Catalan political landscape as divided as ever

- Published

Pro-independence parties can one again form a majority in parliament

The voters of Catalonia went to the polls for the fourth time in four years on Thursday and once again produced a result which demonstrates how deeply divided their society has become.

The result provoked an outpouring of joyous relief from supporters of parties who want independence from Spain.

They just about hung on to their narrow overall majority in the parliament although the number of seats under their control fell from 72 to 70.

They say this was a victory won under duress.

The leader of one separatist party, Oriol Junqueras, was in solitary confinement in a Spanish prison when he was re-elected.

The head of another - the deposed former Catalan President Carles Puigdemont - was in self-imposed exile political in Brussels from where he told his supporters: "The Spanish state has been defeated, the independence movement has won. This is a majority that wants a referendum."

But Catalonia's political landscape remains crowded and complicated and it is hard to see a way forward through it.

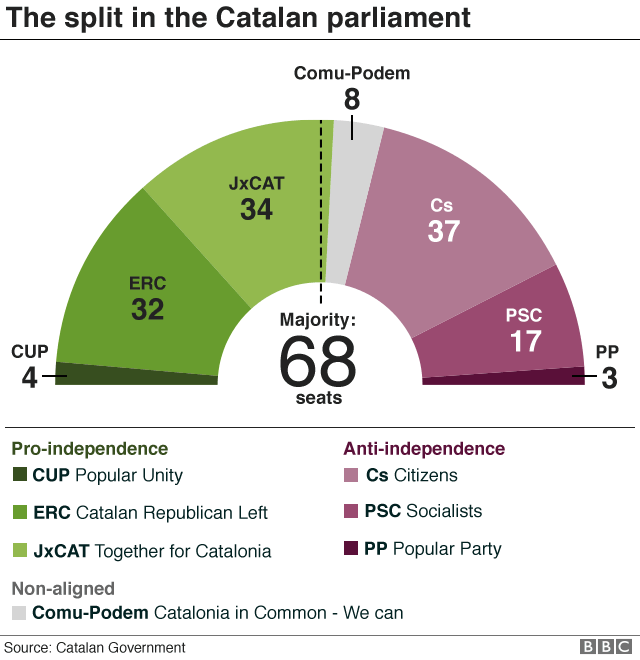

Seven parties will be represented in the new parliament, none of them with more than a quarter of the overall vote.

The largest of them, Ciudadanos (Citizens), is a unionist movement - in other words it's as determined to keep Catalonia's links with Spain as its rivals are to break them.

The party leader, Inés Arrimadas, said: "We'll see how a coalition can be formed. We have a very unjust law in Catalonia so that the pro-independence parties can have a majority (in parliament) that they don't have on the street."

Unionists argue that the voting system is biased against them because the pro-independence parties have strong support in small towns and in villages, where it takes fewer votes to win a seat than it does in Barcelona, where a majority favours staying with Spain.

But the reality is it's very hard to see how Ms Arrimadas has any realistic chance of forming a government when the numbers are stacked against her - however narrowly.

Inés Arrimadas's Citizens party won the biggest number of seats but will struggle to form a government

At the party's "victory" rally in the centre of Barcelona, one of her supporters, Natalia Ferrer told me she thought Ciudadanos had done well enough to make it impossible for its rivals to push for immediate independence.

As she put it: "I am so happy that we have shown to the rest of Europe and the rest of the world that not everyone in Catalonia is against Spain... there are a lot of people here who want to be part of Spain."

And there, of course, is the problem.

One lesson from Thursday's election is that if you keep asking the same people more or less the same question then you'll keep getting, more or less, the same answer.

And here is a further layer of complexity, in case this didn't seem complicated enough.

The real loser in this latest Catalonian election was a man who wasn't even standing, the Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy.

He is an unwavering opponent of the separatist movement and it was his decision to impose direct rule from Madrid after October's illegal referendum.

Spain has an independent judiciary, of course, but it's also on Mr Rajoy's watch that opposition leaders from Catalonia have been sent to prison - and could yet face 30-year jail sentences for rebellion and sedition.

A look at the key players in Catalonia's regional election

It was Mariano Rajoy's decision to call these latest elections and it seems clear that he was gambling that the constitutional crisis of the past few months would have eroded the support for independence.

That gamble has failed and now he has to decide how to deal with jailed or exiled leaders who have demonstrated again that they have a popular mandate.

He is the man who would presumably have claimed a share of the victory if unionists here had won and on that basis, his is the defeat.

- Published14 October 2019

- Published20 December 2017

- Published18 October 2019