Crimea: The place that's rather difficult to get into

- Published

Russia hopes a bridge to Crimea will solve many problems

Three years after Russia annexed Crimea, a move bitterly contested by Ukraine's government, the region remains in a state of flux. It's difficult to get into, and for many people, it's difficult to know where it's going.

At Kiev International Airport, I hand my passport to a border guard.

"Purpose of visit?" he asks.

"Journalism. I'm with the BBC."

He pauses. He studies my passport. He seems to be checking a list. He goes to pick up a telephone and asks a question. He does not realise I can hear.

"You remember that pro-Russian journalist from the BBC? Was his surname Rosenberg?"

Another pause.

"It wasn't? OK, thanks." He hangs up. He stamps my passport and returns it.

"Welcome to Ukraine!" he smiles.

Those pauses at passport control are an indication of the current tension between Moscow and Kiev - a relationship clouded by enmity and suspicion.

Our BBC team is only passing through Kiev. Our final destination is Crimea, the Ukrainian peninsula annexed by Russia three years ago.

Parades marked three years since Russia annexed Crimea

For journalists based in Russia, there are faster ways of reaching the Crimean peninsula. Board a plane in Moscow and two hours later you can be in the Crimean capital Simferopol. Ukraine, however, warns foreign nationals that anyone entering "temporarily occupied Crimea" without Kiev's permission and without crossing an official Ukrainian border may be banned from future entry to Ukraine.

We're taking the longer route.

Direct flights from Russia to Ukraine stopped in October 2015. We flew from Moscow to the Belarusian capital Minsk, then on to Kiev. Ahead of us is an eight-hour road trip to Crimea.

First, we visit the Ukrainian Migration Service in Kiev to obtain the "dozvil" - a document issued by the Ukrainian authorities permitting travel to Crimea. Three hours later, permission slips in hand, our long car journey south begins.

Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 was a watershed moment. It pushed Moscow and the West to the brink of a new cold war. Three years on we are travelling to Crimea to gauge the mood.

It is dark by the time we reach the final Ukrainian checkpoint before the peninsula. Ukraine does not call the Kalanchak crossing a border - officially, it is a "control point for entry and exit". We show our passports and dozvils. Minutes later we are waved through.

The no-man's land between the Ukrainian and Russian checkpoints is tiny - no more than 50m long. We stop here to change cars - our Kiev driver will turn back. A driver from Simferopol has come to meet us.

On the Russian side this is called the Armyansk crossing. As far as the Russians are concerned, it is an official state border. We show passports and visas and fill out immigration cards. Our documents are in order, but we are asked to wait. The appearance here of British journalists has raised official eyebrows.

A young man in civilian clothes approaches me. "Come with me, please," he says, "I'd like to have a chat."

We enter a small room and sit down at a table. He checks my phone to make sure I am not recording our conversation.

Then come the questions. Lots of them.

"What mission have your editors set you? What will you be filming? How will you be saving your material, on computers or hard drives? What SIM card will you be using in Crimea? As the correspondent, will you be making notes each night about what you have filmed? Can you show me some of the photos on your phone? Where will you be staying? Why didn't you fly direct from Moscow?"

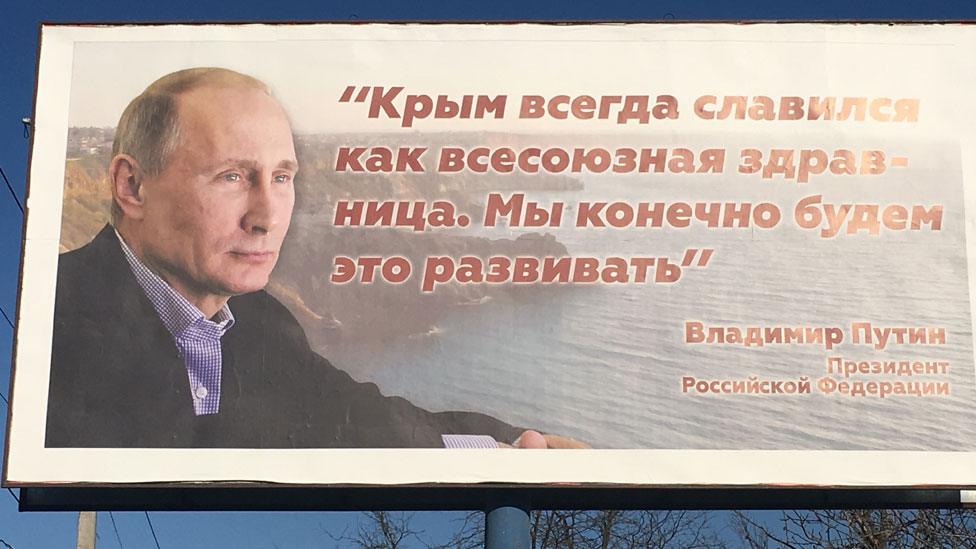

Crimea has a wide variety of Vladimir Putin murals and posters

My interrogator notes down my answers on a piece of paper. His questions are not limited to Crimea.

"What street do you live on in Moscow? What is the nearest Metro station to your home? What does your wife do for a living? You've been in Russia a long time. Have you ever considered applying for a Russian passport?"

"My British one suits me just fine," I reply.

"What do you think of English cuisine?" he asks, adding, "I like Jamie Oliver. Although I consider he uses too much oil."

The questioning lasts an hour. Then the official escorts me back to the van. I ask for his name.

"I have no name," he replies, "only a rank."

The inquisitive young man with "no name, only a rank" invites my colleagues for similar conversations.

Three hours pass. Interrogations over, we are still not free to go. We spend the night in the van waiting for Russian customs officers to process our papers and allow our TV equipment through. Ten hours after arriving at the Armyansk crossing, we finally clear the checkpoint.

Simferopol is the administrative centre of Crimea. The name of our hotel is the "Ukraine". But three years after annexation, the town feels Russian. Most of the cars have switched to Russian number plates, brand new buses manufactured near Moscow have taken to the roads. And, peering down from billboards is the Russian president with some of his choicest Crimea quotations - just to remind everyone who is in charge.

In this poster Putin promises to boost Crimea's spa facilities

"Crimea was famous for being the spa of the Soviet Union," declares Vladimir Putin in one poster. "We will, of course, develop this."

"All Russian army social programmes will be extended to Sevastopol and the Black Sea Fleet," he promises in another.

Near our hotel, the wall of a building is covered with a giant painting of President Putin dressed as a sailor and the words: "Crimea belongs to all of us".

As far as retired teacher Olga Koziko is concerned, the more Putin in Crimea, the better.

"Crimea is a place where people support Putin," Olga assures me. "We just adore him. He's our hero. I even have a T-shirt with Putin and the words: 'In Putin We Trust', like 'In God We Trust.' Thanks to Putin, Russian soldiers came to protect us."

Voices from the annex

On 22 February 2014, Ukraine's pro-Moscow president Viktor Yanukovych fled the country after what he - and his Russian allies - called an "illegal coup" in Kiev. On 27 February masked men in unmarked uniforms appeared in Simferopol. Armed with Russian weapons, they seized government buildings, the parliament, the airport and blocked Ukrainian army bases. This mysterious military force picked up a variety of nicknames, including The Little Green Men and The Polite People.

Today Moscow admits the soldiers were from Russia's secretive Special Operations Forces (the SSO). President Putin subsequently signed a decree making 27 February an annual celebration in Russia - "Special Operations Forces Day".

Following a hastily organised referendum, it was announced that more than 95% of people who had taken part had voted for Crimea's "reunification" with Russia. The referendum was not recognised by the international community. To the outside world, Russia had grabbed a piece of Ukraine.

A statue honouring The Little Green Men has been erected near the Crimean parliament building. It depicts a young girl handing flowers to a man with a gun. The inscription reads: "To The Polite People from the grateful people of Crimea."

Russia has shrugged off international condemnation over Crimea

This is how Moscow wants to be seen here: as a force for good, protecting the people of Crimea from violent Ukrainian nationalists. In 2014 Russia's state-controlled media characterised the new Ukrainian government as "fascists", "neo-Nazis" and an "illegitimate junta''. Olga uses similar language as she recalls the past.

"Without Russia, a lot of people would have been killed here," maintains Olga. "Ukrainian Nazis said Crimea would either be part of Ukraine or empty. People would have been oppressed. Perhaps even put in concentration camps."

There is absolutely no evidence to substantiate Olga's claims.

Many of those in Crimea who welcome Moscow's rule see the bloody conflict in eastern Ukraine as confirmation that Russia is a safer home. They discount evidence that unrest in the Donbass was incited and bankrolled by Moscow.

Out on the street I get chatting to a pensioner called Nadezhda. Until recently her sister had been living in Luhansk, one of the self-proclaimed separatist republics in eastern Ukraine.

"Life in Luhansk is terrible," Nadezhda says. "So I moved my sister to Crimea. I will do everything to make sure that kind of violence doesn't break out here."

There is another reason why Nadezhda, an ethnic Ukrainian, trusts Moscow more than Kiev - it is out of nostalgia for Soviet times, when she regarded Moscow as her capital. Nadezhda describes Crimea joining Russia as "a return to the Soviet Union. Our generation was, is and will always be in the USSR. We will die in the Soviet Union."

People pass a mural of Putin at the wheel of a ship

Nostalgia and fear are powerful feelings. But they are not enough to sustain pro-Russia sentiment in Crimea at the level of 2014.

Severing ties to Ukraine has brought problems. With economic links to Ukraine cut, the only way of keeping the peninsula supplied is by sea or air. That means higher prices. Moscow insists that will change once it has completed a road and rail bridge linking Crimea to the Russian mainland. The bridge is a multibillion-dollar statement that Moscow is here to stay.

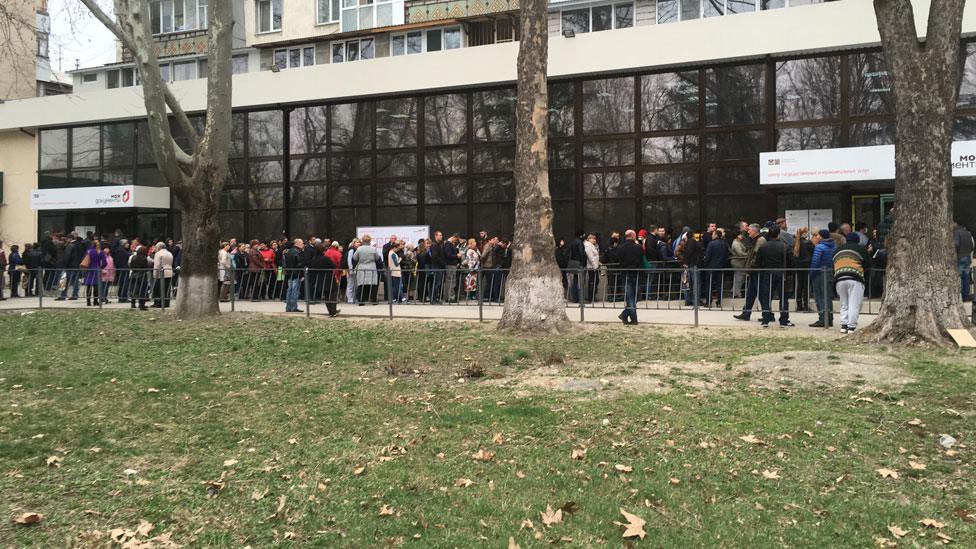

As well as higher prices, there is Russian red tape.

I visit a document registration centre in Simferopol. More than two hundred people are queueing outside. They have come to exchange Ukrainian documents, like deeds for apartments, for Russian ones. Some people, like Alyona, have been queuing here all night.

"Life hasn't got better or worse," Alyona tells me, "We're still standing in lines, like we always used to. Maybe some people had big expectations three years ago. But I don't believe in miracles."

People queue for a long time to change Ukrainian documents to Russian ones

I ask Alyona if she could imagine Russia handing Crimea back to Ukraine.

"Nothing would surprise me any more," she laughs. "I wouldn't be surprised if we suddenly ended up as part of Turkey. To be honest, I don't care if we're with China! The most important thing is that there is no war.

"I've learnt that your life can be turned upside down in a day. And there is nothing you can do about it. We're like pawns on a chessboard. They're playing with us. Today our place is in Russia. And tomorrow? Who knows. Maybe that's for the best: if we knew, we might have a heart attack."

Across town, I meet Nadia. She is complaining to me about potholes.

"Where I live there are potholes everywhere," Nadia says. "People have been hurting their legs. I've written to the authorities asking them to do something. They haven't lifted a finger."

Nadia's disappointment extends further than pavements and roads.

"Many people here were happy, but there is disillusionment now," she tells me, "because there is no investment and salaries and pensions are small. My pension is 8000 roubles ($140; £112) a month. Just about enough to cover utility bills and the medicines I need."

I am talking to Nadia beside the statue of Ukraine's most famous 19th Century poet, Taras Shevchenko. It is Shevchenko Day and a group of twenty people have come here with flowers to mark the poet's birthday. Russian police have come, too - with cameras. They are filming everyone, including us. In Russian Crimea, public expressions of Ukrainian pride attract special attention.

Nadia is an ethnic Russian, but she is wearing a small Ukrainian flag.

"In my soul, Crimea is still part of Ukraine," Nadia tells me. "I'm here because this statue is the last symbol of Ukraine left in Crimea."

Crimea's economy has struggled to adjust

A woman called Lidiya overhears our conversation. She is furious.

"It was the Russian Empress Catherine the Great who built up Crimea," says Lidiya sternly.

"Well, if you're going to bring up history, we could go right back to the days of the Crimean khans," retorts Nadia.

Lidiya switches to modern history.

"Three years ago America was planning to station soldiers in three schools in Sevastopol," she claims. "Nato troops wanted to be in Sevastopol. Crimea would have been wiped from the face of the earth."

"How do you know that?" I ask.

"I read it in the internet," she replies.

"Does that make it true?"

Lidiya changes tack.

"If people think they live badly in Crimea today, let them go and live in the Donbass in eastern Ukraine. They will be crying to come back here."

Umer Ibragimov is desperate to find what happened to his missing son

We drive to the town of Bakhchysarai in central Crimea to meet Umer Ibragimov. Umer, a Crimean Tatar, is desperate for information about his son Ervin. In May 2016 Ervin was abducted late at night. CCTV cameras caught the moment he was seized by men in uniform and bundled into a vehicle.

"I've written to everyone asking for help," Umer tells me, "from the bottom levels right up to the president. But there has been no information about my son."

Ervin Ibragimov was a member of the executive board of the World Congress of Crimean Tatars. Since annexation, the Crimean Tatar community has come under pressure. Its elected representative body, the Mejlis, which had opposed the 2014 referendum on joining Russia, has been ruled an "extremist organisation" and banned.

Human rights group Amnesty International accuses the Russian authorities of "systematic persecution" of Crimean Tatars. This month the European Union's foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini concluded that "the rights of the Crimean Tatars have been gravely violated". Moscow denies the accusations.

Over piping hot tea, Umer tells me the story of his family. In World War Two, his father had fought in the Red Army.

"He was wounded and came home," Umer says. "Ten days later, all Crimean Tatars were deported from their homeland."

It was Josef Stalin who had ordered the deportation - an act of collective punishment and paranoia. The Soviet dictator suspected Crimean Tatars of collaborating with the Nazis. More than 230,000 people were forced on to cattle trains and transported to Central Asia.

"My mother and father told me later they'd be given just 15 minutes to gather their belongings," recalls Umer.

Umer grew up in Soviet Uzbekistan. Conscripted into the Soviet army in the late 1970s, he spent a year fulfilling his "internationalist duty" fighting in Afghanistan.

Umer looks at a photograph of his missing son.

"There is no justice," he says.

And yet this Crimean spring feels calmer than three years ago. While Russia and the West argue over sanctions, sovereignty and borders, it seems that most people here are just trying to get on with their lives, trying to adapt.

The region's traditional tourist appeal has diminished

"Everything calmed down," artist Svitlana Gavrilenko says. "Everyone who used to be 'pro' something - either pro-Russia or pro-Ukraine - everybody calmed down."

Three years ago Svitlana had opposed annexation. Today her perspective has changed.

"A lot of small and medium-sized businesses fell apart after Russia came because they were all connected to Ukraine. Now they have reconnected to Russia and China. If we become a part of Ukraine again, we will need to solve all this stuff again. Everyone's life is going to be screwed up again."

In the Black Sea resort of Yalta I find the promenade packed with people enjoying a seaside stroll in the sunshine. The sound of the waves crashing on the shore mixes with jazz chords from street musicians. From the conversations, there is an overriding sense of a population desperate for peace.

"Many people in Crimea still love Ukraine," Rodion says. "Russia and Ukraine are too similar, their peoples too inter-connected to feel bad about each other."

Rodion believes "it's not completely impossible" that Crimea would one day return to Ukrainian rule.

"Nobody ever imagined it would become a part of Russia," he says, though he resents Western leaders who demand the peninsula's return. "Crimea is not just a thing to be given to one country or another. It's a place. It's the people who live here. It's history. It's many things that cannot be bought or inter-changed."

Svitlana Gavrilenko believes that the changes that took place here three years ago are irreversible.

"I don't think Russia in its modern state, with Putin at the top, could ever give Crimea back," she tells me. "They made so much effort to connect it. They suffered through all these sanctions just to have Crimea. Why would they give it back?"

Pictures are copyright BBC and Getty Images

- Published1 December 2016

- Published14 August 2016