Kurz and charisma: What propels young leaders to power?

- Published

"Black is Cool": Sebastian Kurz (sitting, centre) in a campaign photo in 2011

In Austria they call him "Wunderwuzzi" - meaning "whizzkid" or "hotshot".

At just 31, the conservative Sebastian Kurz is poised to become Europe's youngest leader, after giving the Austrian People's Party a dramatic makeover.

No detail is too small for the ambitious young politician eyeing the summit of political power.

In 2011 Mr Kurz posed on a jeep for a "Black is Cool" party campaign - when black was the party colour. But for this election, in which he emerged the clear winner, he made the party turquoise, in a big rebranding exercise.

The spotlight was on Sebastian Kurz in Austria's general election

The new colour obviously worked. But what else has propelled charismatic young politicians into power in recent years?

Vaulting ambition

Mr Kurz is the latest youngster to take his country's political establishment by storm and shake it up.

France elected President Emmanuel Macron, just 39, who revolutionised politics by launching a new liberal party, La République En Marche! (LREM). Just weeks after his presidential election triumph came LREM's clear victory in parliamentary elections.

He is France's youngest head of state since Napoleon.

In 2014 Italy got its youngest ever prime minister - Matteo Renzi, then aged 39 too. Like Mr Macron, he had never served in parliament, and was a novice in national politics.

President Macron (R) spotted a good photo op with Canada's youthful PM Trudeau at a G7 summit

But little Estonia upstaged even those "Wunderkind" examples. The vaulting political ambition of Taavi Roivas made him prime minister in 2014-2016, and he is still only 38.

Their success proves that voters are looking for much more than experience when they elect politicians. Youth and charisma clearly count for a lot, along with persuasive campaign rhetoric.

Some fear that in this digital age, dominated by powerful images and social media, style may often triumph over substance in politics.

"They look slick, but do they have the same amount of substance?" asks Kadri Liik, an Estonian political expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations think-tank.

"I sometimes fear what I call a 'davidcameronisation' of Estonian politics: politicians who look good, speak well, mean well, but lack true seriousness," she told the BBC.

She deplored a "tendency to believe that life is all about PR [public relations], performance, speeches and party politics".

David Cameron's defeat in the UK's 2016 Brexit referendum was a PR disaster - for a man who had been a PR professional before rising to the top of British politics.

Media-savvy and sporty

Wunderwuzzi's smart casual image showed he had a shrewd sense that young Austrians were yearning for political change.

Matteo Renzi (L) sported a leather jacket, enhancing his youthful image

A penchant for open collars and swept-back hair conveyed a boyish image - not like the decades-old stereotype of Austrian coalition wheeling and dealing by men in grey suits.

Smart casual was also the look of Matteo Renzi. His pose in a white T-shirt and leather jacket led The Guardian to ask, external if Mr Renzi was modelling himself on "The Fonz", star of the US hit sitcom Happy Days.

Sophie Gaston, deputy director of the British think-tank Demos, says this new breed of political leaders "share an understanding of the modern forces at play in campaigning - particularly their grasp of digital and social media - and how to harness these to connect directly with voters".

"This sets them apart from 'traditional' political elites in mainstream parties."

Mr Kurz, Mr Macron and Mr Renzi all rose through established party structures, but managed to convince voters that they were a breath of fresh air, intent on serious reform.

In that respect, Ms Gaston told the BBC, they have connected with many voters' rejection of the political establishment, especially since the 2008 financial crash.

"They are either seen as untainted by affiliation to this political hegemony or, as in the case of Macron, willing to take risks and challenge political orthodoxy."

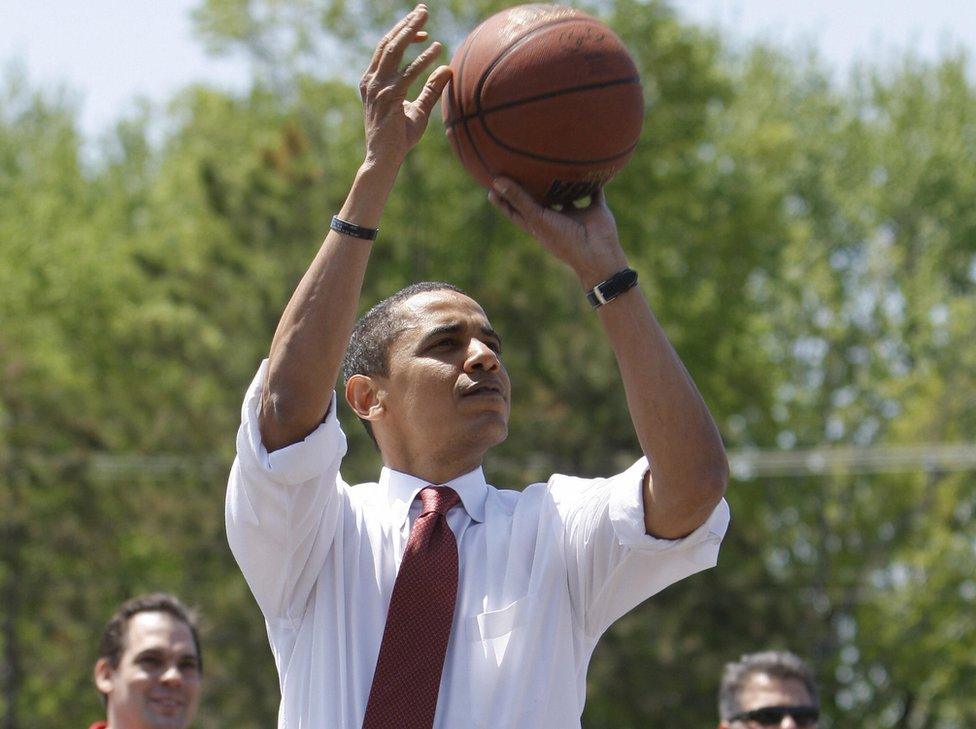

Barack Obama projected a sporty image early on - even before becoming president

Their communication skills enabled them to outmanoeuvre far-right and far-left populist parties which, Ms Gaston said, were quick to exploit social media.

Indeed, the far-right Freedom Party in Austria accuses Mr Kurz of stealing its thunder on immigration controls.

Projecting a fit and healthy image is a feature of these leaders' success.

On the presidential campaign trail in 2008 Barack Obama played basketball in a photo opportunity in Indiana.

And as president he was often seen on the golf course - now something of a cliché for US presidents.

President Macron played wheelchair tennis in June - another memorable photo opportunity.

Many leaders today have been photographed jogging, including Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, a youthful 45.

But Robyn Urback of Canadian national broadcaster CBC complained, external "we keep falling for Trudeau's PR".

It was no accident, she wrote, that his personal photographer snapped him jogging past "a group of kids taking pictures on the boardwalk". It made for a nice "feel good" picture.

Mr Macron also has a keen eye for image management. Just before his official photo shoot in the Elysee Palace he was filmed obsessively leafing through a book to find just the right page, so that it could be shown open and impressive on his desk.

Behind the scenes: Mr Macron takes care of the little things...

New rhetoric

We are living in a time of "general dissatisfaction with the status quo of politics", says Prof Catherine de Vries, a European politics expert at Essex University.

For decades, she told the BBC, ambitious politicians had to work their way up the party ranks - but that is no longer the case.

They do, however, need "extreme drive - it's not a nine-to-five job". Youth is an asset, she said, along with vision and a will to change the system.

Matteo Renzi was known as Il Rottamatore ("The Scrapper") because he fought the centre-left Democratic Party establishment. "I didn't want to submit to their rules," he said.

Mr Macron abandoned the Socialists when he realised he could woo a vast number of discontented voters outside the party.

But his popularity has slumped in recent months.

So the acid test of the new leaders is whether they can walk the walk, as well as talk the talk.