Turkish-German ties fray as Erdogan chases diaspora vote

- Published

Some 1.4 million people in Germany are eligible to vote in Turkey

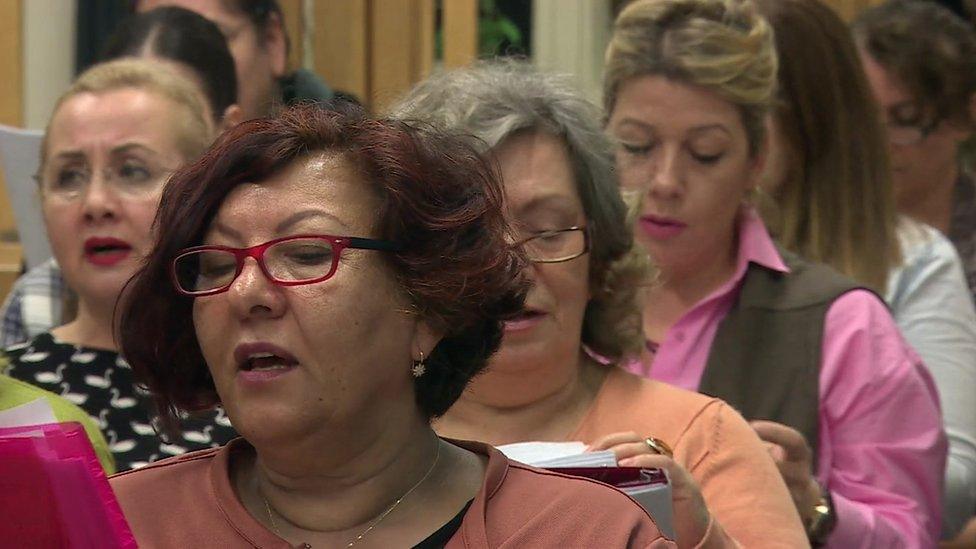

Under the strip lights of a clinical community hall in Berlin, a man's fingers slide across a zither and, eyes fixed to their sheet music, the Turkish choir begins to sing old songs of love and heartbreak.

More than three million people of Turkish origin live in Germany. It is estimated that 1.4 million of them are eligible to vote in Turkish elections. In effect, the diaspora is Turkey's fourth largest electoral district.

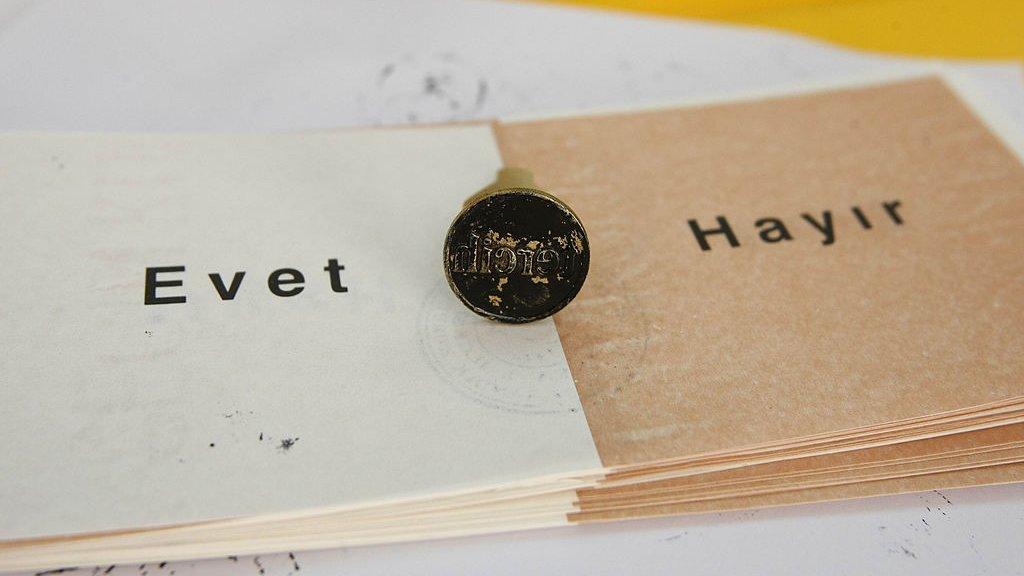

A month before a referendum on Turkey's constitution, there's a louder Turkish voice resonating in the heart of Germany.

President Recep Tayip Erdogan wants to change the way Turkey is governed, abolish the post of prime minister and significantly extend his own powers. Polls suggest the referendum result will be tight. He needs the support of Germany's Turks.

President Erdogan has significant support in the diaspora, but there's also opposition

Though, as the singers pause and the players lay their fat-bellied Turkish guitars on the floor, few here tell us they'll dance to his tune.

"Actually there is huge opposition to the Erdogan regime in the Turkish community here," says Filliz, "but there's nearly no coverage in the media about it. So Germans think that every Turkish person is an Erdogan supporter - which is simply not the case."

But there is also significant support for him among the diaspora.

Between 50% and 60% of German Turks who voted in elections over the last four years supported Mr Erdogan and his party.

And there were cheers for his foreign minister on the campaign trail in Hamburg on Tuesday.

Nazi row

Mr Erdogan has dispatched several of his cabinet to Germany, and a furious diplomatic row ignited after German authorities cancelled a number of planned rallies citing security or technical reasons.

Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu, for example, spoke from the Turkish consulate in Hamburg after the city authorities closed his original venue after saying that the fire alarm system wasn't working.

A furious Mr Erdogan likened Germany's actions to those of the Nazis, provoking outrage at the highest level in Berlin.

The Turkish foreign minister addressed crowds from the Turkish consular residence in Hamburg, after German authorities banned a scheduled rally

On Thursday morning, Angela Merkel's indignation was still palpable as she addressed the German parliament.

"Comparisons with Nazi Germany," she said "always lead to misery, to the trivialisation of crimes against humanity committed by National Socialism. We will not tolerate this under any circumstances."

The comparisons, she said, must stop. But the diplomatic row shows little sign of abating.

A sleek convoy of black cars drove through a grey Berlin morning on Wednesday: crisis talks between foreign ministers that yielded little result.

Despite pressure from Berlin, a journalist from the German newspaper Die Welt is still in a Turkish jail - the German government has failed as yet to secure consular access to Deniz Yucel - and Ankara insists it will continue to campaign on German soil.

Germany should allow that to happen, says Bekir Yilmaz, the president of the Turkish community in Berlin. Mr Erdogan was wrong, he says, to invoke the Nazi past.

There is anger in Germany over the detention of the Die Welt journalist Deniz Yucel in Turkey

However, he insists: "People should have the right to campaign freely here. Then voters can decide what's right or wrong. Germans have to accept that."

Commentators point out that, for President Erdogan, provoking a row with Germany is simply a calculated election technique - positioning himself against the West and thereby securing votes from right-wingers at home.

"Of course he benefits from the controversy," says Ralph Ghadbhan, who has studied the Turkish diaspora for decades.

"It's his intention. He sees Germany as a colony and he proved that when he said recently if the German government stops him from campaigning here then they will be confronted with an uprising."

New divisions

The relationship between Ankara and Berlin is often stormy. There were furious exchanges last year after German comic Jans Bohmermann insulted Mr Erdogan with a satirical poem. And there were protests after the German parliament officially declared the massacre of Armenians by Ottoman Turks during World War One a genocide.

But this has strained diplomatic relations to the limit, and there is much at stake. It is perhaps telling that this time neither Mr Erdogan or Mrs Merkel has raised the subject of the migrant deal between the EU and Turkey, which the German chancellor largely orchestrated.

Under the deal, Turkey holds back migrants in return for billions of euros. The deal was controversial, some say not that effective. But arguably it is one of the ties that continue to bind the two sides together - just.

The singers in the Turkish choir worry about the impact of the row on their own community here, and on how Germany perceives them.

Old music, new divisions. And still that bitter tone persists. Germany, Ankara warned last night, must decide whether it is a friend or a foe.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published8 March 2017

- Published5 March 2017

- Published24 February 2017

- Published1 March 2017