Bosnia's war-ravaged Olympic track comes back to life

- Published

Take a ride down the track with some of the team rebuilding it

A summer luge may look like a plastic tray on wheels. But at full speed it hurtles around the concrete banking of Sarajevo's Olympic bobsleigh track with the roar of a Star Wars TIE fighter swooping in for the kill.

There are no barriers to prevent encroachment on the track, but standing clear is essential. Flat out, the flimsy vehicle careers down the course at almost 140km/h (87mph).

There is an undeniable irony about a Winter Olympic luge track that comes to life in the summer but has to close when the temperatures drop. A cursory inspection of the course reveals why high-speed action on ice is currently impossible.

The structure of the luge track has seen better days, but the site at Mount Trebevic is still a draw for visitors

The lighting stanchions that once illuminated night-time racing are twisted and denuded of their bulbs; the track's refrigeration pipes have been ripped out; and, at the top of the course, the start houses are in ruins.

All a legacy of the ruinous conflict in the 1990s, when Mount Trebevic became a strategic asset for Bosnian Serb forces.

"During the war, this was the frontline," says Senad Omamovic, the president of the Bosnian Luge Federation and the driving force behind the unlikely revival of the track.

Part of the track lies in ruins, cordoned off from lugers keen to practise

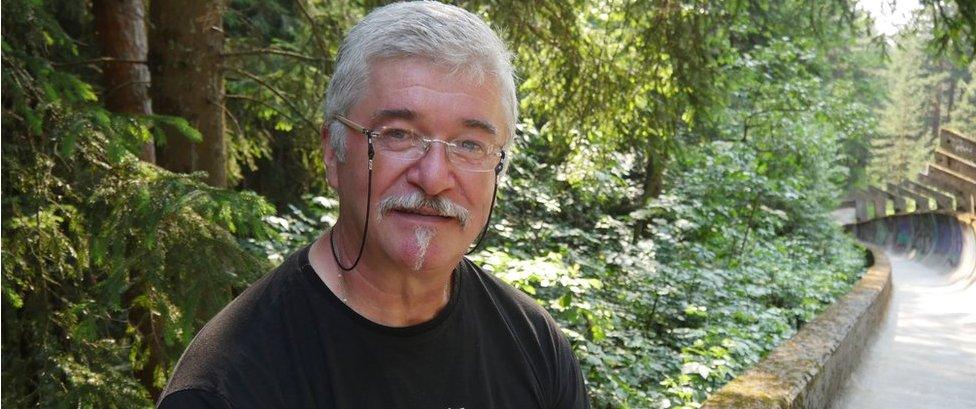

Senad Omamovic is trying to restore Bosnia's luge track to its former glory

Senad watched the 1984 Games as a frustrated spectator, then became an international luger for the rest of the decade. The war of the 1990s brought his sporting career to a shuddering halt - and left his home track shattered. But still he insists there is no course that can compare with Sarajevo.

"For me, for sure, this is the best track in the world. Before the war we had three World Cup races here every year, in bob, luge and skeleton. Many athletes and colleagues from other countries say it's really nice - safe, technical and fast. Really, really fast."

Now he is working to bring fast times back to Sarajevo. Sporting a t-shirt with the slogan "Sarajevo is still alive", Senad pitches in with the repair work on the track. The lower half of the course is now fit for use in the summer - and attracting a new generation of Bosnian lugers.

Mirza Nikolaev (R) and his team-mate Hamza have spent the summer practising on the old track

16-year-old Mirza Nikolaev asked his parents to take him to the track after catching an item on the local TV news programme. He quickly established himself as a member of Bosnia's junior luge team.

"I fell in love with the sport instantly. Senad introduced me to it and I loved it. I wanted to do it a hundred times a day," he says.

For Mirza and his team-mates, practice on the Sarajevo track makes winter competition around Europe possible.

"If I hadn't practised here, it would have been a disaster on ice," he says. "It helps a lot that we have our own track; only nine countries have one."

Speed there may be, but glamour is in short supply. The tattered skinsuits that Mirza and his team-mate Hamza use betray both the dangers of the sport - and the lack of funding. And if they want to keep practising, they have to get their hands dirty.

Hamza is also on Bosnia's junior luge team

"We help to rebuild the track," says Mirza. "Every year we come after the winter is over and everything has gone rotten, everything has cracked after the snow and rain. Every single thing that we previously fixed is broken again. So we have to keep fixing it every year."

Even in its reduced state, the track is quite spectacular. Multi-coloured graffiti covers its banks as they sweep down the forested slopes of Mount Trebevic. Thrill-seeking mountain-bikers record their runs on helmet-mounted cameras, and foreign tourists come to gawp as if they were exploring a Cambodian temple half-consumed by jungle.

Local guides make a decent living from bringing guests up Trebevic and allowing them to amble on to the unrestored top half of the course.

The site needs constant attention and much of the structure needs replacing

"Where else in the world can you come and walk down a bobsleigh track?" asks Asim, as he directs a small group of young tourists towards the concrete. But despite the income to be made, he would prefer to see the track restored to its former glory - with winter racing.

"I would jump out of joy to see this going again. How many cities in Europe boast a bobsleigh track and can train their people there? You could rent this; other people would come here - the city could earn money from this."

Senad shares this vision and believes he is winning the battle to bring the Sarajevo track back to Olympic standard.

"Lots of people from outside want to invest to rebuild the track," he says. "Now many countries come here for training - Slovakia, Poland, Slovenia. And this year they want to come from Sweden and Norway. This is great for us."

Sarajevo is hosting the next Winter European Youth Olympic Festival in 2019 - 35 years on from its moment in the international sporting spotlight. Restoring the track in time might seem an impossible dream, but Bosnia's young lugers believe it can be done.

- Published18 March 2017