Germany's big businesses' Brexit worries

- Published

It must be serious. They've deployed the Royals.

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge have been on tour in Germany with a very specific purpose: to reassure the country that Brexit doesn't mean the break-up of a beautiful relationship.

Prince William, after speaking a few words in German, told guests at a British embassy garden party: "This relationship between UK and Germany really matters, it will continue despite Britain's recent decision to leave the European Union. I am confident we will remain the firmest of friends."

But since the British election, German politicians are more troubled than ever about Brexit. The German council for foreign relations' director, Daniela Schwarzer, told me: "Policymakers in Berlin are surprised and worried at the degree of confusion in London, the lack of clarity as to the strategy the UK wants to follow.

"There is a lot surprise about how the negotiations are being handled and the somewhat incoherent messages which come out of London."

Of course, Germany is just one country in the European Union - but it is first among equals, its chancellor by far the most senior politician, with a new and determined ally in President Macron, who's refreshed the Franco-German alliance.

Even before Brexit became a reality, there's been an argument, almost an assumption, that German industry would put pressure on German politicians to argue for a good deal for the UK - access to the European market without having to abide by the rules.

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge recently toured Germany

So far, Mrs Merkel has been adamant: no cherry picking. Will German industry push her to change her mind?

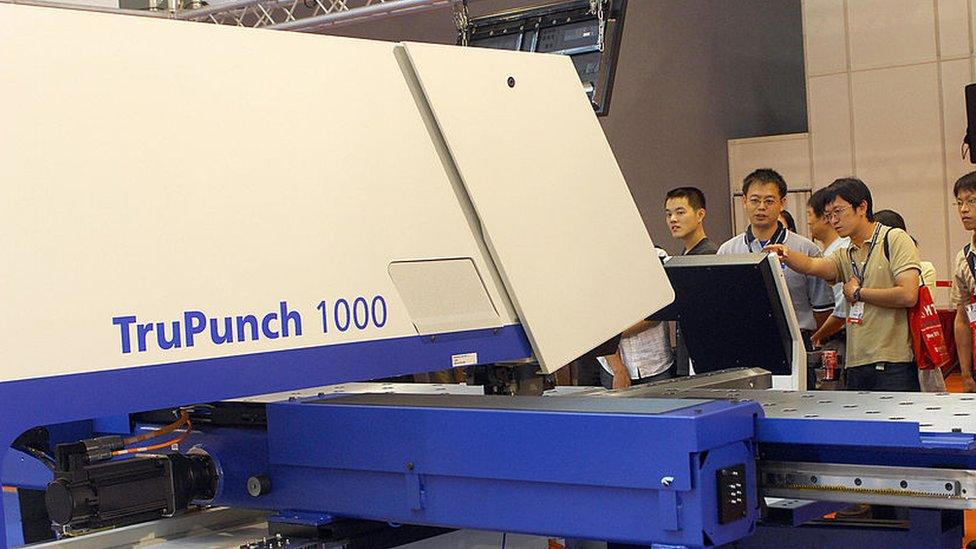

I visited the Trumpf company in Stuttgart, a concern with a turnover of 3bn euros (£2.7bn) a year that makes sheet metal, laser cutters and machine tools. It employs 4,000 people in Germany and another 8,000 globally: in the USA, China, Japan, South Korea - and in Luton, Southampton and Rugby.

The company's Heidi Maier tells me orders from the UK are up because people have got used to the idea of Brexit.

"Despite political insecurities and decisions we don't like and we don't back, our business is doing very well," she says.

We stand in front of the True Punch 5000. The machine is swift and certain, precise and elegant, all the qualities that make Germans so proud of their engineering prowess.

The exact opposite of these qualities - slowness and uncertainty - is what worries German industry about Brexit.

I ask Ms Maier what they want Mrs Merkel to push for. "What would help is decisions, and fast decisions," she says.

"As soon as we know the new rules, we can go ahead. We are actually preparing for tariffs, which is the implication [of what the British government is saying], which would worsen our business. The goods we produce in Great Britain would become more expensive due to the tariffs, and we don't know how our customers would react to that."

Most German businesses tend to lobby government through powerful trade associations. And one industry has more horsepower than any other.

Germany's glittering car industry is an industrial giant with immense political clout and a 400bn euro turnover, employing 800,000 people. And the relationship with the UK is very important. One in seven cars exported from Germany goes to the UK, its single biggest market.

The Trumpf machine is just one example of German high-tech engineering

Ever since Brexit was a speck on the horizon, enthusiasts for leaving have argued the mighty German auto industry wouldn't allow politicians to punish Britain, a point I put to Matthias Wissman, the president of the VDA, the German automotive industry association.

"What we want is to keep the European Union of the 27 together," he says. "That is the first priority. Second priority is to have a trade area with the UK with no tariff barriers, no non-tariff barriers. That is possible if the UK understands what the preconditions are.

"We want a good deal for Britain, but the best deal for Britain would be to stay in the customs union. Anything else would be worse for both sides. The best thing would be to stay in the internal market, like Norway."

He accused pro-Brexiteers of making "totally unrealistic" promises. "I see a lot which is astonishing for a friend of Great Britain. I miss the traditional British pragmatism. We would like to have it in the future, but I see more and more ideological points of view which make pragmatism very difficult and unfortunately in both parties, Conservative and Labour."

The UK is the German auto industry's biggest export market

When I put to him Liam Fox's view that a trade deal with the EU could be "one of the easiest in human history", he laughs and says it would take years and years but "time is running out".

"You need a transition period. And if you want an easy solution, stay in the customs union and the internal market.

"A transition period would also be very pragmatic. We hope that on the British side that gets deeper and deeper into the intellectual capabilities of those who decide."

This is not just the view of one man, or one industry. There seems to be a consensus among the industrial powerbrokers.

Klaus Deutsch of the federation of German industry, the BDI, makes it clear they did not want Brexit in the first place and would like the UK to stay in the single market and observe all the rules.

But that's not the government's intention, so what follows?

"We would favour a comprehensive agreement. But the most important thing is legal certainty in the period from A to B. If you don't have a transition period of many years, then there will be a huge disruption to all sorts of businesses.

"The concern of business is unless you get a clear cut and legally safe agreement, you can't sell pharmaceuticals, or cars or what have you, across the Channel, you have to stop business, divest, change business models."

Will Germany prioritise EU unity over its economic relationship with the UK?

He makes it clear only the British government can decide what it wants, but what about the idea they'll push Mrs Merkel to soften her approach?

"That's completely unlikely," Mr Deutsch says. "The importance of the European Union for German corporates is even higher than the importance of a bilateral relationship with the United Kingdom. So, the priority of safeguarding… the unity of the European Union is much more important than one economic relationship. There are a lot of illusions - it won't happen."

Speaking on BBC Radio 4's The World This Weekend programme, Owen Paterson, the former cabinet minister, who recently visited Germany, told me he had felt a "sense of denial" in the country over Brexit.

"It is hugely in everyone's interest that we maintain reciprocal free trade and as we have absolute conformity of standards, everyone should get their head round that," he told me.

"Whereas [the Germans] are still thinking entirely in terms of remaining in the current institutions and that's clearly what we are not going to do.

"We're not going to stay in the single market. We are not going to stay in the customs union. We're certainly not going to stay under the remit of the European Court of Justice. I found that that was something they had not really got their heads round."

And my overriding impression of the view of the big beasts of Germany industry?

Frustration that they don't know where the British government wants to head and a strong sense that any outcome will be worse than what exists.

But also, a total rejection of the idea that the economic relationship with the UK outweighs the German interest in European unity.

- Published17 January 2017

- Published29 March 2017