Catalan referendum: Spain battling to halt the vote

- Published

Catalonia's police force has been caught up in the power struggle over Sunday's vote

"It won't happen," insists Spain's prime minister, and for the Catalan leaders trying to organise Sunday's vote on seceding from Spain, his words are becoming harder and harder to contradict.

The nerve centre of the 1 October referendum - Catalonia's economy department - has been seriously damaged by raids carried out by Spain's military police force, the Civil Guard.

Fourteen junior officials and associates were arrested, but more importantly close to 10 million ballot papers were impounded, and websites informing Catalans about the election have been shut down.

The government in this north-eastern region of Spain admits its logistical effort to organise the referendum has been seriously disabled, as it defies a suspension of the vote by Spain's constitutional court.

Catalan police, like these on the left, have been ordered to accept the command of Spain's Civil Guard (R)

Police at heart of struggle

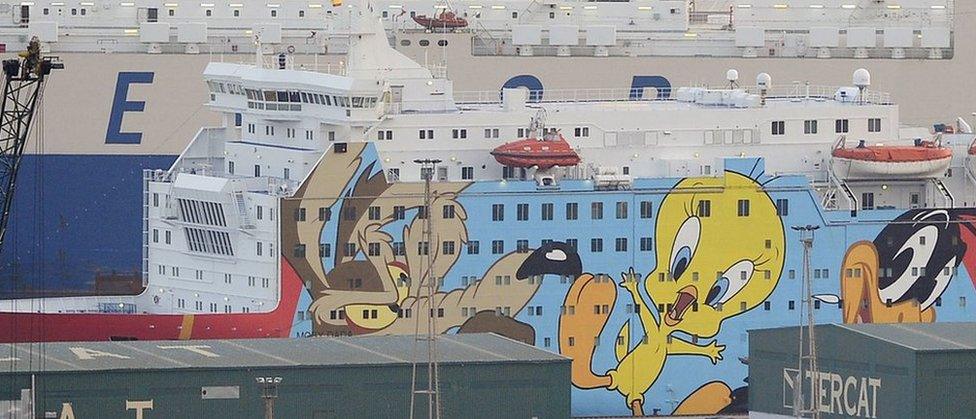

Spain's interior ministry has hired three ferries to accommodate the extra security contingent being sent to the region, and a power struggle has blown up over control of Catalonia's regional police, the Mossos d'Esquadra.

Catalonia's chief prosecutor has ordered the Mossos to accept the command of Spain's Civil Guard to co-ordinate efforts to gather evidence of plans to hold an illegal referendum, and in effect stop it happening.

But the head of the Catalan force, Major Josep Lluís Trapero, is refusing to accept that order.

And Catalan President Carles Puigdemont has spoken out against "practices worthy of a totalitarian state" as Spain tries to smash the planned ballot.

This ship, decorated bizarrely with cartoon character Tweetie Pie, is one of three chartered to house extra Spanish police

Will the vote happen?

Mr Puigdemont insists it will. And after millions of ballot papers were seized, activists took photocopiers into the streets over the weekend to print off new ones.

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has appealed to the Catalan government in an official address "not to go ahead" with the vote. "(This) illegal plan of rupture has no place in a democratic state under the rule of law such as ours," he said.

Why some Catalans want independence

However, the BBC has learned from a senior minister in the Spanish cabinet that the government still expects "a watered-down ballot" to take place. The government is worried about the possibility of violence if supporters of the referendum resist police efforts to block polling stations.

What if Spain cannot stop it?

Beyond measures already taken by the courts, Spain's authorities still have further heavy weapons in their legal armoury if Mr Puigdemont and his associates refuse to back down.

Spain's government-appointed chief public prosecutor, José Manuel Maza, suggested on Monday that the Catalan leader could be arrested and charged with civil disobedience, abuse of office and misuse of public funds.

Pro-independence marches so far have been peaceful but there were scuffles with police last week

An article in Spain's constitution allows the government to ask the Senate for permission to use "the necessary means" to ensure that any of Spain's 17 autonomous regions such as Catalonia comply with national law.

The vague phrasing of Article 155 and the fact that it has never been invoked mean it could allow the government to shut down Catalonia's government and even the region's parliament should Mr Puigdemont choose to follow through and announce independence in the event of a Yes vote on Sunday.

If there is a vote and a yes tor independence, Mr Puigdemont has said that the first thing he would do on Monday is "call for dialogue with the Spanish state and the European Union", although he insists his roadmap to full sovereignty will go ahead regardless.

The Catalan vote is turning into a battle of wills between Mariano Rajoy and Carles Puigdemont

Unofficially, Catalan government sources admit a low turnout of less than 50% of the region's 5.5 million voters will force them to reconsider the situation.

Mr Puigdemont and other Catalan government members have said they will ignore court rulings suspending them from office.

From 2 October there could be a troubling situation in which two distinct legal realities coexist in Catalonia, with Spain declaring the region's government defunct while lawmakers bunker down in the Catalan parliament in Barcelona to vote for secession.

What does rest of Spain think?

Left-wingers from parties such as Podemos and nationalists from other regions like the Basque Country are pressing for a reform package that puts the option of a legal referendum on the table.

But Spain's two largest parties - Mr Rajoy's Popular Party and the Socialist PSOE - do not agree with regions being able to hold a legal referendum on independence from Spain.

Anti-Catalan sentiment among Spaniards may also be on the rise. Crowds have given a send-off to police contingents travelling to Catalonia with cheers of "Go, get them!"

Is there any way out?

For the first time since becoming Spanish prime minister in 2011, Mr Rajoy has recently agreed to revise Spain's system of regional government, opening the door to possible constitutional reforms. Congress has agreed to form a standing committee charged with considering reform initiatives.

Tinkering with Catalonia's autonomy statute with no chance of a legal exit from Spain would be a hard sell for regional politicians from the nationalist coalition currently in power. The pro-independence movement has demonstrated its strength in recent years with massive marches in Barcelona.

But Catalans against independence want a say, too. "We non-nationalists won't accept a reform that just gives us more finance and powers; we want a diverse and plural Catalonia with greater freedoms for Spanish speakers," said Ana Losada, a member of Societat Civil Catalana, which opposes Sunday's referendum.

- Published15 September 2017