Romania's King Michael: A democrat in the face of totalitarian regimes

- Published

King Michael spent most of his life living in exile

Michael of Romania was a king without a throne at the end of World War Two.

He had already spent seven years as sovereign: first as a child, when his father Carol II renounced the throne in 1927, only to return three years later.

At the age of 18, King Michael became monarch for a second time in 1940, after his father was forced to abdicate as Romania sided with Nazi Germany in the war.

Fighting back

Michael, who did not come of age until his 21st birthday in 1942, was treated with contempt by Romania's fascist dictator Ion Antonescu during the four-year alliance with Hitler.

So it must have come as a surprise when the 22-year-old king - up until then, little more than a figurehead - became involved in a coup against the dictator and ordered Antonescu's arrest on 23 August 1944.

As a result, Romania severed ties with the Nazis and joined the Allies - only to find itself under Red Army occupation and sliding inexorably towards a communist takeover.

By the end of 1947, King Michael was the last obstacle between Stalin achieving absolute political control through his communist agents in Romania.

The king, seen here in 1951, had five daughters with his wife Anne

He was finally forced to abdicate on 30 December, 1947.

Sitting at home in Switzerland more than four decades later, he would tell me how then-Prime Minister Petru Groza showed his mother, Queen Elena, the pistol on his belt as Michael signed his abdication.

Groza's reasons were clear: "I don't want to have the same fate as Antonescu," was his explanation to the king.

The prime minister was only half joking. The building may have been surrounded by troops loyal to the communists, but the king was still very popular among Romanians.

He was forced into exile four days later, his political activities forbidden. On another occasion, this time in London, King Michael would tell me how he had been seen off at the railway station by the whole communist-led cabinet, who were radiant with the hope that he would never return.

He was very courteous and, although formal, he was never distant or haughty. King Michael had a speech impediment, which meant he was not a great speaker. And yet he was always well informed.

He may not have been an intellectual, but in the five times I interviewed him he always expressed ideas in a clear and dispassionate way. He came across as a great Romanian patriot.

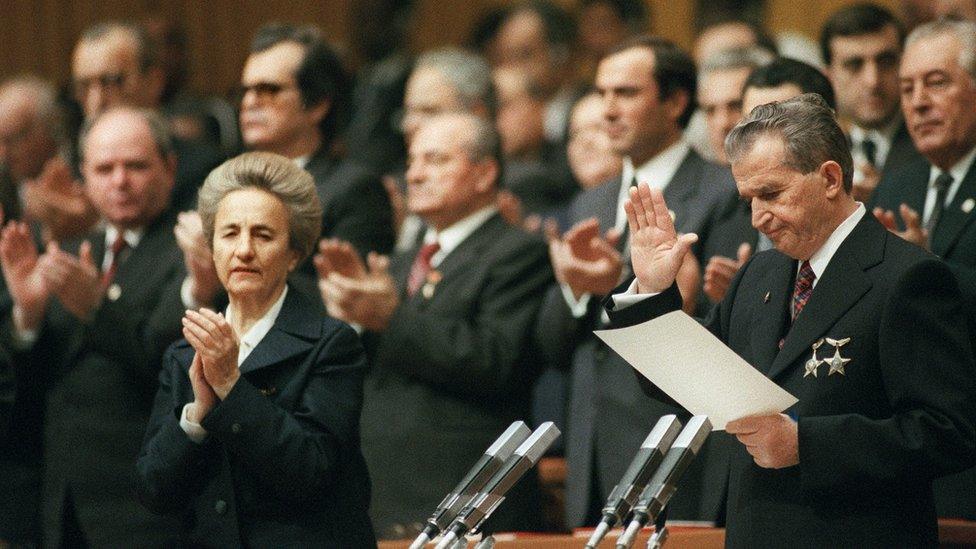

Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu (R) was hostile to King Michael

In the UK it was made clear to King Michael he could not expect any support from the West.

All the same, he vowed to return to Romania, driven by a sense of duty, instilled in him largely by his mother.

But Michael did not go back until 1990, with the fall of dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. Even then he was given only a lukewarm welcome from post-communist governments, nervous about their legitimacy.

He addressed Parliament in 2011, accompanied by his daughter Princess Margaret, to mark his 90th birthday

It was only in 1997 that he was fully accepted in his homeland, when Romania became a candidate for the European Union and Nato.

King Michael, descended from Queen Victoria on both sides, had connections with many of Europe's other royal families, and was seen as useful.

At the end of his life, King Michael may not have quite retained his earlier popularity, but he was still treated like an elder statesman as he faded from public eye due to his failing health.

His wife Anne, who he met at the wedding of Britain's then Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip in 1947, was buried with state honours in 2016, despite never having been crowned.

Other members of Michael's family have taken up an ever more prominent place in Romanian public life, even though critics argue they were never "royal" in a true sense and lived off the king's longstanding reputation.

For Romanians, Michael was an important player throughout some of the most difficult times in their history: at heart a decent man and a democrat in an age dominated by totalitarian regimes.

- Published25 October 2011

- Published13 August 2016

- Published16 March 2015

- Published18 December 2024