Andrej Babis: The populist billionaire who could lead the Czech Republic

- Published

Andrej Babis's centrist, anti-establishment ANO movement leads the polls

Voters in the Czech Republic are likely to hand power to controversial billionaire Andrej Babis, the country's second-richest man who ran on an anti-corruption platform but is himself under investigation.

The campaign has been dominated by big themes including euro adoption, immigration and the relationship with Russia, but also some more obscure ones, such as the rising price of butter.

Antonin Kokes is a burly, bearded man in his late 40s, with intense eyes and a ready smile on his lips. And he has a lot to smile about. After making a fortune in the board game business, he's been able to concentrate on his lifelong passion: bread.

Not that he bakes it himself, or even considers himself much of a cook. But he's just opened the fourth in a chain of bakeries bearing his name. The first, just off Prague's trendy Jiriho z Podebrad square, is buzzing with activity when we sit down for coffee.

"We started four years ago. I missed good bread in Prague," Mr Kokes said.

"I was travelling a lot in Germany, Switzerland, France. And I saw little bakeries where fresh bread is baked right on the spot every day with a nice friendly atmosphere, and I thought - OK, let's create it here."

"We're at a crossroads," says Antonin Kokes

He laughs when I ask whether the high butter prices are hurting his business - each bakery goes through 100kg of the stuff per day.

"I'm surprised this is such a big issue to be honest. I don't really get what all the fuss is about," he says.

Mr Kokes's sunny disposition darkens when I ask about Andrej Babis. As finance minister he promised to cut red tape, making the Czech Republic an easier place for entrepreneurs like Mr Kokes to do business.

"When I first met and heard Babis, I thought - he is one of us. He will help small businesses. But the things that are happening are quite the opposite," he tells me, explaining that a centrally-monitored online sales register plus compulsory monthly VAT controls are hampering, not helping Czech companies.

"The state hasn't diminished. It's grown."

Mr Babis - who promises to run the country like a business - says his innovations have helped raise taxes and whip Czech public finances into shape; the economy is now in surplus, living standards are rising.

His own finances, however, are far murkier. As well as his sprawling agrochemical empire, he owns the country's two leading daily newspapers and a radio station. But it was his Stork's Nest farm and conference centre that brought his career as finance minister to an end, after he was formally charged with fraudulently obtaining EU funds for the facility.

His parliamentary immunity lifted, Andrej Babis - whose fortune is estimated by Forbes, external to be worth $4.1bn (£3.1bn) - now faces two separate investigations by the Czech police and the EU's anti-fraud unit.

Neither his spokeswoman nor half a dozen MPs in his ANO party responded to requests for an interview. But Mr Babis - prickly, plain-speaking - has aggressively dismissed the claims as part of a co-ordinated campaign by his rivals in the political establishment.

And he still has his sights set on high office.

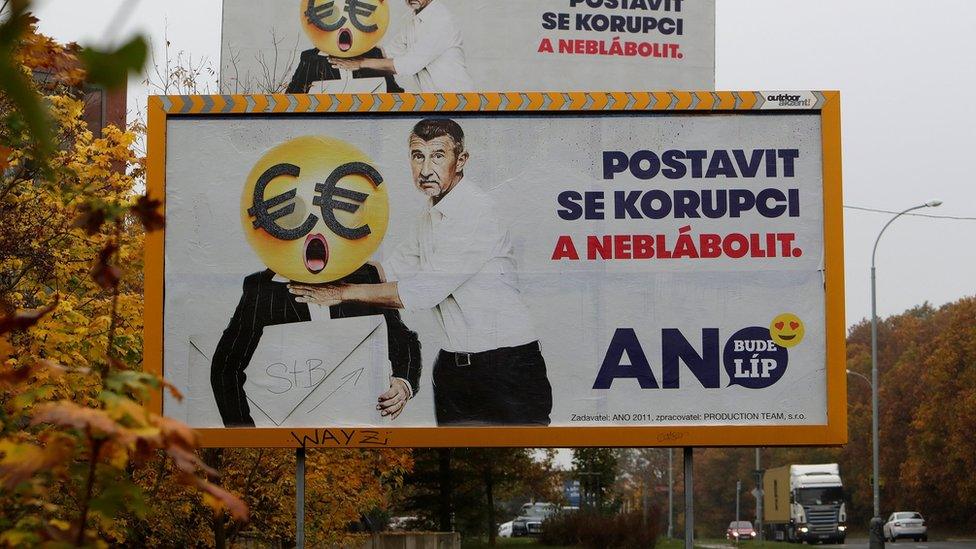

Stand up against corruption, urged his poster by Mr Babis, himself under investigation

"Look, there are very few Czech politicians who are as hard-working, as assertive, as good a manager as he is," said Pavel Telicka, who was an MEP for the ANO party until he broke with Mr Babis a week before the election, chiefly over foreign policy.

"There are not that many Czech politicians who speak the languages he speaks. There are not many people who would have [German finance minister Wolfgang] Schauble or [French president Emmanuel] Macron in his cell phone," Mr Telicka told the BBC.

"The question of course is what is the direction in which he would steer the government as prime minister. And that for me, after the experience of the last few months and the disagreements we've had, well, that's a question mark."

Others, too, are unsettled by Mr Babis's positions. Unlike Pavel Telicka, for example, he is opposed to euro adoption. He is firmly against EU quotas of refugees and hostile to Muslim migrants. But those stances are virtually mandatory these days for Czech politicians; to be otherwise would be remarkable.

Mr Babis has promised to run the country as a business

On other issues, like relations with Russia, what Mr Babis thinks is less clear.

"Babis is not the Kremlin's guy," said Ondrej Kundra, who's written extensively on Babis for the liberal Czech weekly Respekt.

"On the other hand, he's also not very pro-EU. He is somewhere in between," added Mr Kundra.

"Until now, we are the only country within Central Europe which doesn't have a real populist party in government. Of course, that could change if Babis forms a coalition with [the far-right] SPD or the Communists. Then - yes - we can turn the Hungarian way."

Back at the bakery, Antonin Kokes is also worried about that sense of drift, away from Europe, away from euro-Atlanticism, away from liberal democracy.

"I think we are at a crossroads. The world is changing. And I think Czechs will have to decide if we want to be part of the EU, or maybe we will go another direction," Antonin told me.

"Yes, this direction could be 'Russia'. But it could also be a direction called 'nowhere'. This is the question."

- Published20 October 2017

- Published11 December 2023