The fateful life of history's most famous female spy

- Published

On the morning of 15 October 1917 a grey military vehicle left the Saint-Lazare prison in central Paris. On board, accompanied by two nuns and her lawyer, was a 41-year-old Dutch woman in a long coat and a wide, felt hat.

A decade earlier this woman had the capitals of Europe at her feet. She was a legendary 'femme fatale' known for her exotic dancing, and her lovers included ministers, industrialists and generals.

But then came the war, and the world changed. She thought she could keep charming her way around Europe. But now the men in top hats wanted something more than sex. They wanted information.

And that meant spying.

This was Mata Hari, and she was about to be put to death.

Her crime? Being an agent in German pay, gleaning secrets from Allied officers who she slept with, and passing them on to her paymaster, leading to lurid newspaper claims about her being responsible for sending thousands of Allied soldiers to their deaths.

But the evidence presented at her trial, plus other documents, cast a different light: that she was actually a double agent and may have died as a scapegoat.

Now, exactly a hundred years on, new light has been shed on the most famous woman spy of all time with the release of hitherto unseen documents by the French defence ministry.

These include transcripts of her interrogation by the French counter-espionage service in 1917. Some are also on display at a new exhibition at the Fries Museum in her hometown, external of Leeuwarden in the Netherlands.

Mata Hari facing the firing squad. There is doubt over this picture and it may be a still from a contemporaneous film

Among the papers is the telegram to Berlin from the German military attaché in Madrid which led to Mata Hari's arrest at a hotel on the Champs-Elysees, and later served as a key piece of evidence at her brief trial.

Born Margarethe Zelle in 1876, Mata Hari (the name is said to come from the Indonesian for 'eye of the day' - the sun) had an extraordinary and tragic life. After a miserable marriage in the Dutch East Indies she reinvented herself as the louche diva of 'Belle Epoque' Paris, where her sensual dances were a ticket to the inner courts of European society.

"Even without the spying, Mata Hari would be remembered today because of what she did in the capitals of Europe in the early part of the last century," says Hans Groeneweg, curator of the Fries Museum.

"She more or less invented the striptease as a form of dance. We have her scrapbooks on display at the exhibition, and there are piles and piles of newspaper clippings and photographs. She was a celebrity socialite."

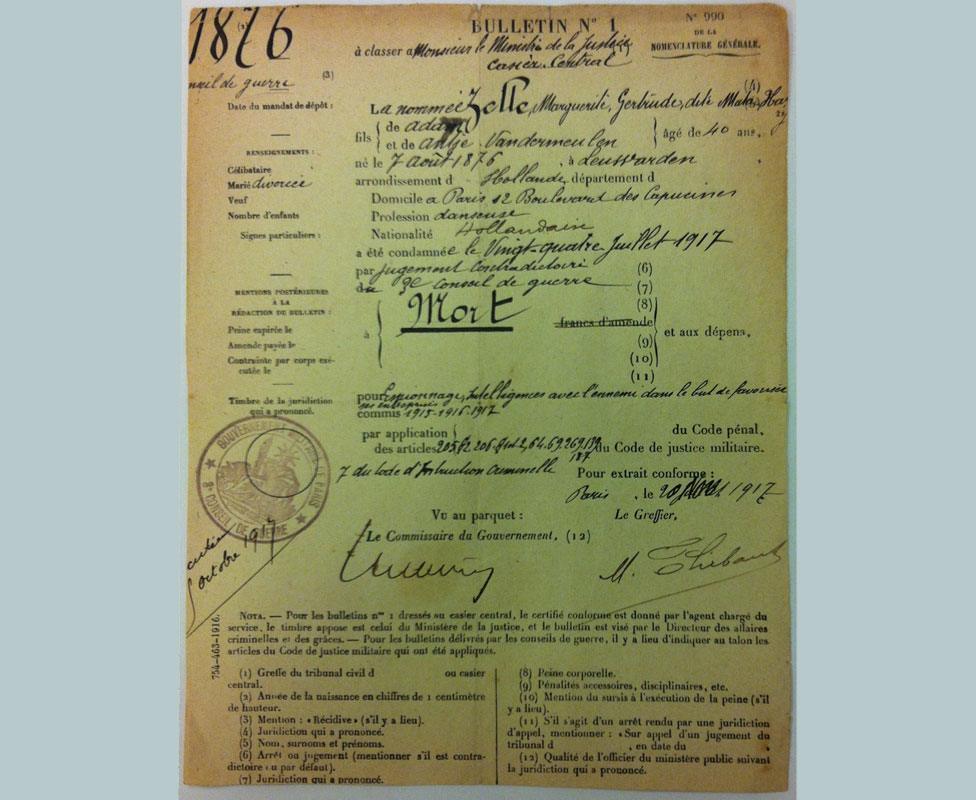

The French court's notification of Mata Hari's death sentence

Sadly though, the Mata Hari myth is dominated by the espionage. Over the years many historians have come to her defence. She was sacrificed - some say - because the French needed to find a spy to explain their succession of reverses in the war.

For feminists, she was the perfect scapegoat because "loose" morals made it easier to tar her as an enemy of France.

Until now the full details of her interrogation by prosecutor Pierre Bouchardon (incidentally the man who later prosecuted Marshal Petain) has been off-limits to historians.

It was known, though, that in 1916 - after a brief sojourn in London where she was interrogated by the British security service, MI5, external - Mata Hari returned to France via Spain.

In Madrid she made the acquaintance of Arnold von Kalle, the German military attaché. Her later story was that this was all in pursuance of her prior arrangement with French intelligence, under which she undertook to use her pre-war web of German contacts to help the Allied effort.

But it was von Kalle's subsequent telegram that led to her undoing. In it he set out to his masters in Berlin the details of a certain Agent H21. It gave addresses, bank details, and even the name of Mata Hari's faithful maid. There could be no question to anyone reading it that Mata Hari was agent H21.

The telegram, intercepted by French intelligence, is now available for scrutiny at the Leeuwarden exhibition. Or rather, the official translation of the telegram is available. Because therein lies the rub.

According to some historians, the whole telegram episode is fishy.

Police photo of Mata Hari from the day of her arrest

The French - it is argued - had long since cracked the code in which the telegram was written. The Germans knew the French had cracked it. And yet still von Kalle sent the message. In other words, he wanted the French to read it.

So, in this theory, it was the Germans who led the French by the nose into arresting and executing their own agent.

Or there is the other theory.

Why is there only a translation in the archives? Where is the original telegram? Could it be that the French themselves invented the document in order to pin the blame on Mata Hari? That way they would find their "spy". And the public would be satisfied.

Both theories make Mata Hari into a victim. One side or the other found it convenient to get rid of her, and so they did.

But the French archives throw up another detail, which actually relegates these hypotheses to the junior division. Because what the transcripts also show is that in June 1917, during her umpteenth interrogation, Margarethe Zelle decided to come clean: she confessed.

She told Bouchardon that yes, she had been recruited by the Germans. It was back in 1915 in The Hague.

Mata Hari's brooch is just one artefact in the Fries museum's exhibition

Caught outside France at the start of the war, she was desperate to get back to Paris. Karl Kroemer, German consul in Amsterdam, offered her the means… if she would be so good as to help them with certain information from time to time. Thus was created Agent H21.

Mata Hari insisted to her interrogators that she just meant to take the money and run. She said her loyalty was to the Allies, as she had shown when she subsequently promised to help French intelligence. But the evidence against her was now clear.

Arriving at the Chateau de Vincennes on the eastern outskirts of Paris, Mata Hari was led to a piece of ground where a post had been erected in front of an earthen bank. Twelve soldiers formed the firing squad.

Some reports say she refused to be blindfolded. As one hand was being tied to the post, with the other she made a brief wave to her lawyer. The commander lowered his sword in a swift motion, there was the sound of rifle fire, and Mata Hari crumpled to her knees.

An officer approached with a revolver and shot her once through the head.

After the execution, no-one came to claim Mata Hari's body. So it was delivered to the school of medicine in Paris where it was used for lessons in dissection. Her head was preserved at the Museum of Anatomy. But during an inventory some 20 years ago, it was found to have disappeared.

Presumed stolen.