Is France's Socialist Party dead?

- Published

After suffering a crushing defeat in the first round of the French presidential election, can the party of Francois Mitterrand survive?

Socialists are romantics.

They love their icons and their rituals.

They get attached to history.

They believe in the continuity of the fight.

They see themselves carrying a torch lit first by the heroes of the past, in their beards and their bowlers.

For Socialists, the party has a meaning that goes beyond the ups and downs of electoral fortune.

It structures their thoughts, and it conditions their friendships.

In a way that transcends mere politics, it plays a real part in their lives.

To live in a world where the party no longer mattered - that would be a truncated, an empty form of existence.

And yet in France today - if you believe some of the commentators - it is the very survival of the Socialist Party (PS) that is now at stake.

And the faithful are bereft.

The signs of mortality are certainly strong.

In the presidential election, the Socialist candidate, Benoit Hamon, was knocked out in round one, with just 6.36% of the vote.

The score was the lowest achieved by a Socialist candidate since Gaston Defferre's 5.1% in 1969.

The PS's Benoit Hamon received less than 7% of the vote in the first round of the election

Worse, Mr Hamon was not just overtaken, he was trounced by another candidate of the left, Jean-Luc Melenchon, of the radical La France Insoumise (France Unbowed).

Mr Melenchon got 19.6% and more than seven million votes - three times the PS score.

Today, he enjoys a popularity nationwide that far exceeds that of any Socialist leader.

And on the party's other flank, there is another danger: the new presidency of Emmanuel Macron.

Mr Macron may not look like a Socialist, but the left is where his political feelings lie.

That is why he chose to work under Francois Hollande, a Socialist president.

The maps that show how France voted and why

French ex-PM Manuel Valls wants to be Macron MP

BBC Newsday: Socialists say how they got it wrong

Now that Emmanuel Macron has his own party up and running - La Republique en Marche (REM) - there is suddenly another powerful rival vying for votes.

The PS finds itself caught in a classic casse-noisette (nutcracker).

On both sides are powerful new "movements" set up in deliberate counterpoint to the old party system.

At the forthcoming parliamentary elections, if voters want social-radical, they'll pick Mr Melenchon.

If they want social-liberal, they'll pick Mr Macron.

The space in the middle is shrinking to insignificance.

All of which would be more easily surmountable, if the Socialist Party itself was in any shape to mount a comeback.

But the PS is torn between factions that themselves reflect the changing outward perspective.

The far right Marine Le Pen beat the Socialist and radical left candidates

On the one hand, there are those figures willing to work in alliance with Mr Macron's REM.

The most extreme example is former Prime Minister Manuel Valls, who has described the PS as "dead" and more or less torn up his party card.

At the other end are leaders - such as the ex-candidate Benoit Hamon - who dream of forming a new left-wing opposition to the Macron presidency, in alliance with ecologists and Mr Melenchon's radicals.

And in the middle are people who argue for a watching brief, supporting or opposing Mr Macron according to the issue.

The point is that no clear line is emerging from the top, so the PS is going into the legislatives not just demoralised but also leaderless and incoherent.

Small wonder the party fears a wipeout.

For some analysts, what is happening is the end of a historical cycle that goes back nearly 50 years - to the 1969 annihilation, in fact, of Gaston Defferre and the regenerative shock that gave to the French left.

In 1969, the Socialist Party in France did not exist.

Instead, there was the French Section of the Workers International (SFIO), which was Mr Defferre's party, plus smaller parties linked to Francois Mitterrand and Michel Rocard.

And of course, the biggest party of the left - the Communists.

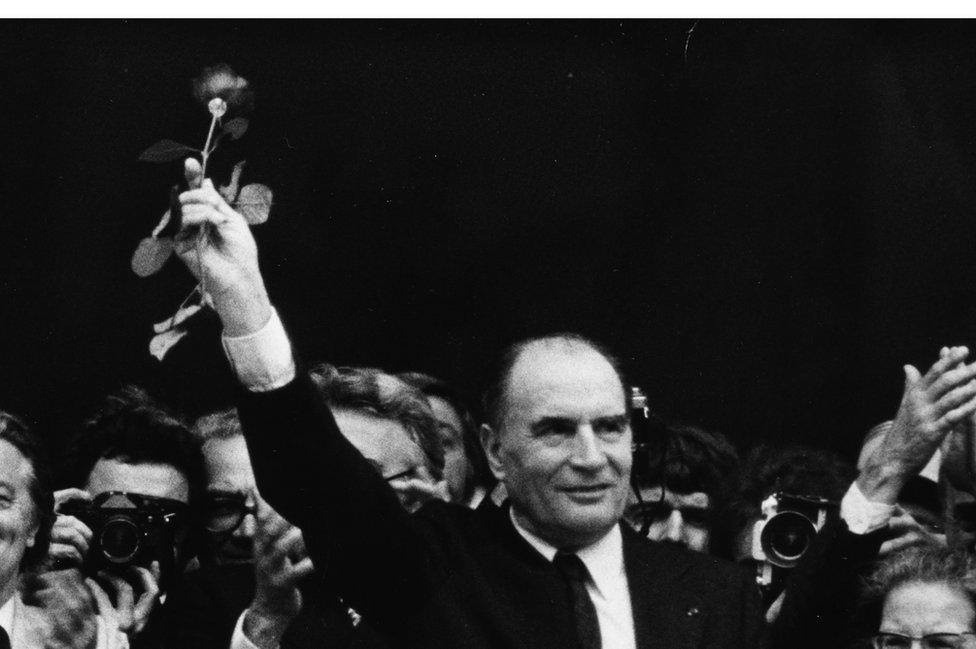

But the 1969 result triggered a series of changes, culminating in the much-mythologised Congress of Epinay two years later, in which Mr Mitterrand engineered a union of the disparate groups and founded the modern-day PS.

By entering a strategic agreement with the Communists - and introducing them to his government in 1981 - he then succeeded in emasculating the far left.

And the course of French socialist history was set for a generation.

Socialist Francois Mitterrand won the presidency in 1981 and 1988

But at the heart of the Mitterrand legacy was a contradiction - between dogma and reality, utopia and the free market.

Mr Mitterrand, with his imposing personality and cynical use of the powers vested in him as president, was able to surmount that gap.

But no-one since has lived up to his example.

All that successive leaders could do was paper over the cracks.

Mr Hollande was a master of this art of political "synthesis".

As long as a form of words could be adduced, then all sides were satisfied and the grail of Socialist unity was assured. Till now.

So is this historic phase now drawing to a close?

One argument says yes.

The old party system is already breaking down.

Social media and post-modern politics are changing the relationship between voter and candidate.

Party structures are cumbersome and unreactive.

Other parties in history have disappeared.

Once upon a time there was a French Radical Party that was one of the most powerful in the land.

Now, it barely registers. Ditto the SFIO.

The PS could similarly shut down, many argue, and the world of political ideas would be none the poorer.

But let us not be hasty.

New politics may be all the rage today, but who knows what lies ahead?

Sentiment and tradition still count for something - and the rose and the fist was a mighty icon.

The PS is not dead yet.

- Published15 May 2017