Should Russia's new Armata T-14 tanks worry Nato?

- Published

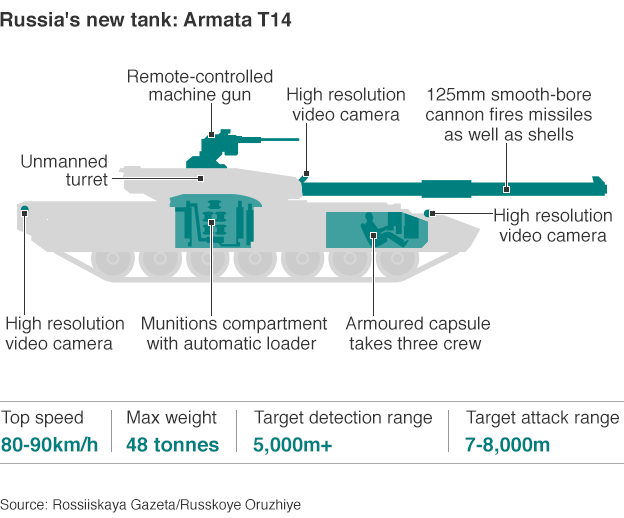

The Armata is a highly automated tank replacing much of Russia's Soviet-era armour

A Russian innovation in armoured warfare has pushed Norway to replace many of its current anti-tank systems.

Active protection systems (APS) are being built into Russia's new Armata T-14 tank, posing a problem for a whole generation of anti-armour weapons, not least the US-supplied Javelin guided missile, used by the Norwegian Army.

The warning comes from Brig Ben Barry of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) in London. He says this is a problem that most Nato countries have barely begun to grapple with.

APS threatens to make existing anti-tank weapons far less effective, and there is little real discussion of this among many Western militaries, he says.

Some countries are conducting research and trials to equip their own tanks with APS. "But they seem to miss the uncomfortable implications for their own anti-armour capabilities," he says.

Norway is one of the first Nato countries to grasp this nettle. Its latest defence procurement plan envisages spending 200-350m kroner (£18.5-32.5m; $24-42m) on replacing its Javelin missiles, "to maintain the capacity to fight against heavy armoured vehicles".

"There is a need for [an] anti-tank missile," it says, "that can penetrate APS systems".

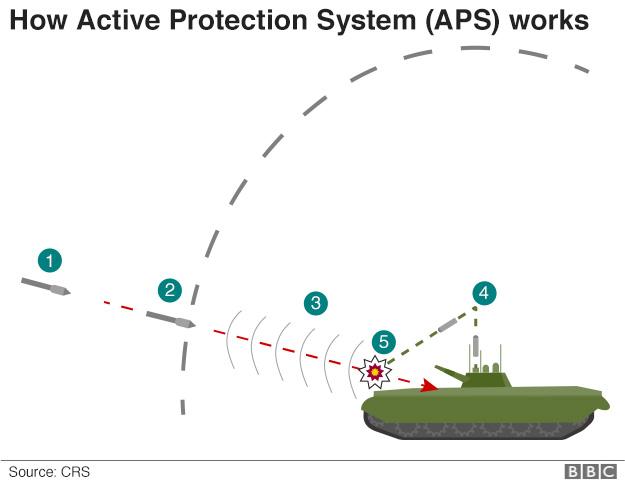

Enemy launches weapon at tank

Sensors detect incoming threat

Tracking radar calculates impact point

Active Protection System launches countermeasure

Countermeasure destroys target

APS is the latest twist in the age-old battle between offence and defence in military technology.

At different periods one side has held the advantage over the other. The armoured knight once ruled supreme, but the widespread use of firearms put paid to the armour-clad nobility's dominance.

Since World War Two the tank, like the knight of old, has reigned supreme on the battlefield.

It is of course vulnerable to the main guns of other tanks. If you have a heavy enough shell and a gun firing at high-enough velocity you can punch through even the best armour.

But tanks are also vulnerable to other weapons systems, and that is what APS is designed to deal with.

Anti-tank training in South Korea: Shoulder-launched missiles can destroy tanks

Since World War Two a whole category of lighter, man-portable anti-tank weapons has been devised.

Since they have to be carried by the infantry they depend not upon velocity and mass to get through the tank's armour, but on a chemical reaction. These warheads impact on the external armour and a metal core forms into a molten jet that pierces through.

Tank designers have tried to counter this in all sorts of ways, with reactive panels that explode outwards when hit; or by providing additional layers of spaced armour, to detonate the incoming round away from the tank itself.

APS takes a whole new approach. It is essentially an anti-missile system for tanks, with radars capable of tracking the incoming anti-tank missile, and projectiles that are launched to disrupt or destroy it.

Israeli Merkava tanks are equipped with the APS defence

Israel is among the leaders in this field and its Merkava tanks used it with some success during the last upsurge of fighting in Gaza.

The Israeli Trophy system is being evaluated by the Americans. Britain too is looking at such systems and the Dutch have recently decided to equip their infantry combat vehicles with another Israeli-developed system.

The fitting of APS to armoured vehicles is intended to counter a variety of weapons, ranging from the ubiquitous Russian/Chinese RPG (rocket-propelled grenade) to much more sophisticated guided anti-tank weapons like the Russian Kornet.

But Brig Barry at the IISS is pointing out that Russia's APS technology raises questions about many of Nato's anti-tank defences too. Norway is taking action - and he believes other Nato countries will have to do the same.

- Published2 March 2017

- Published6 May 2015