Barcelona attacks: Spain's long anti-terror experience

- Published

Las Ramblas, Barcelona: Police on duty as Spain is left shaken

Spain was already on high alert for a possible attack when a van smashed into the crowd on Barcelona's famous Las Ramblas boulevard, killing 13 people.

Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy called it a "jihadist attack". It is believed an Islamist cell of at least eight militants was involved.

In June 2015, Spain raised its terror alert level to four - one short of the maximum, level five. And since June 2016, Spanish security sources say, police have detained 164 suspected jihadists.

The use of a van zig-zagging at high speed through a pedestrian zone recalls the jihadist attacks in London, Berlin and Nice.

In December, Spain's interior ministry recommended installing barriers to stop any vehicle being driven into Las Ramblas, but the city did not do so, the ABC daily reports.

The Barcelona attack was claimed by so-called Islamic State (IS), though nothing confirms a direct IS link to it yet.

Five suspected jihadists were shot dead by police on Thursday night in Cambrils, a town 120km (75 miles) south of Barcelona.

Suspects killed in second Spain attack

Spain attacks - latest updates

Spain attacks: What we know so far

In pictures: Barcelona van attack

In recent years Spain has intensified its security co-operation with nearby Morocco. There is believed to be a Moroccan connection in the Barcelona case.

The van driver is still on the run, but police have arrested four suspects - three Moroccans and a Spaniard from the North African enclave of Melilla.

One of the Moroccans was named as 28-year-old Driss Oukabir. The hunt is on for his brother Moussa, thought to have rented the van using Driss's name.

Bombers blew up Madrid commuter trains in 2004

Home-grown jihadists

Barcelona has just seen Spain's worst attack since the Madrid train bombings of March 2004, in which 191 people died and more than 1,800 were injured.

Islamist militants detonated 10 bombs on four commuter trains in the capital, in what remains Europe's bloodiest terror attack this century.

Spain has long been a potential target because hundreds of its soldiers are in the international coalition against IS. They are training Iraqi security forces but do not have a combat role.

In recent years Spain has seen a home-grown problem of Islamist radicalisation, said political violence expert Javier Argomaniz of St Andrews University.

Since 2013 about half of the suspects arrested have been Spanish-born, mostly very young, from poor, marginalised immigrant families, he told the BBC.

"There is radicalisation both online and through peer groups, but the online element is very strong," he said.

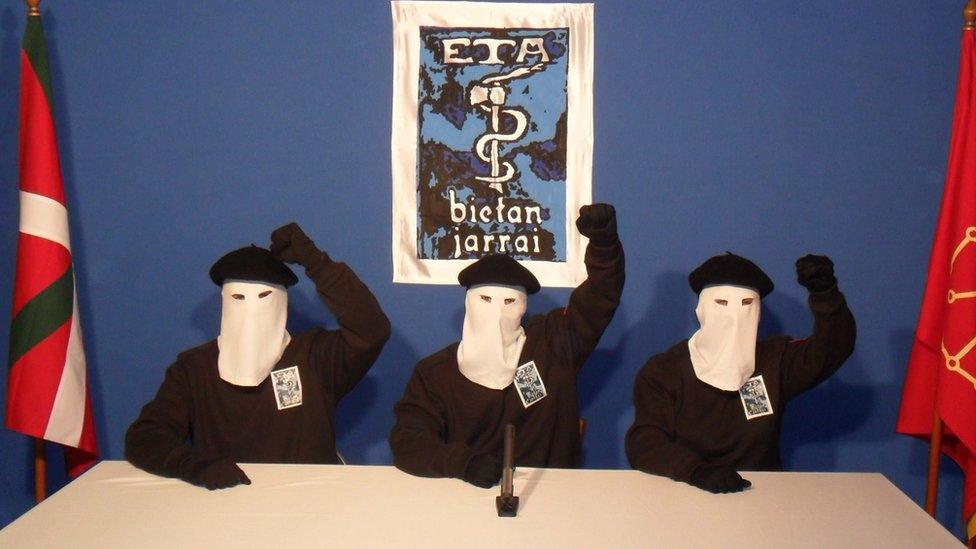

Lessons from Eta war

The violent Basque independence campaign waged by Eta for decades led Spain to pour resources into anti-terrorism units. The lack of major terror attacks in Spain since 2004 may be evidence of their professionalism.

Eta was the focus of Spanish anti-terror efforts before the jihadist threat grew internationally

The last terror attack in Barcelona was the murder of a policeman by Eta militants in 2000.

Facing up to the Eta threat saw Spanish anti-terror expertise shared with the French police, who played a key role in sapping the group's capability.

Eta is now disarming. The last Eta attack on Spanish soil was in Majorca in 2009, when a car bomb killed two Civil Guard officers.

Islamist radicalisation has been concentrated in four areas of Spain in recent years, the Spanish daily El Pais reports. Barcelona - with a large Muslim community - is the main area where it has happened.

The others are: Melilla, Ceuta (Spain's other North African enclave), and Madrid and its suburbs.

As part of its anti-terror measures, Spain brought in new laws against funding of terrorism, self-radicalisation through social media and travel abroad to train or fight with a jihadist group. All those crimes carry prison sentences.

Most of the 178 Spanish citizens who have gone to fight for IS or other jihadist groups have been from Ceuta or Melilla. About 10 times more jihadists have gone to the Middle East from France, it is believed.

- Published17 August 2017

- Published27 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017