances from Strike 4 Repeal. "We have to make our voices heard."

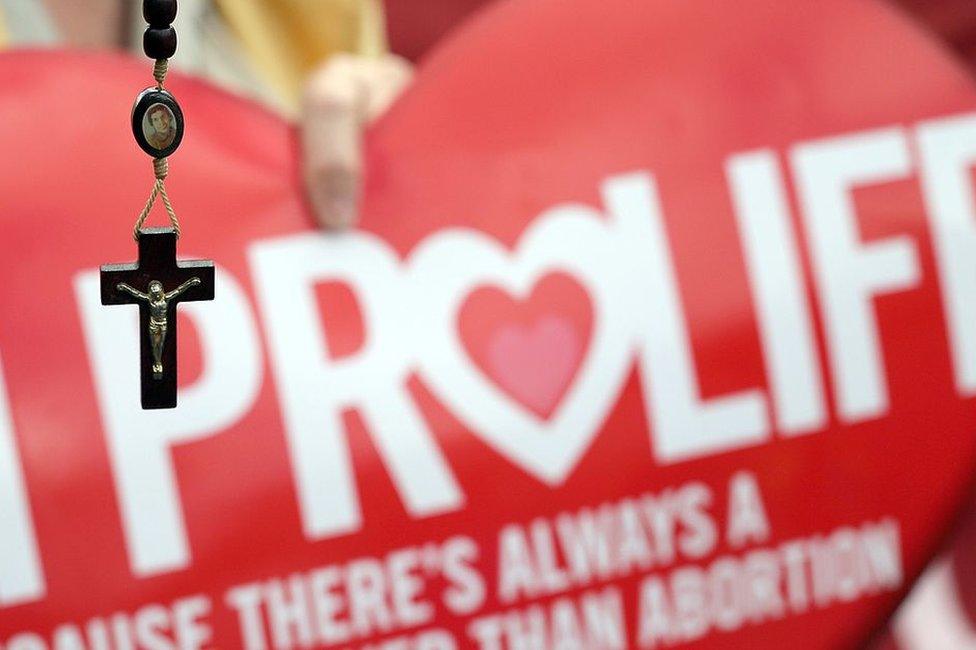

But a powerful legacy of Catholic influence holds sway over the state and many here have deeply-held religious beliefs about the right to life. Coupled with the possibility of prosecution, it has created a climate in which few women are prepared to talk openly about their experiences. Sarah asked that we didn't use her real name.

She was "terrified of telling anyone" that she planned to have an abortion, she said. In the end, she found support the way thousands of women in her situation do every year: "sheer desperation and Google". Her search turned up a number for the UK-based Abortion Support Network. "I just wanted someone, anyone, to talk to," she said, "so I drove to this random car park, dialled the number, and cried for the whole call."

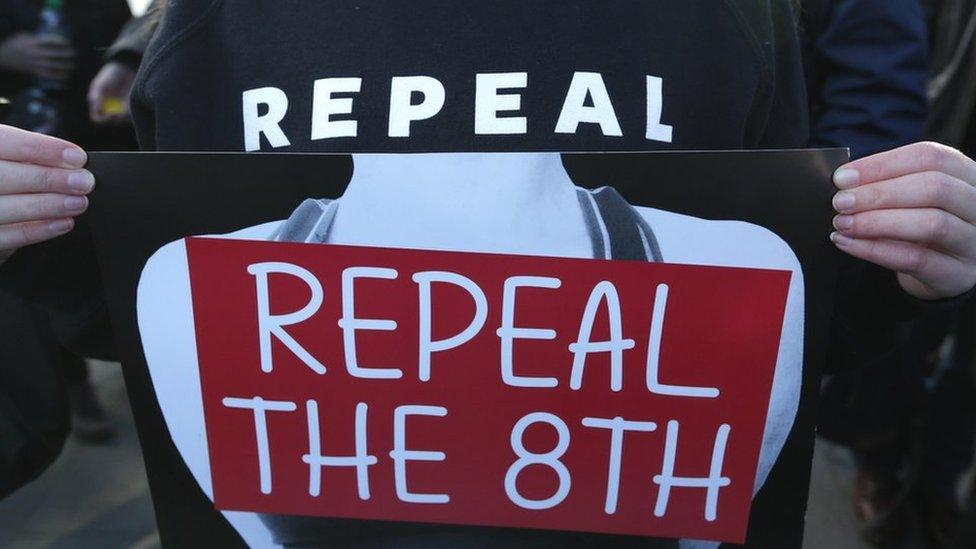

Pro-choice campaigners are calling for the repeal of the Eighth Amendment

More than 3,500 Irish women are estimated to travel abroad every year to terminate crisis pregnancies - an average of 12 per day. Mostly they go to England, often in difficult, sometimes traumatic circumstances.

Women who can't afford the costs involved - up to £2,000 for travel, accommodation, and the procedure - or who can't take time away from work, have two choices: take illegal abortion pills ordered online, or give birth. Of the estimated three women taking the pills every day, some will fear going to a doctor in the event of complications.

Sarah and her boyfriend combined their savings, borrowed some more and came up with £200. The Abortion Support Network pitched in the rest and put her in touch with a volunteer who would meet her at Liverpool airport. She took two days off work and on a cold, overcast day, boarded a budget flight to meet a stranger in a different country.

"It's traumatising to have an abortion," she said. "To not be able to do that in your own country, to not be able to return to your own home or be near your friends..." she trailed off. "I'm not ashamed I had an abortion, but to come home to a country that thought I was a criminal... I was devastated."

An Irish Times poll published last week suggests that women in Sarah's situation could wait a long time for choice. A referendum is required to change the constitution and according to the poll most of the country favours making exceptions only for rape, incest, and fatal foetal conditions.

Ruth Coppinger is an Irish member of parliament who has campaigned for years for abortion access for all women. "This is the civil rights issue of our generation," she told me. "And Ireland is headed for a rotten compromise."

Abortion in Ireland: Campaigners hit the streets

On a recent rainy afternoon in Dublin, just off O'Connell Street, pro-choice campaign group Rosa Ireland was handing out flyers and selling wristbands to raise funds.

They were preparing to take a bus around the country, to drum up support and provide consultations and abortion pills to women who want them. The pills are shipped in to Northern Ireland, where the abortion laws are nearly as strict but the customs seizures are not.

"A lot of women who contact us looking for abortion pills can't even pay their rent, so obviously they don't have a thousand euros sitting around to travel to the UK," said Rita Harrold, the group's organiser. "We rely on support and solidarity from our sisters in the North to get the pills down into the South, so we can get them into the hands of women who need them."

Women who take the abortion pills risk up to 14 years in jail

But two recent prosecutions in the North have created a climate of fear around the distribution of the pills in the South. Supplying the two drugs required — methotrexate and misoprostol — to a pregnant woman carries the same sentence as taking them: 14 years.

Another campaigner who showed us the pills themselves did not want to be filmed or have the packaging shown, as customs agents attempt to identify them by the types of envelopes and stamps used.

"The government here wants the smallest change possible, an amendment for rape," said Rita. "But why on earth would women who've been raped put themselves through a process where they are questioned and scrutinised, when they could go to the UK and be treated with dignity and respect?"

MP Ruth Coppinger is campaigning to repeal the Eighth Amendment

Barely 100 yards down the road from the Rosa volunteers, another campaign group was braving the rain to spread its message. Youth Defence is one of Ireland's largest anti-abortion groups and its stock-in-trade is shock. Boards propped up on the busy high street showed graphic images of aborted foetuses.

This is the extreme end of the debate, where abortion is compared to slavery and the Holocaust, and terminations under any circumstances are murder. Out on the high street, Youth Defence founder Ide Nic Mhathuna pointed to the graphic pictures. "These images are the reality of abortion but the mainstream media won't show it, so we are forced to," she said.

Youth Defence campaigns for abortion to remain illegal under nearly all circumstances. Allowing terminations for rape victims would be putting a "band-aid on a bullet wound", Ide said. "It's a quick fix that doesn't fix anything."

Youth Defence's tactics might be extreme but its basic message isn't - most of the mainstream anti-abortion groups have the same goal of preserving the status quo, and polls suggest that there is widespread public support for retaining relatively strict restrictions on abortion.

The Irish Pro Life Campaign takes a more traditionally compassionate tack with its PR. Its slogan is "Love Both" - the mother and child. Katy Fenton, 27, a spokeswoman for the group, said women diagnosed with fatal foetal conditions benefited from being forced to carry the pregnancy to term and seeing the child. "At the end of the day, that helps those women greatly."

Pro Life campaigners point to cases of women they say regret their abortions. Another volunteer, nursing student Peadar Hand, 21, said he had been inspired by meeting patients with regrets. "If it's driving people to feel like that it's obviously wrong," he said.

And the anti-abortion cause has significant support among members of parliament and senators. "Ireland without abortion is a much happier and humane place than an Ireland with abortion," wrote Senator Ronan Mullen in a recent op-ed for the Irish Independent.

Anti-abortion campaigners say the unborn should have rights to life

But women affected by the laws say they are being spoken for. "It's so patronising," said Claire Cullen-Delsol, whose baby daughter Alex, her third, was diagnosed in August 2015 with a fatal chromosome disorder while in the womb. Sat at her kitchen table at home in Waterford on Ireland's south coast, her heartache and anger were plain to see.

"I know myself, I don't need someone to tell me what's best for me," she said. "I don't need a bishop, I don't need a Catholic institute, I don't need an anti-abortion campaigner with some placard saying 'Love Both'. I don't need your love, I just need you to stay the hell out of my business."

Twenty weeks into Claire's pregnancy, Alex was diagnosed with Patau's syndome, a rare condition which affects foetal development and kills more than 90% of babies within a year.

Claire with her baby daughter Alex, who was diagnosed with a fatal condition in the womb

Claire and her husband Wayne desperately clung on to hope after the diagnosis, she said, fighting back tears. "I sat down and I planned out her life, and everything that she was going to do and all the love I was going to have for her," she said. But the couple's midwife called the next day. "She said I'm sorry, your baby is going to die."

Claire couldn't afford to travel to the UK for a termination so she faced the prospect of carrying Alex for four more months, waiting for her to stop kicking. "It's the loss of control," she said. "There was a way to bring me back, to help me get through it, to let me mourn and be a grieving mother, but nobody would give it to me."

Consumed by anxiety, Claire struggled to care for her two young children or leave the house. Finally, five weeks after her diagnosis, Alex's heart stopped beating and she was induced. She will be marching in Dublin on Wednesday with a sign carrying Alex's name. "Hopefully someone will be listening," she said.

A repeal mural painted on a theatre in Dublin

The Irish Government has set up up a Citizen's Assembly of 99 people, chosen at random, to hear testimony about the issue before making recommendations about the content of a possible referendum. But before any decision reaches the public it will have to go through the Dail - the Irish House of Commons - which will decide whether it's a referendum on making abortion accessible to all women or just to some.

"We get huge pressure as politicians from the moral police. I get pictures of awful, horrendous things in the post," said Kate O'Connell, a TD whose own unborn son had a severe foetal condition. He recovered and is now a healthy five-year-old who played in the background while we spoke, but she was furious to be robbed of a choice.

"The priority now is getting it right this time, so that my daughters aren't in this situation in 20 years," she said. "The legislators of this country need to realise that these women are citizens of our country and we are abandoning them at their most vulnerable moment."

Early advocates of the Eighth Amendment hoped it would permanently protect Ireland from the spectre of so-called abortion-on-demand. But the amendment didn't ensure Irish women wouldn't have abortions, it just pushed them out of sight, to clinics in London and Liverpool, and to rooms around the country where they criminalise themselves by taking pills freely prescribed elsewhere.

Sarah still hasn't told anyone that she travelled abroad for an abortion, and the thought of telling her parents still brings her to tears. "I'm too terrified I would hurt them," she said. "But if it comes to a referendum I will try and explain. Every vote will count, so I'll try."

Video production: Mohamed Madi

- Published8 March 2017

- Published7 March 2017

- Published30 January 2017

- Published26 January 2017

- Published2 March 2017