Albania: The country searching for hundreds of mass graves

- Published

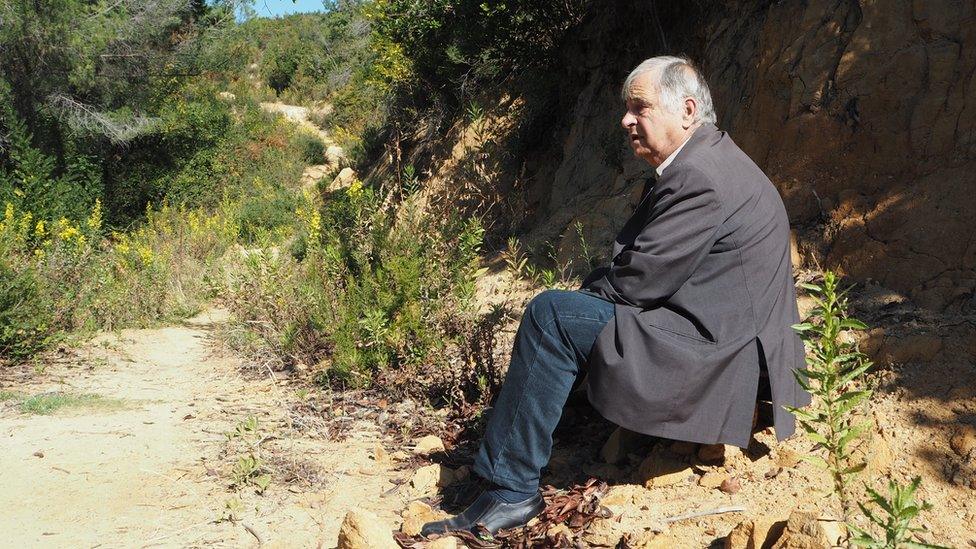

Nikolin Kurti at the site of the mass grave he uncovered in 2009

A generation after the fall of its Communist dictatorship, Albania is starting to uncover evidence of thousands of people executed by the former regime.

More than 30 years after his death, the country is beginning to come to terms with the terrible legacy left by the Communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. And it was ordinary people who began the search for the truth about the labour camps, mass graves and secret police which characterised those times.

"Please don't ask me how difficult this was. I can't even begin to tell you how difficult it was. We were just digging out bones and skulls, trying to piece things together. It was very grim."

So says retired chemical engineer Nikolin Kurti, 68, who took us to the outskirts of the Albanian capital, Tirana, and then up Mount Dajti. It was here, now overgrown with bushes and brambles, that he had excavated a mass grave in 2010, uncovering the remains of 14 people.

Enver Hoxha ruled Albania for more than 40 years

"It all started when a policeman told me that my uncle was buried here," he explained. That uncle, a Catholic priest called Father Stephen Kurti, was executed in 1971 after he had been found guilty of secretly baptising a child.

Enver Hoxha had criminalised all forms of religion and Father Kurti paid the ultimate price for disobeying a totalitarian state that has often been compared to today's North Korea.

Now Albania itself has begun the difficult journey into its own tragic past that may result in the search for possibly hundreds of mass graves.

Albania's troubled past

1939 Italy invades. Albania's King Zog flees

1944 Following German occupation, Communist Enver Hoxha becomes leader

1946 Non-Communists purged from government positions. Regime will outlaw religion, murder political opponents and run labour camps

1961-78 After breaking with the USSR, Albania allies with China

1985 Hoxha dies, replaced by Ramiz Alia

1989 Communist rule in Eastern Europe collapses. Ramiz Alia signals changes to economic system

1991 First multiparty elections

Enver Hoxha's was one of the most brutal and paranoid of Communist regimes. An estimated 200,000 people passed through the labour camps that were modelled on Stalin's Gulag. More than 6,000 went missing. Now thousands of their relatives and friends want to know what happened to them.

Nearly all the missing people are believed to have been executed or died of neglect or torture in the camps. Many were political prisoners, suspected of opposition to the regime.

Recently, Albania's socialist government has entered negotiations about the possibility of locating and possibly opening mass graves.

Some mass graves are likely to be located near the work camps, including the particularly notorious Spac prison in northern Albania.

Etleva Demollari, director of the House of Leaves, with Sigurimi gadgets

In September, Albania's Prime Minister Edi Rama met Kathryne Bomberger, director general of the International Commission for Missing Persons. The ICMP is an intergovernmental body that works with governments on the issue of missing persons.

It has helped to discover mass graves elsewhere in the Balkans, resulting mainly from the wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. The organisation also provides the DNA testing needed to identify remains.

The government and the ICMP have discussed the next steps in establishing a programme to help locate missing people. The initial phase will concentrate on the remains discovered by Nikolin Kurti on Mount Dajti and at another site in Ballsh in southern Albania.

Matthew Holliday, head of the ICMP for the Western Balkans programme, said it was important for relatives to establish both the fate and the location of missing persons.

He said: "The issue of the missing is not about the dead; it is about the living. These are families that have a right to know. They need to know the fate of their missing relatives, and to have received the remains, to have them identified and to give them a dignified burial."

Gentjana Sula with some of the Sigurimi files

And the country's quest to come to terms with its past has manifested itself in other ways, too.

In recent months, Albania has opened as a museum the so-called House of Leaves, in the old headquarters of Hoxha's much feared secret police, the Sigurimi. It has also opened up the Sigurimi's files.

Gentjana Sula, the head of the newly created Authority on Access to Information on Sigurimi files, said: "I think the interest is high and, according to our research, about 70% of people want to know and see a benefit of knowing more of the files. The right to truth has been denied for all these years."

Ambassador Bernd Borchardt, head of presence in Albania for the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, welcomed the opening of the files, adding: "Knowledge is the basis for liberalising narrative, for the reconstitution of a nation's memory.

"It played an important role in Germany where fortunately the files were captured by civil society at an early stage. Here it took much longer, but now the government and the parliament have decided to open these files."

Nikolin Kurti asked for DNA tests to be carried out on remains he was convinced belonged to his uncle. Sadly the tests proved negative. His search for the final resting place of Father Kurti goes on.

- Published28 June 2023