Reality Check: Have the Greek bailouts worked?

- Published

As eurozone finance ministers meet in Brussels for crucial talks on Greece, Reality Check looks at whether the bailouts the country has received have secured Greece's economic survival or just created unsustainable debt.

Neither Greece nor its creditors would say they are happy with how it has worked out.

In 2010, when the Greek debt crisis started, Greece received €110bn (£96bn) in bailout money.

And in 2012, the country received a second bailout of €130bn.

These loans, from the eurozone and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), were deemed necessary to stop Greece going bankrupt.

In exchange, Greece was required to make deep public spending cuts, raise taxes and introduce fundamental changes to the public sector and labour legislation.

In August 2015, the eurozone countries agreed to give Greece a third bailout, of up to €86bn, on the condition of further changes.

The next tranche of that bailout, which Greece needs in order to honour repayments due in July, is being discussed at the eurozone finance ministers' meeting on Thursday.

Grexit avoided

In 2010, they managed to keep Greece in the euro and prevented the collapse of the common currency.

So, from the perspective of the eurozone as a whole, a chaotic "Grexit" did not happen.

But seven years on, and many more billions of euros later, was this price worth paying, both from the point of view of Greece's creditors and of the Greek people?

It is impossible to know what the situation would be like now had Greece not received the bailouts, but the consequences of receiving them have been painful.

Half of under-25s unemployed

For the Greek people, the bailouts and the austerity measures implemented with them have come at a huge cost.

Unemployment remains staggeringly high: 22.5% of Greeks were unemployed, external in March 2017. And almost half of people under the age of 25 were out of work

Those who do work, earn less. The minimum monthly wage at the beginning of the crisis was €863. It has now fallen to €684

Pensioners have been hit particularly hard. Pension changes since 2010 mean 43% of pensioners, external now live on less than €660 a month, according to the Greek government

Government spending on health, external was almost halved between 2010 and 2015, while the education budget, external was cut by 20%

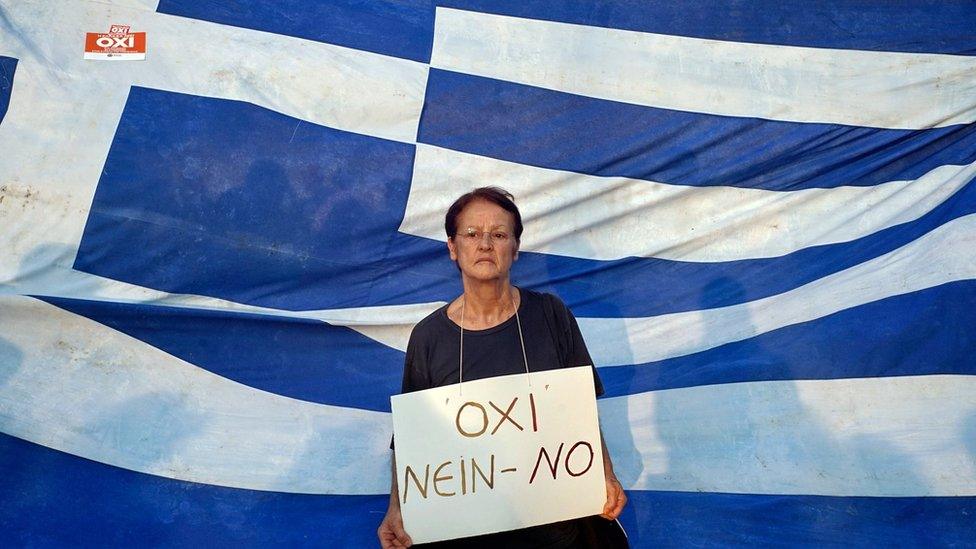

Woman protests at anti-austerity demonstration in 2015

First budget surplus

Greece's creditors, strongly influenced by Germany, demanded that Greece start spending less than it earned.

In 2016, for the first time, Greece achieved this. The surplus is small, at €1.3bn or 0.7% of GDP.

But this can hardly be seen as a success - the economy has shrunk and the overall debt pile is still going up, not down.

What to do about the debt is the main stumbling block between Greece's creditors, the eurozone countries and the IMF.

Some countries, including Germany and the Netherlands, do not want to release any more money unless the IMF agrees to be part of the third rescue programme for Greece.

They think that, without the IMF, the EU institutions would be too soft on Greece in their demands for changes.

The IMF has so far refused to get involved because it says Greece's debts are unsustainable and need restructuring.

It says that Greece cannot be expected to grow out of its debt problem, even with the full implementation of changes.

Crucial talks

The talks on Thursday will determine whether Greece will be able to make the repayments due in July.

But the key question is whether the creditors can reach any agreement on restructuring Greek debt.

French President Emmanuel Macron said he would "lead the fight" for debt relief because "there's no chance of returning to a stable economy and society in the eurozone with the current level of debt".

Germany is much more reluctant to allow any debt relief, ahead of elections there in September.

Bailouts for Greece may have dropped from the headlines, but have they worked? Not yet.

- Published23 May 2017

- Published18 May 2017