Why Rome sends trains filled with rubbish to Austria

- Published

How Rome's rubbish is powering Austrian homes

Rome's rubbish is helping to power Austrian homes - and it gets to Austria by train.

Rome has been struggling to cope with a rubbish crisis and Austria has spare capacity at a waste-to-energy plant near Vienna.

So a deal has been struck. The Italians are paying Austrian company EVN to dispose of up to 70,000 tonnes of Roman household refuse this year.

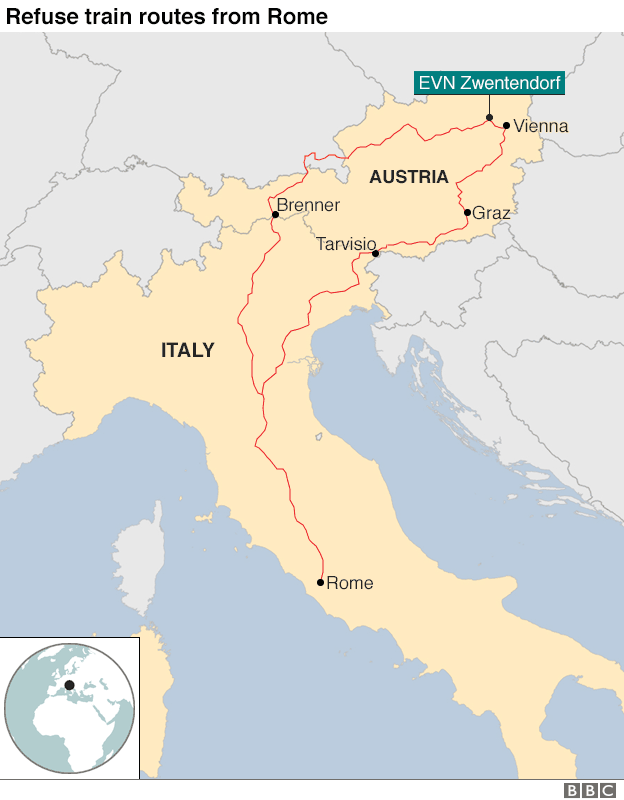

The waste is transported by train through northern Italy, over the Alps and ends up at the EVN thermal waste utilisation plant at Zwentendorf on the Danube.

Up to three trains a week arrive at the Zwentendorf plant. Each carries airtight containers loaded with around 700 tonnes of Roman household waste.

The refuse is incinerated and converted into hot flue gas, which generates steam. The steam is delivered to a neighbouring power station, where it is converted into electricity, which is used to power 170,000 houses in the province of Lower Austria.

How Norway turned rubbish into fuel

It may seem counter-intuitive to carry rubbish over 1,000km (620 miles) before disposing of it, but it is part of efforts in the European Union to make cities reduce the amount of waste that goes into landfills.

"It is not crazy," insists Gernot Alfons, head of the EVN thermal waste plant. For him it is an environmentally friendly solution and the rubbish trains are key.

"The other alternative would be to put this rubbish into landfill, which creates a lot of methane emissions that create a lot of impact in terms of CO2 emissions.

"It is much better to transport this waste to a plant which has a high energy efficiency like ours."

The trains travel more than 1,000km to Zwentendorf in eastern Austria...

...where the waste is sorted and incinerated before being used to power thousands of homes

So what has gone wrong with Rome's waste disposal?

Even in elegant districts like Prati, near the Vatican, it is not hard to see that the city has a rubbish problem.

Overflowing communal bins for both household waste and recycling are a common sight, and a lot of Romans are very unhappy.

"I think it is outrageous," Claudia Grassi, a resident of Rome told me. "The beautiful town of Rome is being insulted. It is like a beautiful woman that has been wounded again and again."

Rubbish overflows in the elegant streets of Prati near the Vatican

Antonio La Spina, professor of sociology and public policy at Rome's LUISS University, says the city produces more waste than it can cope with.

"One factor is the remarkable amount of waste that is produced per capita in Rome. Another is that the share of (separated) waste is increasing.

"That's a good thing in general, but not if the authorities aren't ready to deal with it all - which they aren't.

"Another problem is the fact that the landfills are full - and some are already a big environmental problem, and need to be closed."

Rome's landfill sites are so full, he says, that the authorities have not only had to look beyond the region, but beyond Italy, to dispose of their waste.

Where there's muck, there's brass

But it is not just the lack of space. The rubbish problem is also political.

Rome Mayor Virginia Raggi's vow to tackle the rubbish crisis has hit the buffers

Waste disposal and other public services in Rome have been plagued by more than mismanagement.

In 2014, an investigation known as Mafia Capitale laid bare corruption and tainted bidding in city services, including rubbish collection.

Rome's Raggi finds it tough at the top

When in Rome shake up the politics

Rome's new Mayor Virginia Raggi, from the populist Five Star Movement, came to power last year promising to clean up the city.

But she ran into trouble almost immediately.

The person she appointed as the city's rubbish tsar, Paola Muraro, was forced to resign after it emerged she was under investigation for alleged wrongdoing during her 12-year stint as a consultant to Rome's rubbish collection agency, AMA.

Not a pretty sight: Rome's Campo de' Fiori is a mess for several hours a day

Ms Muraro has denied allegations of impropriety. But Mayor Raggi is under pressure.

In Campo de' Fiori, one of Rome's most attractive markets, rubbish piles up on the cobblestones almost every afternoon, amid the flower and vegetable stalls.

Rubbish collectors eventually arrive to clean it up, but Vladimir, who works at a local restaurant on the square, shakes his head.

"It is disgusting here for two or three hours a day, until they clear it up. Tourists who come here are in shock. In the centre of a European capital, this is not normal."

- Published8 September 2016

- Published5 June 2010

- Published24 September 2013