Russia and the West: A century of subversion and suspicion

- Published

Vladimir Putin insists he did not interfere with the election of President Trump

The claim that the Kremlin sought to influence America's presidential election is only the latest chapter in a much longer story of mistrust between Russia and the West.

Espionage - the stealing of secrets - is a well-trodden path for both sides, but far more sensitive is the notion of subversion, trying to influence political life by sowing dissent and supporting opposition.

Both Russia and the West claim the other has been practising subversion for at least a century.

Russian subversion is the talk of Washington at the moment, but Moscow has its own narrative.

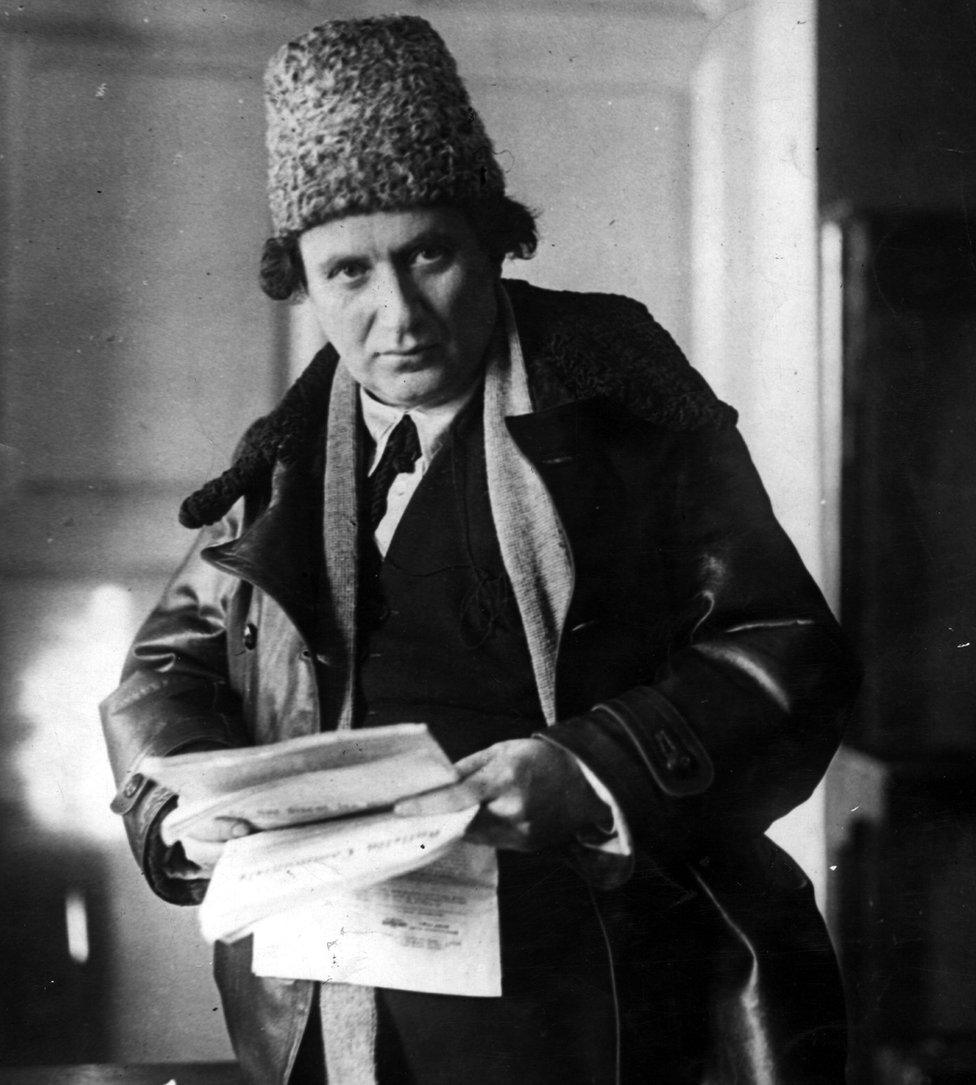

It begins 100 years ago, when Britain was determined to roll back the 1917 Bolshevik revolution. Enter a colourful array of characters linked to MI6, notably Sir Paul Dukes and Sidney Reilly ("Ace of Spies").

But it is the Lockhart Plot which is particularly remembered in Russia - although barely known in Britain.

'Evil intentions'

Named after British diplomat Robert Bruce Lockhart, who was stationed in Moscow, it involved paying Latvian soldiers to launch a counter-coup.

"The shadow of these events still hangs over our relations," says Prof Evgeny Sergeev, from the Russian State University for Humanities.

"It was used by Soviet propaganda as the symbol of all those evil intentions to overthrow the Bolshevik government."

The Bolshevik government's reaction was to strengthen its secret police to protect against outside interference and to send its spies abroad to discern the plans of others.

Back in Britain during the 1920s, the government feared worldwide Bolshevik revolution. Concerns centred on The All Russian Trade Co-operative Society (Arcos) in London.

In 1924, the Daily Mail printed a letter - later dismissed as a fake - purporting to be from senior Soviet official Grigory Zinoviev

Britain's intelligence services were convinced it was not only a nest of spies but the epicentre of subversive activity - spreading propaganda and supporting strikes, amid fears that "Moscow gold" was supporting "terrorist groups" in the British Empire.

A message from the Communist International known as the Zinoviev letter helped fuel that idea - even though it was fake.

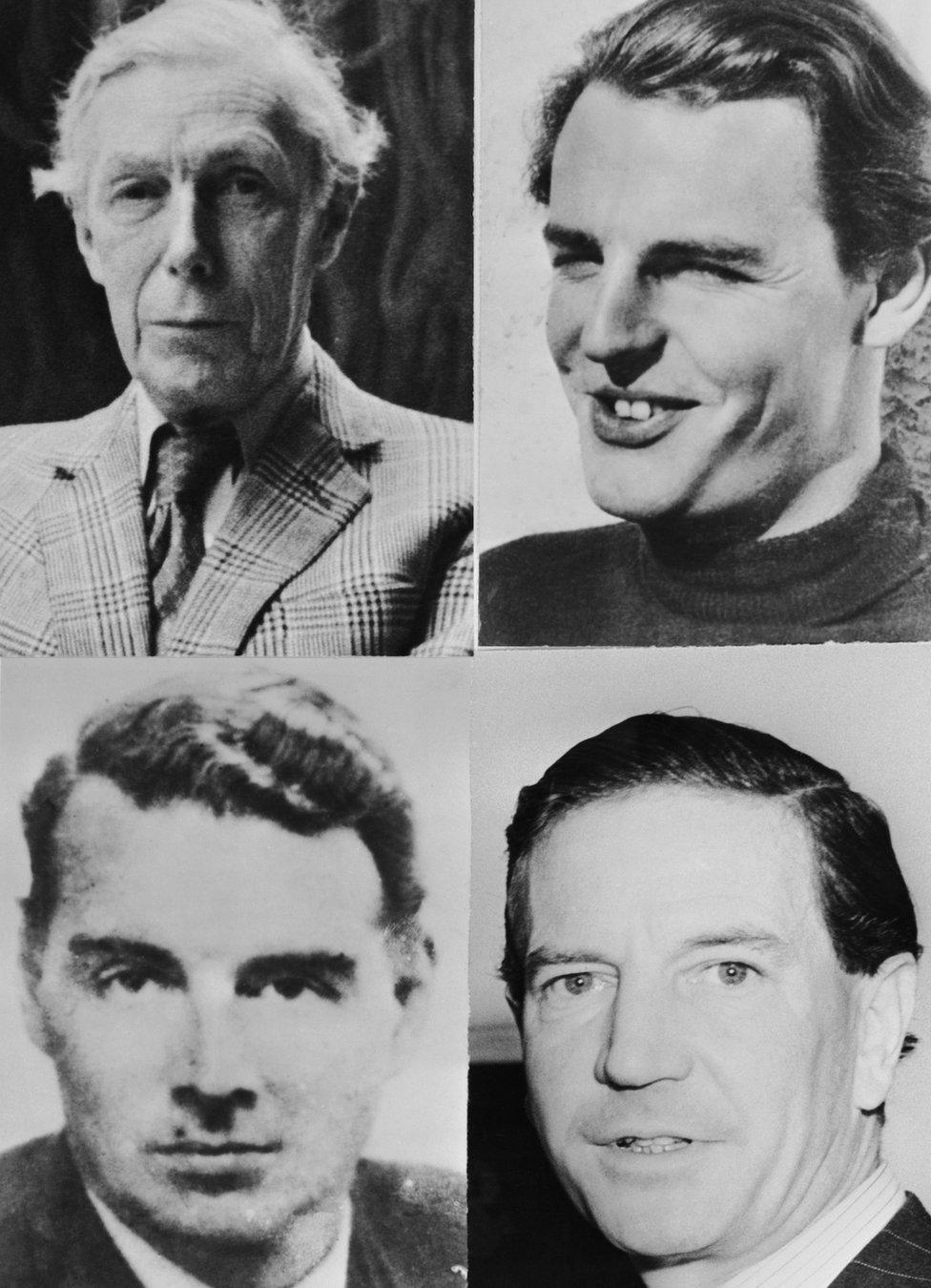

Arcos was closed in a chaotic raid, but it was not long before Soviet intelligence pulled off one of its greatest coups - recruiting a group of Cambridge graduates who would work their way into the heart of the British establishment.

Four members of the Cambridge spy ring were initially identified: Anthony Blunt (top left), Donald Duart Maclean (top right), Kim Philby (bottom right) and Guy Burgess (bottom left)

Britain also seems to have had its own plans.

In 1937, Fitzroy Maclean took up a diplomatic posting in Moscow, witnessing the show trials in which Stalin purged his opponents and travelling widely across the Soviet Union.

This gave him an idea which he wrote up on his return to the Foreign Office in 1939.

The long game

Oddly, his memo - originally marked Top Secret - has appeared and disappeared from the British archives in recent years. But Moscow had known about the content for decades.

Fitzroy Maclean's classified memo was leaked to the Russians decades ago

I learned this from Todor Boyadjiev, a retired deputy head of Bulgarian intelligence, who says Russian colleagues showed him the memo and further plans based on it.

Boyadjiev says MI6 developed a plan codenamed Lyautey, named after a French general.

The story goes that the general asked his gardener to plant some trees to provide shade. The gardener protested they would take decades to grow, to which the General replied there was no time to lose.

Britain's Lyautey plan, Boyadjiev says, was a long-term effort to fragment the Soviet Union by stirring up unrest among religious and ethnic minorities over 50 years.

We don't really know whether it was put into effect, since if there are any related files inside MI6, they remain secret.

But in one sense it does not matter. Soviet spies smuggled out the memo, and knowledge of the subversion plan fuelled existing tensions.

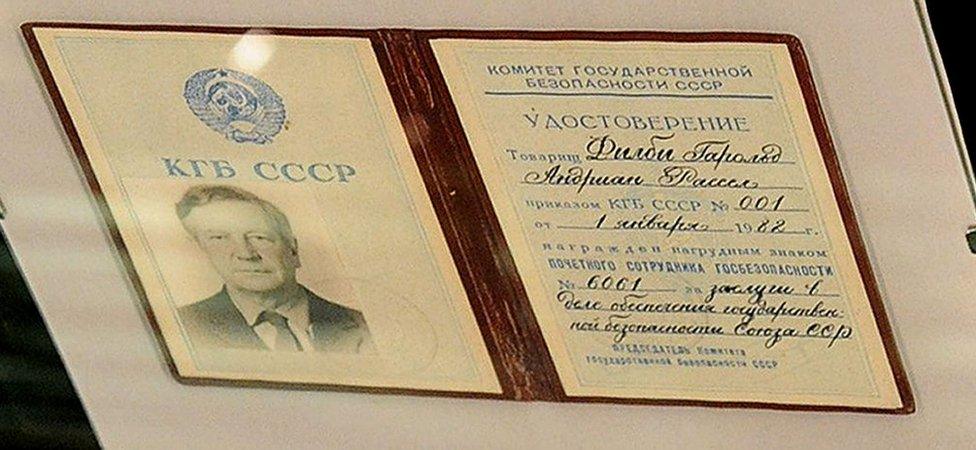

Kim Philby's KGB ID card was displayed at an exhibition highlighting 90 years of Russia's Foreign Intelligence Service in Moscow in 2010

That was probably boosted by Kim Philby, who told Moscow about CIA and MI6 operations in the early Cold War to drop agents into places like Albania, the Baltics and Ukraine, to stir up unrest and pull them away from Moscow's grip.

Philby and the other Cambridge spies were engaged in espionage, but subversion was the unintended consequence of their actions, as their betrayal led British intelligence to turn in on itself, and increased mistrust in the establishment.

'Mentality of a besieged fortress'

Russia's Cold War subversive activities focused on so-called "active measures" - attempts to influence debate often delivered via "agents of influence", including politicians and journalists.

The fear of subversion and hunt for Russian spies became a powerful narrative in the West.

Talk of subversion did not end with the Cold War. Moscow would resurrect the narrative that it was the target of Western plots.

Find out more

Gordon Corera presented Subversion: East on BBC Radio 4 on Friday 24 March at 11:00 GMT. Subversion: West will be on BBC Radio 4 on Friday 31 March at 11:00 GMT.

Or you can listen to both programmes after broadcast on the BBC Radio 4 website.

First it was the expansion of Nato to its borders.

"That was already the origin of real suspicions on our side," General Vyacheslav Trubnikov, head of Russia's Foreign Intelligence the SVR from 1996-2000, told me in Moscow.

General Vyacheslav Trubnikov says Russia felt threatened by Nato expansion

"The United States [and] its allies considered themselves to be victorious in this Cold War. Russia, as a defeated side, should stick to the rules and manners dictated by the victorious side."

The overthrow of pro-Moscow governments in neighbouring states like Georgia and Ukraine - the so-called colour revolutions - were also seen in Moscow as the work of foreign covert assistance, sometimes through non-governmental organisations, rather than as popular uprisings.

"I don't believe it's only about propaganda," says Andrei Soldatov, author of The Red Web, and a leading writer on Russia's security services.

"For them it's real. It reflects their mentality of a besieged fortress."

Concrete evidence?

The notion of subversion has created a powerful tool in the Kremlin's own story of being under siege and needing to resist outside influences, which it used to justify both a tightening of state control at home and activities abroad.

In 2011, protests emerged in Moscow itself and outside interference was blamed once again. Vladimir Putin was said to have been especially angry at comments by Hillary Clinton.

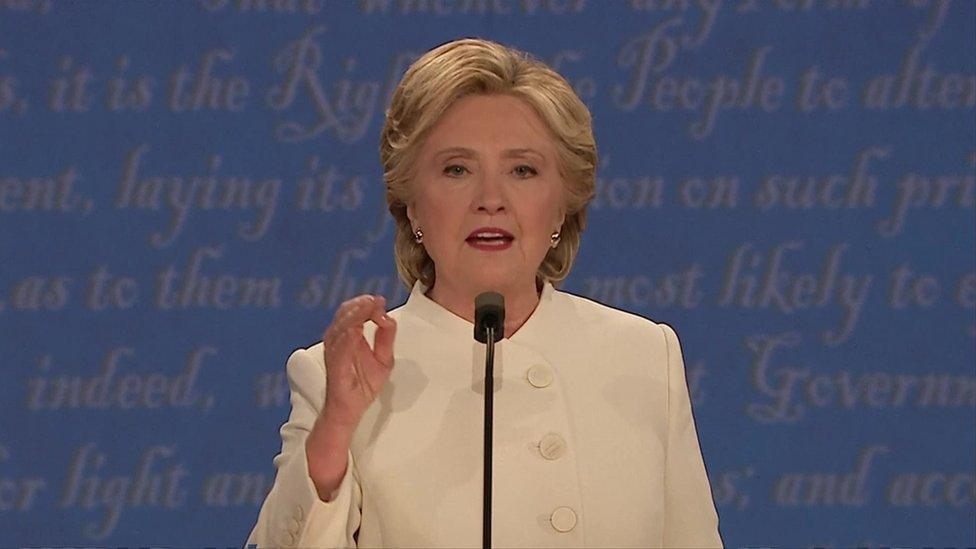

Hillary Clinton accused Donald Trump of being "a Putin puppet" during the presidential debates

Last December, she drew a link between those events and Russian intervention in her election campaign. "Putin publicly blamed me for the outpouring of outrage by his own people, and that is the direct line between what he said back then and what he did in this election," she claimed.

The notion of Russian subversion in the West had largely subsided at the end of the Cold War - until the US election.

Now each side perceives the other as actively engaged in such activities once again.

"I have no doubt that Vladimir Putin does indeed [incorrectly] believe that the US government - probably led by the CIA - is interested in somehow running covert action which would result in regime change in Moscow," argues Steve Hall, who ran the CIA's Russia operations until he retired in 2015.

"On the West's side, I think things are a little more concrete. The US intelligence community agrees there is evidence that the Russians were indeed involved in a multi-pronged influence operation."

Perceptions matter but so does evidence.

If Moscow can be proved to have run an operation with a decisive influence in the election, then it may well be regarded as the most far-reaching act of subversion ever seen.

- Published20 March 2017

- Published20 March 2017

- Published14 September 2018

- Published18 March 2017

- Published4 November 2016

- Published4 April 2016