How Britain pioneered cable-cutting in World War One

- Published

The UK's most senior military officer has warned of a new threat posed by Russia to communications and internet cables that run under the sea.

But the reality is that an understanding of this threat is anything but new. And it is the UK which first pioneered the technique of cable-cutting just over a century ago.

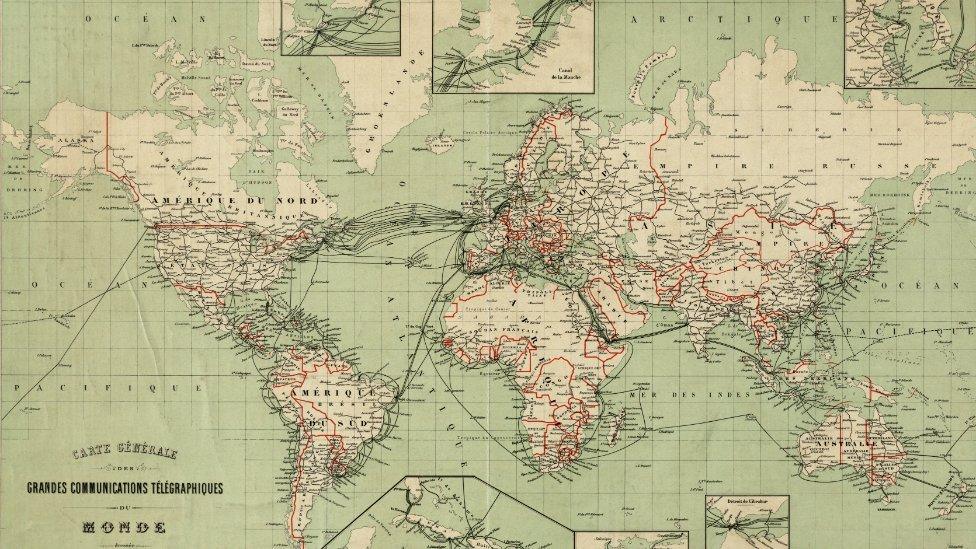

At the outbreak of World War One, Britain had the most advanced undersea telegraph cable system. It wrapped around the world, due to the reach of the British Empire. The dominant position offered an opportunity and strategists were determined to make the most of it. But first, German cables had to be dealt with.

A telegram arrived at the port of Dover just past midnight on 5 August 1914, the day after Britain declared war on Germany. It was in code, so its meaning would have been lost on anyone apart from its intended recipient, an officer named Superintendent Bourdeaux.

Britain dominated much of the world's undersea cable network in 1914

"We were taking a considerable risk," Bourdeaux recounted in his report. At 01:52 he was on board a ship, the Alert, as it set sail. The bulk of the crew didn't know what their mission involved as the Alert arrived at its first destination at 03:15, lowered its hook to the seabed and began to dredge.

Bourdeaux and the Alert were undertaking one of the first strategic acts of information warfare in the modern world. A few hours later, the Alert had cut off almost all of Germany's communications with the outside world. It had hit the kill switch.

Russia a 'risk' to undersea cables, defence chief warns

Could Russia cut undersea communication cables?

Why was the Zimmermann Telegram so important?

BBC - World War One At Home, Porthcurno, Cornwall: Cable Wars

Cutting German cables was originally seen as primarily a way of denying the enemy the ability to communicate. But it soon became clear it also offered intelligence possibilities as well.

On 4 August, just before the Alert set sail, a man arrived at the cable station at Porthcurno in Cornwall. On the secluded beach, telegraph cables carrying traffic across the Atlantic came ashore.

The job title of the man was a "censor". In the office of the Eastern Telegraph Company in the British colony of Hong Kong, another "secret censor" walked into his new office.

A similar figure did the same in every far-flung corner of the British Empire, from Malta to Singapore. Once the censors were in position, instructions had told them to send a message to London reading "Fixity London, Fixed".

Britain cut German telegraph cables in August 1914 but also intercepted its communications during World War One

A global system of interception had been instituted. Known as "censorship", its aim was "to prevent intelligence being conveyed to the enemy and to cut off the enemy's correspondence with his agents".

Britain was taking advantage of its dominance of the international telegraph infrastructure to create the first global communications surveillance system, from Cairo to Cape Town, from Gibraltar to Zanzibar.

Fifty thousand messages would pass through the hands of 180 censors at UK offices alone every single day. Another 400 worked in 120 stations overseas. In all, 80 million messages would be subject to censorship during the war.

The combination of cutting German cables and forcing communications on to British lines provided an intelligence windfall.

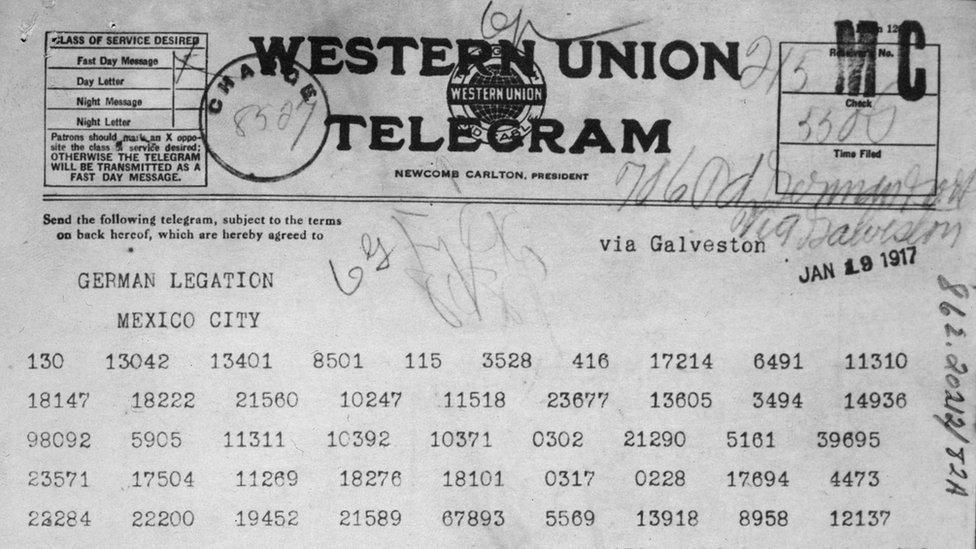

Among the messages that Britain intercepted in World War One was the so-called Zimmermann Telegram which revealed a German plan to offer US territory to Mexico and which, in turn, was used to help draw the US on to Britain's side in the war.

Cable-tapping continued through the Cold War. America's Central Intelligence Agency and National Security Agency (NSA) had an operation codenamed Ivy Bells to tap into Soviet military cables but it was exposed by a traitor.

The Zimmermann telegram, intercepted by the British, helped draw the US into World War One

And today cables still matter. In January 2002, a storm battered Porthcurno in Cornwall. In the aftermath, strips of thick, black wire were exposed on the beach like fossils.

These were fragments of disused telegraph cable as well as the skeletons of their predecessors, two modern cables pulsing with life were also unearthed by the wind and rain. These were fibre-optic cables bearing beams of light which carry the ones and zeros that connect together the modern world.

The routes these cables were laid on were often similar to that of the Imperial telegraph system.

One of the things Edward Snowden, the former CIA employee and NSA contractor who leaked to the media details of extensive internet and phone surveillance by various intelligence services, revealed was the way in which Britain's GCHQ and America's NSA had been able to tap into these cables in order to scan and filter global telecoms traffic to gather intelligence on their targets.

But as well as intelligence gathering, there remains the fear that countries could hit the kill switch once again and cut off traffic.

In reality, this would probably only be done - as in August 1914 - in the event of war breaking out. But because of the world's dependence on digital communications - the consequences today would be far more serious than when the Alert set sail.