Are migrants paying price as EU targets smugglers in the Med?

- Published

The UNHCR calls for $420m to stop people risking their lives crossing the Mediterranean

There was a serene, enchanting glow to the view from the Vos Prudence search-and-rescue ship as it slowed to a standstill off the Libyan coast a few hours after sunset.

Three bright orange flames from an oil-rig were visible on the horizon. Closer to the ship, a seagull appeared over a moonlit strip of sea, flying so low it almost brushed against the waves.

We were on a ship run by the charity Médecins Sans Frontières on a mission to rescue migrants in distress at sea.

Days and nights passed with nothing in view but the open sea, until suddenly, out of the blue, the people start coming.

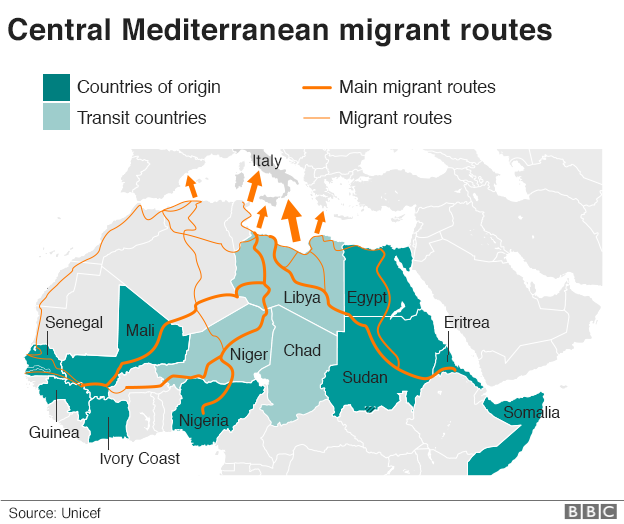

They are pushed out to sea from the Libyan coast, on unseaworthy boats packed with as many people as they could carry. They come from across North and sub-Saharan Africa, the Horn of Africa, Bangladesh, and Syria.

How EU tries to stop the smugglers

The EU wants to seal off the Central Mediterranean migration route, much as it did with the Aegean route between Turkey and Greece last year.

The EU strategy rests on two pillars. In Libya, it is funding and training the Libyan coastguard to stop the migrants before they cross into international waters, and send them back to Libya.

The migrants come from a number of countries including Nigeria, Guinea and Ivory Coast

Outside Libyan waters, it has deployed military vessels to disrupt the smugglers' business, mainly by burning their boats so they cannot be reused.

But increasingly the strategy has come in for criticism.

Successive reports have suggested a link between the burning of the boats and the rising death rate on the Central Mediterranean. As the smugglers adapted by using cheaper boats that were more unseaworthy, the crossing became more dangerous for the migrants.

And testimony from the migrants themselves suggests the Libyan coast guard could be playing a double game: taking money from the EU to intercept migrants, and money from smugglers to let them pass.

A few hours after we arrive in the search and rescue (SAR) zone, the Italian Navy's Maritime Rescue and Co-ordination Centre in Rome calls with news that several boats have set off from Libya.

By the time we arrive, the action has already started.

When the EU focused on burning boats, the smugglers began using more dangerous dinghies

From one side of the deck, there is a plume of thick smoke polluting the clear blue horizon; a smugglers' boat set on fire by an Irish military vessel following a rescue operation.

On the other side of the deck, much closer to the ship, an empty wooden boat is being towed away by two men on another boat, presumably to Libya for reuse.

Men believed to be migrant smugglers are spotted during a rescue effort in the Mediterranean

Since late 2015, the EU has stepped up the destruction of migrant boats after the rescues, aiming to disrupt the business model of smugglers.

But there are indications that it is the migrants, not the smugglers, who are paying the price.

Smugglers have shifted from using wooden boats to cheaper dinghies

The EU's own data has shown that the smugglers quickly adapted by using more rubber boats, as the costlier wooden boats became a "less economic" option.

And as the EU stepped up its efforts, the death rate was rising.

A string of reports, including by Amnesty International and the UK House of Lords, external, began drawing links between the anti-smuggling operation, the smugglers' deteriorating offer for migrants, and a steadily rising death rate at sea.

Soon enough, the lower deck of the Vos Prudence becomes packed with people - 727 men, 53 children, and 97 women - and heads for the Sicilian port of Palermo.

Crammed uncomfortably on the lower deck with barely enough space to stretch, they begin to describe the medieval horrors accompanying Libya's descent into lawlessness.

The lower deck of the MSF becomes filled with the migrant arrivals

Time and again on board the Vos Prudence, we heard of torture in underground prisons, kidnapping for ransom, slavery, and killings on a whim.

What is the role of Libya's coast guard?

For many, being forced back to Libya is the worst thing that could happen to them. They give a confusing picture of the coast guard.

Abdullah, a Sudanese from Khartoum, told me a friend of his, also from Sudan, got on a boat that was intercepted by the Libyan coastguard and forced back to Libya. He was sold into forced labour on a farm, until he managed to leave again.

After rescuing migrants from the sea, the Vos Prudence will take them to port in Italy

But Abu Yasser, from the Syrian city of Aleppo, said the coast guard escorted the boat he was on all the way into international waters, then directed it towards an NGO vessel, and away from a military one.

"The real smugglers," he told me, "are the Libyan coast guard."

Husam, from Libya, said smugglers who pay get past. "There's no coast guard. It's all militias."

But Italy and the EU appear more focused on the search-and-rescue charities than the Libyan coast guard.

Why Italy wants to board NGO ships

The Italian government has drafted a code of conduct and has warned NGOs that if they fail to sign it they will be shut out of Italian ports.

One of its demands is for charities to co-operate more actively with the anti-smuggling operation, by collecting when possible "the makeshift boats and the outboard engines used" by smugglers, and notifying Frontex, the EU's border and coast guard agency.

Italy wants its authorities to have the right to board NGO ships

Another of the 12 points of the code is for NGOs to increase co-operation with Italian police, allowing them on board upon request to "conduct preliminary inquiries and investigations".

Both Frontex and MSF have become increasingly aware that the Central Mediterranean route is being used for trafficking in Nigerian girls and women.

"It is of utmost importance to protect them, to identify them early, to separate them from their traffickers before they disappear in the world of abuse," Frontex told the BBC in an email, before the code of conduct was delivered to the charities. "We can do it only if all actors actively cooperate with the police."

Stefan van Diest of MSF told us it was "not MSF's role to police international waters or to investigate trafficking and smuggling networks".

"We are doctors, not police and we are present on the Mediterranean to save lives."

NGOs fear that Italy's code of conduct is aimed at limiting the number of people rescued at sea

But Mr Van Diest added that MSF was "acutely aware of the use of this route by traffickers".

"Potential victims of trafficking are systematically referred to the authorities and appropriate protection agencies during disembarkation."

The code of conduct will make these differences more pressing to resolve. MSF must now consider whether and to what extent to change the way it operates at sea.

For now, though, the work continues.

After filling up with fuel on the island of Malta, the ship heads back into the search and rescue zone.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published19 July 2017